Like many parents, Dan La Bar felt the impact of the coronavirus emergency profoundly in March when stay-at-home orders from Gov. Gavin Newsom changed how schools teach and students learn.

La Bar works as an administrator for three homeschooling charter schools, including his three children’s, South Sutter, for which wife Trelawney teaches. With the whole family sequestered, the La Bars had to fill the void for educational enrichment normally conducted elsewhere.

For instance, oldest son Jonah, 12, had attended a hands-on science class outdoors. “Could you imagine bringing Bidwell Park to a computer?” La Bar asked. That’s what Jonah’s school had to do to recreate his Earthbound Skills course online.

“That was a struggle,” he said. “The other thing that I saw personally with my children is they withdrew from certain activities.”

La Bar, previously principal at Inspire School of Arts & Sciences and a former Chico High teacher, started using the term “crisis schooling” because “even homeschoolers weren’t homeschooling,” strictly speaking. The change, he said, “was a jarring shift…. We all understand it was for the right reasons, for safety and prevention methods—and teachers were doing their best—but educationally it was not the best situation.”

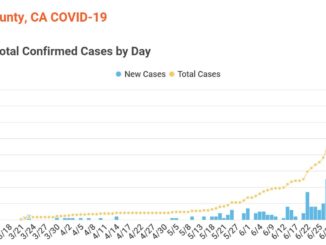

Since the governor has not lifted all restrictions on public gatherings, local officials face unusual, uncertain circumstances as they head into fall. Administrators have to factor numerous variables and contingencies into their planning, leaving them unsure what exactly the next school year will look like.

“Oh, my gosh, if I had a crystal ball and could answer that question, I’d be the biggest hero around,” said Kelly Staley, superintendent of the Chico Unified School District.

She and other education leaders have the benefit of previous crisis experience, including the Oroville spillway evacuation and the Camp Fire. They also know what families want, based on surveys. CUSD’s results matched what the Butte County Office of Education learned from other district and charter school surveys.

“By and large, parents really want their children to be back in school—the vast majority,” BCOE Superintendent Mary Sakuma said. “What I anticipate seeing is school districts will offer more choices than perhaps they have been able to in the past….”

CUSD, which serves 12,400 students, found 70 percent of parents favor a return to traditional instruction, with just 10 percent preferring their children remain home. The other 20 percent would like a blend of in-person and online school. Staley said the district is planning for these three options, though doesn’t expect final approval from the school board until July 15, after at least another round of surveys and further input from BCOE and health officials.

“I can tell you the process part of it,” Staley added, “but I cannot tell you what [school] will look like because nobody knows that.”

The superintendents do know that local circumstances will shape the decisions. They’re considering guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the California Department of Public Health, relying most heavily on Butte County Public Health, but each district will determine how to enact health and education policies.

For school districts in the county, Sakuma said, BCOE will issue recommendations rather than rules. Districts will set standards for operating and re-closing, though the county’s public health officer also may close schools.

“What we’re really going to focus in on … are the things that will provide confidence to families, and to our teachers and staff, to confidently return,” she continued, “what measures we feel like we need to have in place.”

Staley, who like Sakuma and La Bar spoke with the CN&R by phone June 15, said she doesn’t “foresee every teacher being forced to wear gloves and a protective gown. We are not planning for plastic partitions down classrooms.”

State orders limit the size of gatherings, and the social distancing buffer of 6 feet places constraints on class sizes. Jay Marchant, CUSD’s assistant superintendent of educational services, said the district is drafting several scenarios depending on the coronavirus situation: business as usual, fewer students on campus or a resumption of distance learning. To reduce student density, CUSD may rotate primary-school students, who would come to class two or three days a week; and go to three-by-three blocks in secondary schools, with three longer classes covering a year’s worth of material in a semester.

Cutting class sizes further—something CUSD discussed—would require additional facilities and staff.

“There are some ideas that sound outstanding but just are not doable,” Staley said, “especially if we’re looking at tightening of the purse strings with the state budget.”

Be the first to comment