In early spring, health officials and providers across California braced for a flood of coronavirus patients. Spread of the disease elsewhere—such as New York, with hospitals and morgues overwhelmed—led epidemiologists to forecast a surge in the Golden State by mid-April.

That surge did not materialize in Butte County. Orders issued by Gov. Gavin Newsom requiring residents to stay at home as well as restricting public gatherings and non-essential businesses—combined with initial adherence to public health department guidelines on social distancing, hand washing and face coverings—seemed to work for many parts of California, especially in this semi-isolated rural county.

In fact, among health service areas tracked nationally, the Chico area had the lowest incidence of coronavirus heading into May. In response, that month, Butte County was one of the first two counties that the governor authorized to reopen earlier than mandated for the rest of the state. A federal medical station set up at Enloe Rehabilitation Center was packed up and shipped out.

Since then, coronavirus numbers in Butte County, as in many counties across the state, have risen sharply, especially over the past two weeks. As of July 13, the county’s Public Health Department had recorded 376 positive tests for COVID-19, with 233 coming just since June 26. Four have died, and of the 109 in isolation, six are hospitalized.

Even with the current uptick and without the federal field hospital in place, local health administrators have expressed confidence in the county system’s capability to treat coronavirus. They say that measures taken have, so far, kept the disease from reaching epidemic proportions locally.

“I would love to say that we did so well that we prevented the surge, but that’s yet to be seen,” Butte County Public Health Director Danette York said last week by phone. “It very well could be that the surge hasn’t happened yet.”

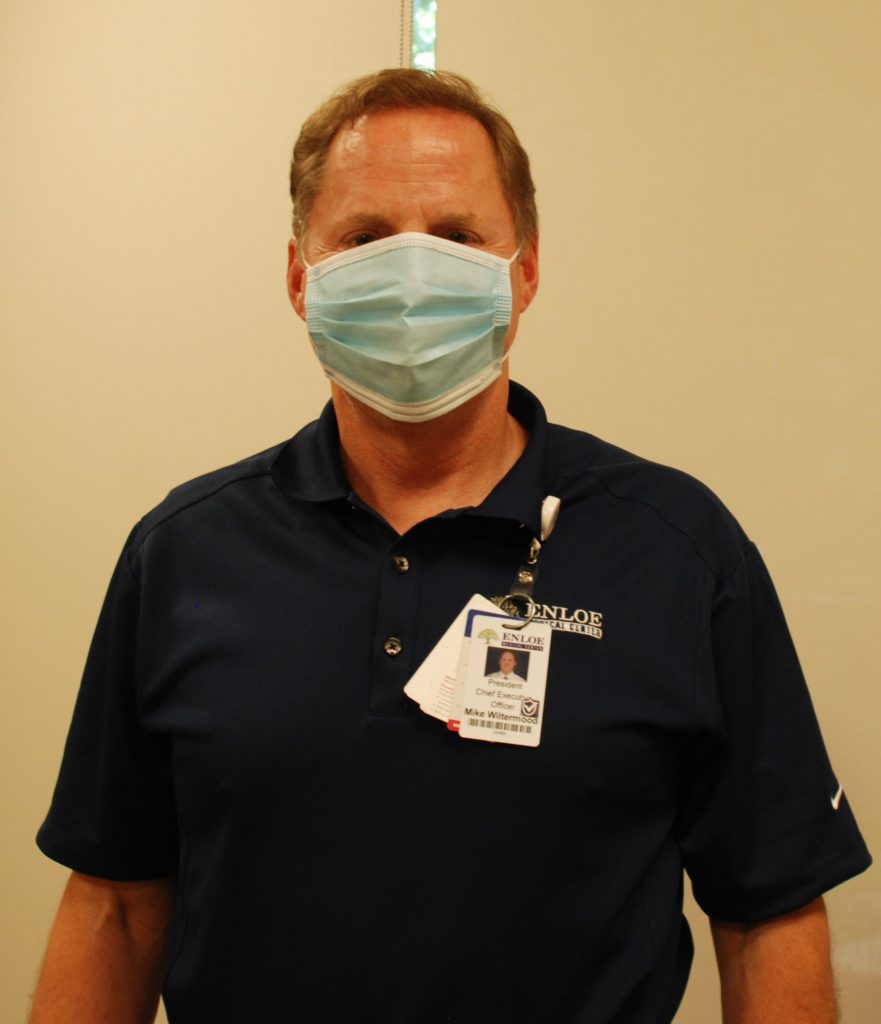

In light of the summer spike, Enloe Medical Center CEO Mike Wiltermood said, “maybe we just delayed the inevitable to some degree…. At this point we feel pretty good about our ability to continue to provide all services and keep our patients as safe as humanly possible with the equipment and supplies that we have.”

Prevention, preparation and unintended consequences

When the governor issued his initial orders, Butte County had the lowest incidence of COVID-19 cases in the nation. Nonetheless, the county’s three hospitals—Enloe, Oroville Hospital and Orchard Hospital in Gridley—joined others in preparing for surge conditions.

Hospitals stopped performing elective procedures (i.e., surgeries not critical for life-saving) and dedicated areas to isolate patients. The state government dispatched federal medical stations regionally to accommodate any overflow. The federal medical station in Chico opened in April and increased the county’s capacity for coronavirus by 125 beds, an additional 25 percent.

With space set aside to isolate infected patients, plus fewer procedures taking place, the hospitals had plenty of empty rooms to absorb a surge. Enloe was around half-full during this period, Wiltermood said. (Oroville Hospital and Orchard Hospital did not respond to interview requests.)

As preparations took hold, a new concern arose for Enloe personnel: decreased traffic in the emergency room. Judy Cline, director of the emergency department and trauma services, said her doctors and fellow nurses consistently saw far fewer people for the illnesses and accidents that normally require E.R. visits.

“It was frightening, because people seek care,” Cline said. “Where were they? Where were they going? What was happening to them? It was very distressing for us.”

At the time, doctors still admitted very ill non-coronavirus patients to the hospital, with ample rooms available, but the volume of walk-ins visiting Enloe’s E.R. dropped from an average of 235 to 135 a day.

Only in June did the E.R. start returning to what Cline called its “post-Camp Fire normal,” with traffic increasing to 200-plus a day.

“It actually makes our staff feel reassured: ‘Oh, our people are back,’” she said. “We don’t want people to have to come to the ER, but we knew they were coming before….

“We were just so worried, perhaps, that they were frightened to come to the E.R.,” Cline added. “Perhaps they were afraid of being a burden to the hospital, not knowing what we were dealing with.”

Along with E.R. activity returning, Enloe has resumed elective procedures. The hospital incurred a loss of $30 million from March through July, Wiltermood estimated; he expects the federal government will reimburse half that amount to the nonprofit organization, including costs for the FMS.

Should Enloe need to ramp up for a full-on surge, Wiltermood said the medical center could postpone procedures, reallocate space—the hospital’s intensive care units and south wing (for around 75 additional beds with ventilators), plus certain clinics—and, within 48 hours, convert the rehab center into a field hospital again.

“The most important concern is [if] people delay care that they really need because they’re concerned about either getting a COVID infection in a hospital or a clinic, or because they’re trying to be good citizens and stay away,” Wiltermood said. “I can tell you for an absolute fact that we have lost far more people due to delays in care than we have due to COVID.”

Take two

Butte County’s rise in coronavirus numbers traces to a convergence. As summer began, testing became more available locally, notably at the Silver Dollar Fairgrounds. The county advanced further into its reopening plan, with more retailers and restaurants welcoming customers. And quarantine fatigue set in—as York put it, “people began relaxing more” with prevention measures, thinking the disease’s contagiousness “was not such a high risk as it was or we initially thought it was.”

“All of those things combined could be setting us up for a perfect storm,” York said, “in that if we’re not careful, we are going to overwhelm our health care system.”

With California’s numbers still growing, Newsom yesterday (July 13) pulled back the reins on reopening by reimposing restrictions on indoor dining, bars, wineries, museums and family entertainment venues such as movie theaters.

“The initial plan for all the mitigation efforts was to flatten the curve, to prevent everyone from getting sick and overwhelming our health care system at one time,” York added. “It’s extremely necessary that everyone continues to be vigilant and participate in all of the activities we have been doing instead of getting relaxed and thinking that it’s over, because it’s definitely not over.”

Cline pointed out how “there’s so much we don’t know about this virus,” which is called a “novel” coronavirus because COVID-19 is new. Scientists are researching amid ever-shifting conditions.

“The complexity of this—just when you think you’ve figured this out, the weather changes and it changes all of your plans,” Cline said. “We cannot get complacent about anything that we have in place right now because we’re learning all the time.”

Wiltermood offered praise for medical care providers grappling with this unprecedented situation. On top of the uncertainties, medical facilities have struggled to procure enough personal protective equipment (PPE) to meet all safeguards and protocols. Supply lines have improved, he noted, with local manufacturers bridging the PPE gap with masks and face shields. Still, at his hospital, they’re taking nothing for granted.

“A significant impact of COVID is fear of the unknown,” he said. “When you see the social media posts of emergency room personnel [in other cities] quitting, or sick, or frustrated because they didn’t get the protective gear they should have—and you know that train is coming your way—for people to hang in there in spite of that potential danger was incredible.

“It certainly brought up issues of what we needed to address to protect our employees as well as our patients,” he added, “but everybody [has] showed up for work.”

Great article – amazing journalism!

Thank you for the report .Stay safe .