By Scott Thomas Anderson

It’s hard to believe that it happened in Oroville of all places – that an embodiment of the land’s lost voices, and a final survivor of California’s darkest crimes, appeared in the flesh near barking dogs at a slaughterhouse on the edge of town.

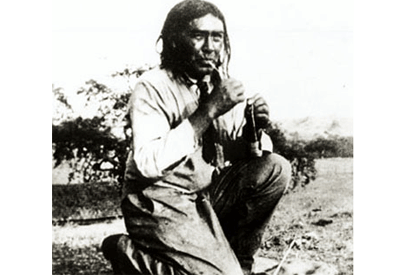

He was sun-scorched and starving. He spoke a language that no one, including other Native Americans in Butte, could really understand. There was a deep-reaching memory reflection that saddened his eyes.

This stranger came to be known as Ishi. He was the final member of the Deer Creek Yahi Tribe, which stayed cloaked and hidden by the old ways into a new century. Newspaper men of the era had a flashier description: They trumpeted Ishi as “the last wild Indian in the West.”

The rugged romanticism embedded in such headlines was, of course, the opposite of reality. It appears the main reason Ishi was concealed from white settlements in the Lassen foothills was because, as a child, he’d witnessed his tribe repeatedly attacked by a brazen, state-sanctioned frontier murder gang. Ishi wasn’t willfully enjoying the freedom his people had known in Butte and Lassen since time immemorial so much as hiding from a Euro-American society that had allowed the wholesale slaughter of his family and friends.

It was only after the few remaining members the Yahi were dead that Ishi revealed himself. By then, there was no human left who could speak his language. Ishi was the only one knew the stories animating the soul of his people. It’s believed that he was around 50-years old when he stepped out of oak woodlands near Oroville in summer of 1911.

Here is what the National Park Service says about the spot where Ishi first appeared:

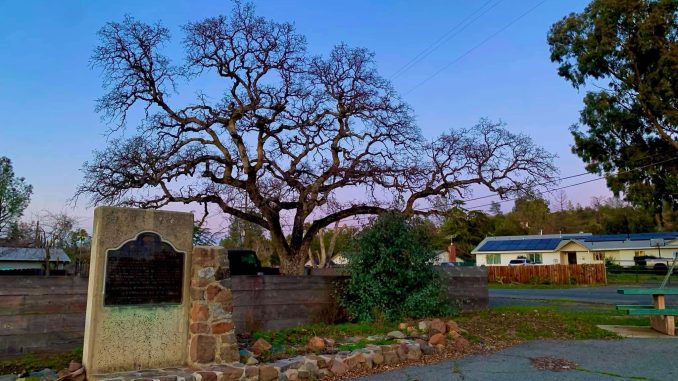

Ishi’s Hiding Place is located at the corner of Oak Avenue and Quincy Road, at the site of the old Ward Slaughterhouse about two miles east of Oroville. The foundation of the slaughterhouse is extensively deteriorated because of weathering. Several residences sit on the upper part of the one-acre site, while the slaughterhouse remains are on the lower portion of the property. An oak tree stands where Ishi was first seen.

Last week, I went to that spot at sundown. It would be hard to describe it as “two miles east of Oroville” in our current moment. It’s surrounded by houses along a semi-busy street that’s woven into the modern city. The place is a tree-dotted intersection with a relaxed country feel, but it’s very much a neighborhood. Its foundation of rock and mortar that Ishi saw at Ward’s Slaughterhouse is now barely perceptible from the road. Even the large stone memorial that was put up in 1966 equals a witness-mark that can be missed while making the turn. As I watched stars strengthening over the twisted oak that Ishi once passed by, and a coral sky-fire falling on the blue coldness over the westward buttes, I was struck by how encompassing the erasure of time can be. A man who’d been the last breathing repository of an entire human experience on the earth made a decision here; and were it not for a state parks commission some 55 years later, the exact spot would have been entirely lost to living memory.

Without historians, journalists, local raconteurs and Native storytellers, Time itself will make such places forever invisible.

In this case, that didn’t happen.

So, what became of Ishi after appearing in Oroville? He was ultimately taken to San Francisco and put into the care of anthropologist Alfred Kroeber (whose daughter would later become one of America’s most celebrated authors of feminist and environmentally informed fantasy literature, Ursula K. La Guin).

Kroeber made over 400 wax cylinder recordings of Ishi sharing his people’s stories in their Yahi dialect.

The doctor also started combing through records and archives to find out what had happened to Ishi’s tribe. What he discovered was a tale of horror. Beginning in 1865, a settler “militia” began riding through Yahi camps in the hills between Tehama and Butte, their guns mercilessly blazing. The contours of their killing sprees were recorded by dairies and newspapers of the day. A breakdown of events, at least as we know them, is as follows: “the Workman Massacre” – 40 Yahi killed; “the Silva Massacre” – 30 Yahi killed; “the Camp Seco Massacre” – 45 Yahi killed.

In the case of the “Three Knolls Massacre” that happened between Oroville and Chico, Ishi’s father was one of the 40 Yahi who were cut down.

Students of grim Western literature may know that Cormac McCarthy’s “Blood Meridian” was loosely based on the crimes of a man named John Joel Glanton, who led a mercenary gang of “Indian-hunters” that got paid by the scalp from various governments in the Southwest. Glanton’s massacres were aimed at the Apaches, the Yuma and small farming tribes that lived in the Sonora Desert. Today, even this grisly narrative is barely known; but far fewer people understand that there were men like Glanton and his crew operating in Northern California before and after the Civil War.

“We should also remember that those bands of Indian hunters could receive local compensation for their actions,” historian James Rawls told PBS’s American Experience. “Many communities through Gold Rush California offered bounties for Indian heads, Indian scalps, or Indian ears. And so, the Indian raiders could bring the evidence of their kill in, and receive direct local compensation. Furthermore, the state of California passed legislation authorizing more than a million dollars for the reimbursement of additional expenses that the Indian hunters may have incurred.”

This is California’s numbing original sin. And the state has only begun to grapple with it in the most basic ways over the last few years. News & Review has reported on efforts to bring attention to the modern trend of missing and murdered indigenous women across the West (including in Northern California); and, on a very actionable level, a new law that forces universities to return Native American artifacts and human remains to their tribes. CN&R contributing writer Samin Vafaee recently noted how the same forensic anthropologists helping homicide detectives solve cold cases are also using their skills to identify where academically-seized Native remains came from, and thus get them back to their rightful ancestorial groups.

The foothills’ shameful history of grave robbing

The issue of stolen native remains hits close to home for me. When I was a kid, I lived within walking distance of a well-known and well-documented Miwok burial ground. This was in Amador County, up in its high country of Pioneer – a place where the rolling oak woodlands begin to sweep into the mountainous terrain of the Sierra.

The field I remember had what’s known as a large “grinding rock,” meaning a huge, flat slab of granite in the grass that’s pocked with an array of chiseled depressions. State historians define these objects as granite with “mortar cups that formed in a stone slab as the Miwok people pounded acorns and other seed into meal.” In the Miwok language, the holes are referred to as “Chaw’se.” So, there was no doubt in my neighborhood that this was a cultural site: Not only did it have an impressive grinding rock, it was only three miles, as the crow flies, from Chaw’se Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park, which authorities formed to protect Miwok heritage in 1983.

Since the time I was 6 or 7, in the early 1980s, I heard adults talking about a cache of human remains that had been accidentally unearthed in that field while PG&E was digging a trench to bury wires. All these years later, there’s no documentation online of such an incident taking place; but that is perhaps not surprising, given the handshake nature of how Amador County elected officials dealt with business owners and corporate officials in the 1970s and early 80s. Decades later, when I was a cub reporter in the area, some elder tribespeople vaguely acknowledged to me that the story was true, though they declined to offer details.

While I don’t know exactly what happened with the so-called trench incident, I do know – from my own eyes – that local people would sometimes dig in that field, as if they were amateur archeologists, looking for Miwok beads, stone arrowheads and even human bones. When I do the math in my head, this would have been at roughly the same time that other locals were scrambling to convert Chaw’se into a state park and officially protect that spot’s bodies and artifacts from similar random plunder. As ghoulish as all this sounds today, it probably wasn’t illegal at that time. The federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act didn’t become law until 1990, which was five or six years after some of my clearest memories of this sporadic digging. California didn’t pass its own version of that law until 2001.

From the best I can recall, having been a little nosy kid who constantly eavesdropped on adults, not only were there no legal repercussions back then, there was not much in the way of social blowback (outside of reactions from the tribal community, of course). I never witnessed anything resembling reproach or shaming from one local to another over these digs, only the occasional superstitious warning that it was “bad luck” to put a spade in that sacred soil.

There was also a yarn that circulated throughout Pioneer that a man had supposedly taken a Miwok skull out of the ground and brought it home, only for his life to be “ruined” by one catastrophic turn of events after another. Prior to the NAGPRA becoming law, which the Sheriff’s Office did start enforcing, the only thing holding people in check around the field were fears of the quasi-mystical.

One time, when I was in high school, a friend of mine was walking by the grinding rock after a hard rainstorm and found a handful of beads that had washed up into the grass. He collected them and later brought them to a Native American art supplier to see if he could get some money. He was warned by the art supplier, with quite a bit of gravity, that he was holding onto burial beads, and that he should immediately put them back where he found them – before he came to regret it.

My friend followed those admonishments.

By the time I was a budding reporter in Amador and Calaveras counties, in the late 2000s, the area’s three federally recognized bands of Miwok Indians had the financial means and political clout to put a stop to the desecrations of their burial sites for good. Even though locals had mostly abandoned the pastime after it became federally illegal, a black market had suddenly sprung up with the internet for Native American artifacts. Basically, unscrupulous individuals could get serious cash for digging them up and shipping them to private collectors, many of whom, weirdly, were in Germany.

Working on a news story about the topic, I spoke with a younger member of the lone Band of Miwoks, who related how he felt about this whole horrible history of grave looting that had gone down in Amador.

“How would you feel if you were driving by the Jackson Cemetery,” he asked me, “and you saw me and my friends breaking into all the crypts with pickaxes and shovels, and all we did was smile and wave at you, calling out, ‘Hey, we’re on a treasure hunt!’”

I took his point.

In 2018, The New York Times ran a story with the headline ‘Berlin Museum Returns Artifacts to Indigenous People of Alaska.’

“The foundation overseeing state museums in Berlin returned nine artifacts to indigenous communities in Alaska this week after it determined that they had been taken from a burial site in the 1880s,” the report began. “The objects were taken from graves without permission of the native people, and thus unlawfully.”

Hermann Parzinger, the president of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, added, “They don’t belong in our museums.’”

So, as of five years ago, the Germans have been getting serious about correcting a history of grave-robbing in Native American cultural sites. But do you know who hadn’t gotten too serious about it? California’s colleges and universities, which collectively had a vast deposit of indigenous remains that have been stored up over the last century. That’s the whole reason the new law was just passed.

California continues to wrestle with its shadows. It’s still asking itself what can be done to re-dress the ultimate sins once committed here. In the case of Ishi, one simple thing would be updating the memorial plaque at the intersection of Oak Avenue and Quincy Road in Oroville. This engraving, made in 1966, does allude to the genocide that happened in Butte County in fairly plain English, stating, “The white man brought death to the Yahi by the gun, by disease and by hunger.” However, the last line of it feels off. The plaque ends by saying that Ishi’s death in 1916 “brought an end to Stone Age California.” That sentence has an ethnocentrism that one can feel in their bones. And it’s also not nearly poignant enough for capturing what the extermination of the Yahi – and Ishi’s incredible survival story – mean to our understanding of state history.

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the writer and producer of the true crime podcast series “Trace of the Devastation.”

Thank you, Scott, for this soul-rending reminder of the loss of life and history of California’s indigenous tribes at the hands of early European settlers. We can still learn so much as we consider how and why we remember.

As someone from Minnesota , I wouldn’t know about Ishi and the Yahi were it not for your account. Thank you for keeping them alive.

Scott, great article. Did Gen. Bidwell and Annie Bidwell participate, in any way,in the genocide?