Domestic well users will be hit the hardest as Northern California continues to suffer from severe-to-extreme drought conditions in 2022.

That is one of the key takeaways from a Drought Impact and Analysis Study being prepared for Butte County by Luhdorff & Scalmanini Consulting Engineers. At the Tuesday (April 26) Board of Supervisors meeting Cab Esposito, a project hydrogeologist with the group, shared predictions that two to three times more wells in Butte County will run dry this year compared to 2021 based on groundwater level trends.

The intent of the analysis is to understand the impacts of the drought last year, with the ultimate goal of figuring out next steps for the county, such as updating policies or establishing an early warning system (e.g., a public dashboard to help residents identify if their wells are likely to go dry). The report analyzes several areas of economic impacts of the drought, including agriculture, public water supply, domestic wells, government operations and ecosystem services.

At the meeting, the supervisors mainly asked questions and requested more information. The analysis will be revised then presented to the county’s Drought Task Force, which will make recommendations to the board. The county also will host a public webinar in May, and then the final report will be released.

Esposito began his presentation with the bleak reminder that California experienced its third driest year in 2021, preceded by its 10th driest in 2020. California—which declared a statewide drought emergency in 2021—recorded its driest January and February this year in more than 100 years of records in the Sierra Nevada. Butte County has been in a local drought emergency since last summer. Last month, the state dedicated additional funding ($22.5 million) to respond to the crisis, with more than a third of that going to increased education on water conservation measures and practices.

According to self-reported data from the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) at mydrywell.water.ca.gov, 43 wells went dry in Butte County in 2021 (the county’s records only included 19). Butte County began collecting this data less than a year ago, in August.

Supervisor Tod Kimmelshue said he’d be shocked if that number is accurate, and anticipates that it’s much higher.

“I just can’t believe there were only [about] 50 dry wells in Butte County at this point in time,” he said.

The data is self-reported, so information such as the ages of the wells and how deep they are isn’t always included because the resident either doesn’t know or chose not to provide that info, Esposito said.

The drought impact analysis predicts that 77 more wells will go dry this year just on the valley floor, and the older the well, the more likely it will be impacted, Esposito said.

“They just weren’t drilling as deep back then, and they have an increased risk of going dry as water levels continue to decline during this drought.”

Esposito added that there was no groundwater level systems data they could draw upon to make predictions for the foothills, too.

While less than 5 percent of residents rely upon domestic wells across California, that percentage jumps to 25 percent in Butte County. And domestic wells are getting deeper and deeper in response to the drought, particularly in the Vina subbasin and foothill areas.

Responding to a dry well is not a cheap or quick fix. All of the Butte users who reported a dry well to the state last year said their issue was not resolved—a majority (38 percent) trucked in water, and just under a quarter (20 percent) said they could not afford it.

The cost adds up quickly: water deliveries cost $240 to $350 for 2,000 to 2,600 gallons of water; onsite storage containers cost $1,750 for a 2,500 gallon tank. (To put that into context, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) reports that on average, each person uses about 80-100 gallons of water per day for indoor home uses.) Drilling a new well costs $70 per foot (about $23,000) and the wait list is long, about one and a half to two years. For those who live in a water service area and want to hook up to the water main, that’s also an expensive endeavor that can cost anywhere from $3,000 to $10,000.

Fire season and firefighting needs also impact water availability for deliveries, said Kami Loeser, director for the county’s Department of Water and Resource Conservation. The drought analysis will hopefully inform the processes that need to be in place to grapple with both issues, she added.

When it comes to agricultural wells, Esposito said they were not a focus because there are less concerns about those going dry. Supervisors Tami Ritter and Debra Lucero replied that they wanted that agricultural well information (including depth and proximity to other wells) added to the report.

“If we’re excluding that agricultural data, we aren’t getting all the information that could contribute to the vulnerabilities,” Ritter said.

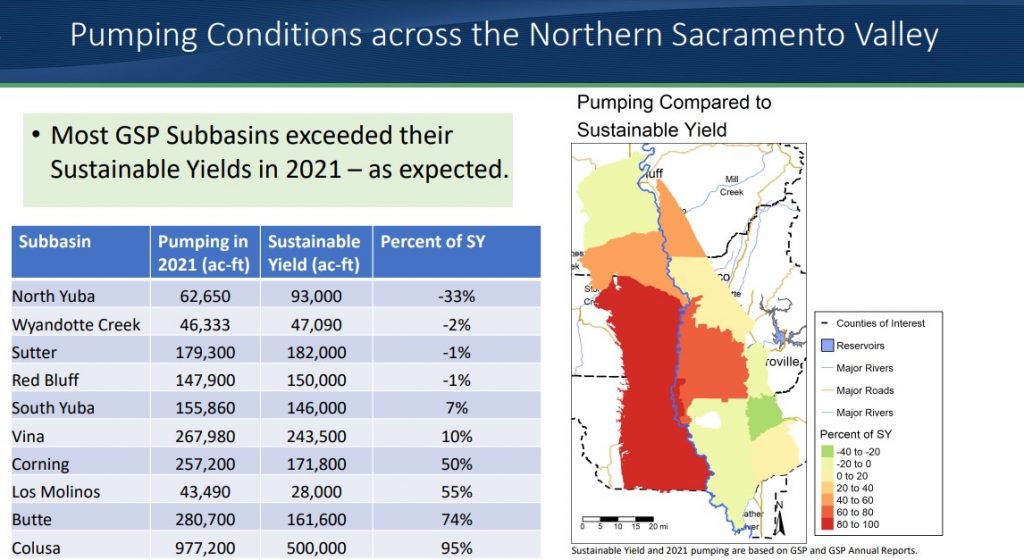

Other takeaways from the report centered on subbasin activity and groundwater pumping. For example, most Northern Sacramento Valley subbasins exceeded their sustainable yields—the maximum amount of water that can be withdrawn annually “without causing an undesirable result” (according to SGMA, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act)—in 2021.Though this is expected during a drought, Esposito added.

The Colusa and Butte subbasins pumped the most acre feet—977,200 acre feet for Colusa, which exceeded its sustainable yield by 95 percent, and 280,700 acre feet for Butte, exceeding its sustainable yield by 74 percent. Vina, the other major subbasin in Butte County, pumped 267,980 acre feet, and only exceeded its sustainable yield by 10 percent.

Lucero expressed astonishment at the numbers for Colusa, in particular, and said the report should explain the impacts of nearby subbasin pumping. Esposito replied that the USGS and California DWR are working to characterize large swaths of underground water systems to answer such questions.

The report also highlighted that Butte County did not have any crop idling (where farmers leave the land fallow and transfer surface water), or groundwater substitution transfers (where farmers transfer surface water and pump groundwater to meet crop requirements). County residents cannot sell surface water and pump groundwater without a permit, and none of those permits have ever been applied for, according to county staff.

“I’m proud of Butte County because we have [been] forward thinking in that regard,” Kimmelshue said.

And when it comes to the cost of doing business, even in a drought year, water represents only 5 to 10 percent of the total cost to farm in Butte County (compared to 15 to 30 percent in other parts of the state).

Lucero added at the meeting’s end that she wanted an executive summary to better explain the findings of the analysis to the public.

“I think the greatest context would be our groundwater sustainability plan,” she said. “How does what’s going on meet our measurable objectives and our thresholds? Where are we in that process?”

Loeser replied that the Drought Impact and Analysis Study will help the county make those connections between drought preparation and resiliency alongside other long-range plans, including the general plan and subbasin groundwater sustainability plans.

Be the first to comment