Normally, the Chico News & Review publishes a special Local Heroes issue to coincide with the Thanksgiving holiday, when we give thanks to those who volunteer their time for our community.

This is not a normal year.

During a pandemic, the frame of reference for what makes a hero shifts. Suddenly, it becomes obvious that the person bagging your groceries or filling your prescription does essential work—and that their continuing to clock in, despite the risks, is critical and heroic.

We decided to save recognition of community heroes—most of whom represent a larger group doing the same work—for the final issue this year, to end 2020 on a positive note. In another break from tradition during these unique times, we’ve removed the volunteer requirement to open up the honor to anyone who’s helped, sacrificed or otherwise stepped up this year.

(Read our readers’ picks here: “Your heroes“)

In harm’s way

When someone refers to Dr. Steven Zlotowski and his colleagues in emergency medicine as heroes for what they’ve faced during the pandemic, he takes the compliment with a dose of self-awareness.

“I sometimes say, ‘We might be trying to do something that’s heroic, but I don’t know that we’re heroes,’ because I don’t believe that we are,” he said. “That comes from the fact that we’ve been showing up and doing our job just like this, under challenging circumstances, whatever anybody throws at you, whatever holes in the safety net there are in society—we’ve been doing this our whole career. We know what we signed up for; we understood about pandemics and infectious diseases when we got into this business.

“So this is another flavor of ‘business as usual’ for us.”

Still, COVID-19 has shaken even the most unflappable physicians at times. The pandemic’s onset overwhelmed hospitals in several large cities, most notably New York. From Chico, where he works at Enloe Medical Center, Zlotowski made a video plea—which went viral—for people to take precautions seriously.

While bracing for a winter surge, Zlotowski said medical professionals find themselves in different circumstances now than six months ago. In March, providers lacked experience diagnosing this new coronavirus, testing wasn’t widely available and facilities faced shortages of personal protective equipment—“so you were basically flying blind at very high speeds without a parachute.” Testing capacity has expanded, though “still not to the capability or the turnaround time we would like it,” and he said the hospital “has done a phenomenal job at getting us PPE, so we’re comfortable we have the protection that we need.”

Back in March, Zlotowski assumed he would contract COVID-19 at some point. Though relatively young (he just turned 58) and in good health, he—like other frontline health workers—gets exposed to the virus far more than the average person.

“But I don’t fear for my life, even though I acknowledge I could be at risk,” Zlotowski said, drawing on an Irish saying his “second mother” used to tell him. “You just swallow the heartache … instead of having something that’s painful poke and prod you every day for some period of time, you just swallow it one time. I think I probably took from her wisdom in March.

“That said,” he added, “I’m taking all the precautions because it matters more than just to my own personal health whether I get it.”

—Evan Tuchinsky

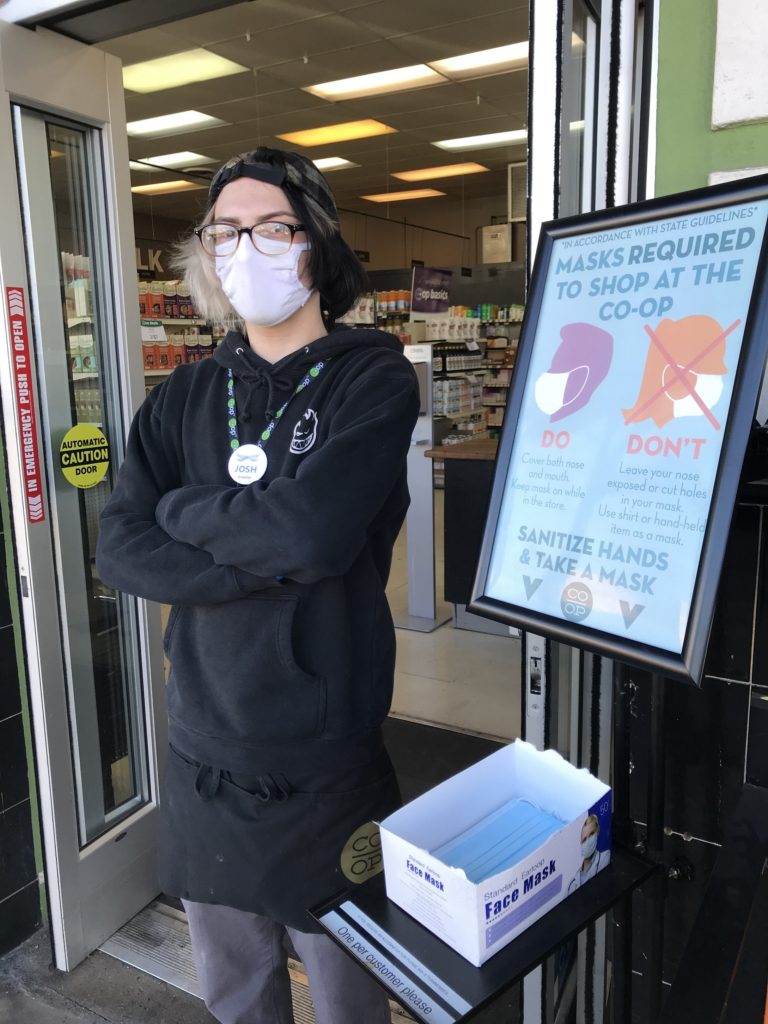

Store sentries

In summertime, as wearing facial coverings in public places shifted from recommended to required in California, social media feeds choked with videos of bad behavior sparked by the enforcement of so-called mask mandates.

Chico had its own dubious Internet star in a woman dubbed “Panera Patty” by some (and “Farty Farrah” by others). In July, she was caught on film at the local Panera Bread refusing requests from employees and other customers to don a mask provided by the restaurant—then blowing on other customers and offering questionable proof about the inefficacy of masks based on the ability to detect flatulence.

As most retail and grocery workers can attest, every viral video likely represented thousands of unfilmed confrontations. All the workers put their own health at risk to keep essential businesses running, but especially those “store sentries” who’ve stood steadfast in the proverbial trenches in a battle of proven data and public health information versus pseudoscience and perceived threats to personal liberty.

Usually, these are front-end workers who never signed on to engage in conflict, let alone enforce controversial public health rules.

At Chico Natural Foods Cooperative (CNFC), employees began wearing masks just weeks into the pandemic—at first suggesting customers do so as well, then requiring them to once the state mandated face coverings in public buildings on June 18.

The CNFC sentry position first fell on management, who took shifts at the front of the store during what was correctly anticipated to be a difficult transitional period. Brand Manager Joey Haney confirmed that confrontations ensued; in the worst episode, police had to be called after a mask-denier shouted racial slurs, threw a brick of cheese against the wall and blocked the store’s doorway.

In July, the store hired Josh Girard to work specifically as a greeter. “I assumed there’d be some combativeness, but I didn’t expect it to happen as frequently or for people to be so difficult,” he said. Haney and Girard said the tantrums have largely subsided, but still happen.

—Ken Smith

Standing up for the stigmatized

Though impacts of the coronavirus may have affected people most acutely in 2020, longstanding issues continue to weigh on communities locally and nationwide. Discrimination—notably, violence by police against people of color—and homelessness attracted mass attention, with people taking to the streets to protest George Floyd’s killing as those living on the streets faced intensifying scrutiny.

Concerned citizens put themselves at the nexus of these problems; locally, few moreso than Marin Hambley, who in just three years in Chico has become a tireless champion for underserved, underrepresented and stigmatized individuals.

Hambley works as advocacy and education coordinator for Stonewall Alliance Center, hub of Chico’s LGBTQ community, which this summer established a grant fund for queer and trans people of color. They’re also operations leader for the Safe Space Winter Shelter organization through which they, with Siana Sonoquie, manage Project Roomkey—the state-funded program that provides motel rooms for at-risk homeless people and low-income COVID-positive patients who need to quarantine. In addition, Hambley volunteers as outreach lead for the North Valley Harm Reduction Coalition, which despite suspending syringe distribution still provides free public health services.

“There’s a lot of areas of discrimination and stigma,” Hambley said. “There’s a merging of all three of my jobs in a lot of ways.”

Hambley didn’t start out in social service. When they came to Chico, a 2016 graduate of UC Davis, Hambley was a groundskeeper. Working the landscape at Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. on the morning of the Camp Fire changed their perspective, and Hambley left that position to start helping the thousands displaced by the disaster.

“There were different forms of connections made with people organizing and fleeing, and the overlap of those two categories,” Hambley said. “I really got entrenched in a lot of community work…. I am nothing without the people around me, and I started building on those relationships and those connections of care and vulnerability as more disasters kept happening.”

Including our current one.

“Current multiple ones,” Hambley corrected.

—Evan Tuchinsky

Angels of the encampments

Dedicating time and energy towards helping the most vulnerable members of our community—the unhoused—is always a noble effort. Doing so during a pandemic is downright heroic.

The outbreak of COVID resulted in Chico City Council relaxing rules against public camping in early April, causing numerous encampments to spring up in parks and near waterways. This effort to comply with the U.S Centers for Disease Control and Protection’s guidelines has been a political hot potato since the camps appeared, adding fuel to already raging debate over how to deal with homeless issues and standing as a major concern in this year’s City Council elections.

As soon as the encampments arose, helpers in the community stepped up to lend a hand. The earliest outreach efforts were organized by the Democratic Socialists of America’s local chapter and focused on education.

“The DSA’s Mutual Aid outreach basically started with me and [local homeless advocate] Bill Mash going out to the encampments with snacks and hand sanitizer,” said Addison Winslow, who helped coordinate volunteer efforts. “We kind of used the hand sanitizer as part of our schtick to start talking to people about COVID. We told them about flattening the curve and helped people who asked us, ‘Is this real?’ understand that it is.

Those outreach efforts expanded rapidly, with funding from the state’s Project Roomkey initiative allowing for meals prepared by Chico Unified School District to be delivered by dozens of volunteers daily for the first two months of the crisis. The bulk of that and other regular outreach work was carried out by unpaid volunteers, including some affiliated with Safe Space Winter Shelter, True North Housing Alliance and other local service providers. Other outreach efforts included weekly trash removal and cold water dispensed during the summer months.

Organized outreach efforts have dwindled as time passed and funding to help pay for food and water was exhausted, but the DSA recently began a Cold Weather Mutual Aid program (DSAChico.com) and Safe Space is collecting monetary donations (safespace

chico.com), with both efforts aimed at delivering necessities to the unhoused.

And, at least one volunteer who’s been involved since the early days of encampment outreach has never stopped. Sawyere Lamontagne, a Chico State social work student who participated in the DSA’s first efforts, continues to visit the camps every Sunday of his own accord, delivering donated food to those living outside.

—Ken Smith

Mask makers

When Idea Fab Labs (IFL) opened in 2012, Erin Banwell envisioned artists and crafters using the Chico maker space to create unique works. He didn’t see it as a factory.

Then came 2020, year of the pivot. State public health orders forced the makers to stay home, idling his equipment. Meanwhile, medical facilities and public agencies scrambled to provide frontline workers with face coverings and other protective gear as the pandemic caused global shortages.

A phone call from Banwell to Butte County Supervisor Debra Lucero connected the dots. Funded by a grant from the North Valley Community Foundation, IFL made 3,500 fabric masks for In-Home Supportive Services’ caregivers. Thus started a venture that, at its peak, employed 27 and filled orders as large as 40,000 for masks and faceshields.

“This was really a complete pivot, into producing PPE,” Banwell said. “We had all the appropriate tools; it was really about filling the need—and also keeping our doors open, because our main business model fell completely flat. … We completely retooled for this need.”

Initially, for the fabric masks, IFL pieced out the sewing to people in their homes. Managing the work of 100 freelancers proved challenging—Banwell has run a mostly one-man shop on Orange Street, with partner Jordan Layman heading their Santa Cruz spinoff—so he now contracts with Diest Co. Manufacturing for sewing at that facility by Chico Municipal Airport.

Perhaps the most stressful moment came courtesy of the faces shields. IFL started making those from clear polycarbonate material at the request from Enloe Medical Center. Banwell had delivered the initial batch from an order of 1,200 when he got a late-night call saying the head nurse for infectious diseases had determined the shields were 2 inches too narrow and, without more, the hospital would run out of this protective gear the next day.

“That was a crazy moment for me,” Banwell recalled. He rushed to work, changed the design, and his crew made the new ones fast enough that “we got them a batch of several hundred that next day.”

IFL, with another NVCF grant, also made 10,000 face shields for distribution by the health departments of five North State counties, including Butte.

Demand for locally made PPE has slowed now that large-scale manufacturers have caught up; factories in China can produce units more inexpensively. Same for the basic fabric mask, but IFL has carved a spot in the niche market for custom and fashion masks. At a special site (iflmasks.com), people can order designs from artists, who get commissions for use of their work, and businesses or organizations can get masks with their logos on them.

—Evan Tuchinsky

The show’s still on

Public entertainment venues were the first to close and will be the last to reopen during the coronavirus pandemic. That, of course, is bad news for businesses who make their livings producing live shows as well as for the artists who perform them.

In addition to the financial impact COVID closures have had on Butte County’s entertainment industry, there’s also the spiritual impact on isolated residents deprived of experiencing art and public performances in person. Beyond distanced musical accompaniments to dinner and drinks at local restaurants, or drive-in style theater events, the only option for “live” events has been virtual.

Of the handful of local artists who’ve been able to harness the resources and the technology to present themselves online, none has delivered the much-needed connection to the performing arts so completely as electro-pop duo Astronaut Ice Cream.

“We had this big tour booked for April,” guitarist Kirt Lind said about the band’s pre-coronavirus plans. “And when that got canceled, immediately I was like, ‘I still want to do this show.’”

So they did. With the help of band videographer Joey Moshiri, on the evening of April 2, the duo staged a livestreamed concert from under a gazebo on a ranch in Capay. They followed up the show with a video for the song “Better Days,” a tune from the band’s then to-be-released album Blue, for which they’d end up making and releasing a video for every track—nine total.

“The whole rest of the summer, we’d finish one video and start the next,” Lind said.

“Even if COVID wasn’t over, we knew it was going to be awhile before we got to perform, so the videos became performances for us,” vocalist Heather Marie Ellison added.

Besides sharing videos online, the band organized additional interactive livestream events, including an album-release listening party for Blue and a Halloween Eve variety show/chat featuring Astronaut Ice Cream live with prerecorded performances other local performers—including spooky rockers WRVNG, and cocktails and comedy with local thespians Betty Burns and Delisa Freistadt.

“Halloween was really special this year, and I don’t think a lot of people can say that,” Ellison said about the interactive experience.

“At first it seemed like this was the replacement,” Lind said about the band’s forced shift online, adding, “I’m pleasantly surprised at how much fun we had doing it this way.”

—Jason Cassidy

T-shirts off their backs

When the statewide stay-at-home order was announced in March, Silkshop Screen Printing co-founders Cameron Harry and Nick Johnson saw many of their favorite restaurants, bars, coffee shops and movie theaters close immediately and indefinitely. Their local print shop was temporarily closed, too.

“We saw the seriousness of the situation that we and all of these places that we love to go to were in,” Johnson said, “but the one thing that didn’t seem to get hurt was online stores. We thought if we could approach all these businesses, starting with the ones we’d worked with before, we could print shirts to raise money for them and keep our lights on at the same time.”

Print shops across the country had the same idea, and the fundraiser became a movement of sorts, on which each shop put its unique imprint. Silkshop’s version, Print Aid, generated $20,000 for the 60 local businesses that participated (including the CN&R) and sold more than 1,600 shirts in three months.

Johnson and Harry gave businesses $12 of each $20 shirt sale and put the rest into supplies and utilities.

The duo said they also enjoyed getting the chance to collaborate with the various designers and would be open to more fundraisers going forward.

“We’d definitely consider doing something similar. If there are certain places that can’t pay their own bills right now, we’re for sure down to help them out and set up a store,” Johnson said. “We also have to thank everyone who bought shirts, because they’re the ones actually donating the money.”

—Trevor Whitney

Advocate for action

One of the few positive things to be said about 2020 is that it has been marked by an increased awareness of and involvement in social justice issues. Months of Black Lives Matter demonstrations—sparked by the May killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police—have brought conversations about police violence and systemic racism to the forefront of national dialogue.

One of the many progressive-minded locals inspired to embrace direct action and hit the streets is Melys Bonifacio-Jerez. The Chico State sociology major said the desire to help people has always been close to their heart, but they were spurred to focus harder on those efforts this year.

Bonifacio-Jerez hails from New York City’s South Bronx but moved to this area in 2008 and started up at Chico State in spring 2019.

“[That semester] I took an ethnic studies class called Chicanx Literature,” said Bonifacio-Jerez, who is of mixed Dominican, black and Italian heritage and identifies as Afro-Latinx. “It was the first time I saw myself in a higher institution of learning, reading literature in Spanish, which was my first language. It made me feel really sane, and safe.”

Last fall, Bonifacio-Jerez became an intern with Students for Quality Education at Chico State, a group that aims to ensure accessible, affordable and equitable college education for all. This led to an introduction to and involvement with groups like the local Sunrise Movement and the Chico chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America.

Bonifacio-Jerez volunteered for the DSA’s mutual aid effort, shopping for groceries and delivering them to elderly and immunocompromised people in the early days of the coronavirus epidemic.

They attended most of the local BLM protests and helped organize the Chico Peoples’ Assembly, which held community meetings in Chico City Plaza to protest the city’s police budget and discuss how resources could be redirected toward positive community development. The Peoples’ Assembly maintains an Instagram page (@defundchicopd); Bonifacio-Jerez said they’d like to focus more on that effort in the next year.

Beyond that, they’re considering a future in politics.

“I have low-key aspirations to run for office someday,” Bonifacio-Jerez said. “It might be here, or maybe I’ll head to Sacramento to work on housing. I’ll be in some political realm, but am just trying to figure out where I fit in right now.”

—Ken Smith

For the greater good

In terms of collective impact on public health, the biggest heroes of the coronavirus pandemic might be those who have decided to follow the advice of health officials.

Businesses that have followed safety measures—or even closed their doors—and everyday people who stay home, keep physical distance and wear masks are doing critical work to slow the spread of the disease.

Without individuals choosing to make social—and oftentimes huge financial—sacrifices, COVID-19 would take many more lives. And though there has been, and will continue to be, huge economic fallout as a result (see “Treading Water,” page 8), the alternative would be greater human tolls and ultimate business closures.

The best way to show thanks is to stay vigilant ourselves and, when it’s all over, support the comebacks of businesses, organizations and anyone who took one for the team.

—Jason Cassidy

Be the first to comment