This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

In September of 2020, California was in the midst of a record-setting heat wave. The hot and dry conditions fueled fires all over the state, and smoke from wildfires hundreds of miles away hung over the Bay Area for weeks. Andrew Kornblatt woke up one morning at his home in Berkeley to find that the air had grown cool and still, and the sky was an eerie orange.

“It hit at the lizard brain part of your noggin, trying to tell you to just run,” Kornblatt said. “And you’re thinking to yourself, well where are you going to go with this flight response?”

By November, Kornblatt and his wife, who both grew up in the Bay Area, had left California for Oregon.

They’re hardly alone. At least 57 percent of Americans believe that weather- or climate-related events will influence their future moving decisions, according to a recent study published in Climatic Change.

“We’ve never asked this kind of question before in the context of the United States. Because climate-induced migration has always been discussed in the context of the global south,” said Byungdoo Kim, a doctoral candidate in environmental communication at Cornell University and lead author of the study. “But recently, we’ve been through a lot here in the United States.”

It’s not just California. The entire Southwest is getting hotter and more arid. The Northwest is seeing wetter winters, but drier, more fire-prone summers. Sea level rise is leading to more flooding along the East Coast. And the Midwest is facing more intense heat waves, heavy rainstorms and the spread of disease-carrying insects like mosquitoes and ticks.

Kim cautioned that the recent study is based on survey data from 2016. Since then, historic levels of flooding have inundated the Midwest. Texas has been battered by floods from Hurricane Harvey and deadly freezing from an epic winter storm. And California has endured five of the biggest fires in its recorded history — to name just a few of the billion-dollar climate disasters to hit the United States in the last few years.

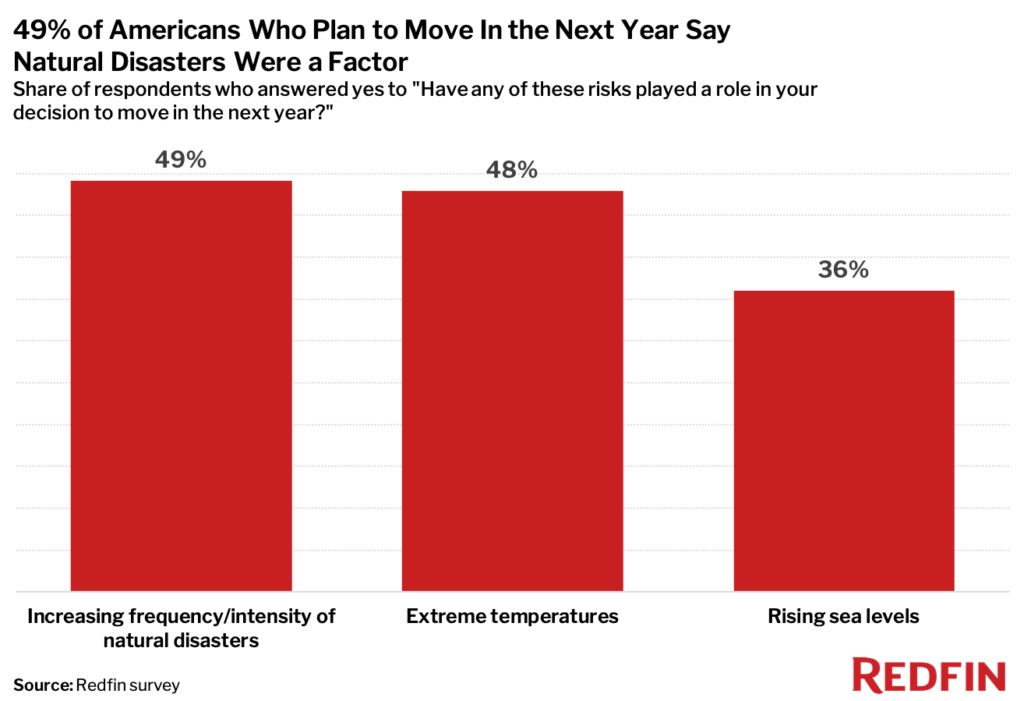

In a more recent survey, conducted in early 2021, around half of people who plan to move in the next year said that the increasing frequency and intensity of natural disasters was a factor in their decision.

Many Californians are already migrating elsewhere. Last year, for the second straight year, more people left the Golden State than moved to it. California’s population continued to grow because of new births, but it grew more slowly than at any point since 1900. And while an analysis from the California Policy Lab found “no evidence of a pronounced exodus from the state,” reports abound of Californians relocating to Idaho, Texas, Oregon and Washington in droves – much to the dismay of their new neighbors.

When Steve Smith moved from Oakland to Bellingham, Wash., last year, he made sure his neighbors knew he was a Coloradan by birth, even though he had spent the last three decades in California. For Smith, an artist and writer, the 2020 fire season was a breaking point. His marriage was dissolving. The culture of the Bay Area was shifting with the growth of the tech industry, and the rising costs of property taxes and insurance threatened to make the house that he and his wife owned unaffordable. After smoke kept him stuck inside for several weeks last year, he was done.

“I loved living in Oakland. California was the promised land,” Smith said. “But it just kept getting harder to live there.”

When he called U-Haul to rent a truck a few weeks before the move, a representative told him there was only a small chance they would have a vehicle for him.

“I asked why, and she said, ‘Because no one is moving here,’” he said. Indeed, California saw the greatest net-loss of U-Haul moving trucks of any state in 2020.

Even within California, many residents are moving away from high-risk fire zones. Virginia Partain, a former high school teacher in the town of Paradise, is one of them. When the Camp Fire engulfed her house in the fall of 2018, Partain got stuck in a line of traffic on one of the four roads leading out of town.

“We were stuck for hours, not knowing if we were going to burn to death,” she said. After that, she knew that she didn’t want to rebuild in Paradise.

“I’m not going back up the mountain,” she said. “I know it’s going to happen again. I don’t want to be in my 80s and trying to get out.”

Most of the 86 people who died in the Camp Fire, the deadliest in state history, were elderly or disabled. Few of the survivors opted to stay. The population of Paradise dropped from close to 27,000 people in 2010 to a little more than 2,000 a year after the fire.

After losing their house in the Camp Fire, Donna Patterson and her husband bought a home in northern Idaho. It was less expensive to move than to rebuild in Paradise, and they wanted to leave behind the charred landscape, which served as a painful reminder of their traumatic escape.

“It’s not the town we loved,” she said. Patterson also wanted to protect her health. She has asthma, and it felt like every year she was suffering through more days with smoke-filled air, she said.

Research shows that California’s fire season has been growing longer, and after another dry winter, the state is queued up for a potentially devastating summer and fall. UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain wrote on Twitter that, in April, vegetation flammability in Northern California reached levels normally not seen until July, the height of the dry season.

It’s not just California. Across the country, wildfires are growing larger and erupting in areas that were previously well-insulated from blazes. For this reason, Partain believes that it’s a “myth that you can somehow outrun climate change.” After retiring from teaching in 2019, she briefly considered moving to Talent, Ore., where a friend who had also lost her home in the Camp Fire had settled. Then, in the fall of 2020, a wildfire swept through Talent. Partain decided instead to stay in Chico, the city where she grew up, some 15 miles down the mountain from Paradise.

The growing threat of climate change is what ultimately convinced Justin, who asked to be identified by his first name only, to stay. His family was renting in Marin County, but looking to buy. Trapped inside by smoke during the 2020 fire season, he and his wife endlessly discussed climate change. Where would it be safer to raise their two-year-old daughter? Everywhere they looked came with its own risks or tradeoffs.

“You can’t escape climate change,” he said. “Maybe this is the future. Maybe there’s always going to be big wildfires and smoke issues in ways that we haven’t experienced before, but we love this area, and if dealing with fires is what it’s going to take to live here, then we’re going to deal with fires. I’d almost rather just go down with the ship than have to learn a whole new area and be a climate refugee.”

Justin and his wife are buying a house in Marin County from a couple who decided to leave California and its wildfires to move to Texas.

Kate Wheeling writes for Nexus Media News, a nonprofit climate change news service. You can follow her @KateWheeling.

thank you, nice post.

Thanks for posting