By Ken Magri

“The ache for home lives in all of us, the safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.” – Maya Angelou

Since the abolition of slavery in 1865, civil rights groups have seen discrimination in land and home ownership as a cancer in the nation.

Experts say that for reasons involving race, religion, gender, national origin, low-income, politics and/or sexual orientation, discriminatory housing policies and financial strategies have conspired to keep citizens – most often people of color – from building generational wealth through home ownership.

To better understand this history, the News & Review compiled an informal timeline of discriminatory housing practices, sometimes with state and local aspects, beginning with a history of “restrictive covenants.”

Restrictive covenants and neighborhood associations

Beginning in the 19th century, restrictive covenants were legally-binding agreements throughout all-white American neighborhoods that prevented any home owner from selling to a minority family.

Convinced that racial exclusion would increase home values, “restrictive covenants” were written right into property deeds. They became more widespread throughout California after a 1919 State Supreme Court ruling declared that these restrictions were discriminatory, but still legal because they were written private agreements outside of government enforcement.

Local associations were formed in neighborhoods to enforce the exclusionary agreements. If a home owner sold their property to a non-white family, the neighborhood association could sue to nullify the sale and force an eviction.

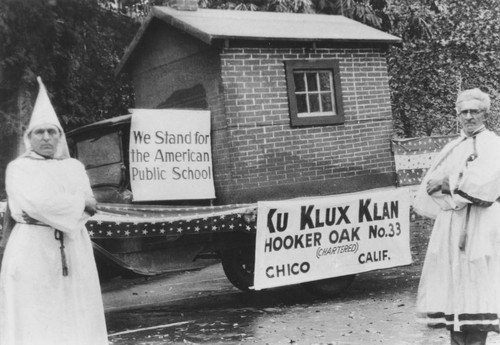

While not a direct result of that 1919 court ruling, in 1920, Chico allowed a Ku Klux Klan parade to march through downtown. The demonstration was organized by the local “Hooker Oak KKK Chapter #33,” which lobbied for white dominance in every aspect of local culture, including employment, education and housing.

Racial covenants were ruled unconstitutional in 1948 by the US Supreme Court. Although the remaining covenants have not been legally enforceable for decades, they still existed in written form. It took a 2022 state law, AB 1466, to require California’s county recorders to finally eliminate all former discriminatory language remaining in many of these property deeds.

Introduced by former Democratic Assemblymember, now Sacramento Mayor Kevin McCarty, AB 1466 officially forbids discriminatory language in housing against “race, color, religion, sex, gender, gender identity, gender expression, sexual orientation, marital status, national origin, ancestry, familial status, source of income, disability, veteran or military status, or genetic information.”

Redlining maps

Between 1934 and 1968, denying home loans based on where people lived was common, even if they qualified for a loan. Neighborhoods with lower incomes, or those with a higher amount of non-white residents, were lined out in the color red on city maps, giving the practice its name.

The maps were created by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), a government sponsored housing lender which rated neighborhoods from “Best” to “Hazardous.” The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which also used HOLC maps, was even more discriminatory in its lending policies.

For 34 years, the FHA redlined core urban neighborhoods and African American neighborhoods in particular.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed the practice. But even today, the Federal Reserve Board continues to monitor and enforce illegal redlining.

Chico was too small in the 1930s to have a HOLC map drawn up. But bankers and other creditors likely needed no map to tell them where the low-income neighborhoods were located.

Chico farmers recruit Blacks from Richmond

During World War II, Richmond, California, was a hub for war industry factories with such a need for workers that African Americans were eventually hired after the supply of white laborers was exhausted. They were paid well, but lived in segregated temporary housing until the war ended. By 1946, African American unemployment soared in Richmond, as documented in Richard Rothstein’s book “The Color of Law.”

Meanwhile Butte County experienced a record bumper crop of almonds in 1946 and desperately needed more farm labor. Prisoners of War who worked the harvests were gone and minority migrant laborers already moved on to other towns for their harvests. New laws protected children from performing certain farm labor jobs, and whites in the area wouldn’t take these farm jobs because they paid so little.

To solve the problem, the local Growers Farm Labor Association (GFLA) and the federal Emergency Farm Labor Project (EFLP) recruited 125 African-Americans laid off from Richmond factories to come up and harvest almonds.

At the time, the African American population of Chico was less than one percent.

Temporary barracks were set up at the fairgrounds and townspeople were told the African American recruits were well-educated, had the right skills and simply needed work.

“Ownership of property and stability of residence was emphasized,” according to a 1951 account called The Wilson Record, perhaps to convince locals that the new workers would return to Richmond after the harvest.

But racist rumors spread that these recruits didn’t know how to harvest almonds, that white women would not be safe after dark, and that Richmond would pass laws to prevent the African Americans from returning home.

Once they arrived, a white backlash began with merchants putting up “White Trade Only” signs in their store windows. One store owner said he felt sorry for his regular African American customers, but due to pressure from white customers, “I had to put up a sign.”

When Chico’s police chief, church leaders and newspaper pleaded for the merchants to take down their signs, a few complied. But their main reaction was to accuse town leaders of being secretly racist themselves.

“How many of them have colored members?” one Chico merchant was recorded as saying in the Wilson Record, referring to local churches. ”How many of them would open their homes to these Richmond darkies? Not a one, I tell you.”

The harvest went well that year, producing a record crop with no worker incidents. But locals were intent on keeping African Americans from establishing residency in Chico.

“We didn’t keep them out like we wanted to,” a property owner was documented as saying in the record, “but we are going to make sure they don’t get any foothold.”

Chico property owners opposed the removal of race-based restrictive covenants while churches worked to keep African-Americans out of their congregation. Even the farmers, who were desperate for these African American workers, attempted to pay them less than regular farm laborers for the same work.

As one long-time student of California farm labor stated at the time, “If you want to understand what is happening to Negro farm labor in this state, then study what happened to the Chinese in the 1870s, the Japanese in the 1890s and later to Mexicans and Filipinos.”

Chapmantown and the demolition of Daisy Lane

In 1957, CSU Chico sociology professor Richie Lowry and his students conducted a demographic study of Chapmantown, a low-income unincorporated neighborhood surrounded by Chico city limits.

Their report documented sub-standard living conditions, especially for a tiny number of Black home owners and renters. Chapmantown residents were among Chico’s poorest. Yet 91% were white and an additional 3% were singled out as “Caucasian non-whites of European origin,” a term describing Eastern Europeans, Greeks and/or Italians.

Chapmantown’s blighted history was blamed on “discrimination against minority groups and the lack of low-cost housing.” In publishing their study, Lowry and his students urged the need for government assistance.

Daisy Lane was a very short street in Chapmantown, partly populated by poor African American families. Located one block north of Humboldt Avenue between Linden and Willow Streets, Daisy Lane was declared blighted and bulldozed after a 1958 referendum approved a 100-unit affordable housing project in that location. The story was chronicled in a 2022 News & Review article.

“Because fewer than 12 of the residents of Daisy Lane were registered to vote, the city could push through annexation as an ‘uninhabited area,’ bypassing the opportunity for them to contest the arrangement,” said the article.

Exclusionary zoning, credit rationing and single-family homes

Exclusionary zoning describes local discriminatory policies that determined land use, lot sizes and which types of housing may be built in a neighborhood. The practice started in Baltimore in 1911 and became common everywhere after World War II.

These zoning ordinances prioritized single-family-only housing on larger detached lots as a form of passive segregation, making the homes unaffordable to lower-income buyers, mainly non-whites. The ordinances also curtailed the building of middle housing (duplexes, four-plexes, and other multi-family living structures) which were more affordable and took up less land.

Credit rationing was the biased restriction of access to credit based on an obscure “set of criteria” that allowed yet another reason to deny a home loan. Experts say that, in reality, the criteria depended on the buyer’s race, gender, religion or national origin.

“Discriminatory credit rationing helped prevent the American suburbs from being integrated, and it turned out to be “just as effective as redlining in maintaining racial and class divisions,” according to historian and UC Berkeley professor emeritus T. F. Tierney.

In 1964 a study of Chico’s Black population was conducted by CSUC Sociology Professor James Haehn and five of his students, with assistance from the local NAACP chapter. The study included information on population, education, occupations, annual income, housing conditions and general attitudes about the city.

The study found that most African Americans who lived in Chico were concentrated in the Mulberry neighborhood. Out of the 19 households that reported being unsuccessful when trying to find Chico housing in a better neighborhood, 17 said that racial prejudice was the main barrier.

The 1964 study also mentioned a condition of wider discrimination in other aspects of Chico life, like African Americans having to take jobs beneath their education and skill levels, and being paid less for those jobs. The resulting lower incomes made the opportunity for better housing unaffordable to them.

The study concluded that, due to this combination of discriminatory practices “the social and economic situation of local Negroes is a product of the education-occupation-income-housing cycle.”

This illustrates how zoning, low pay, credit denial and unaffordable homes thwarted the upward mobility of Chico’s African American population.

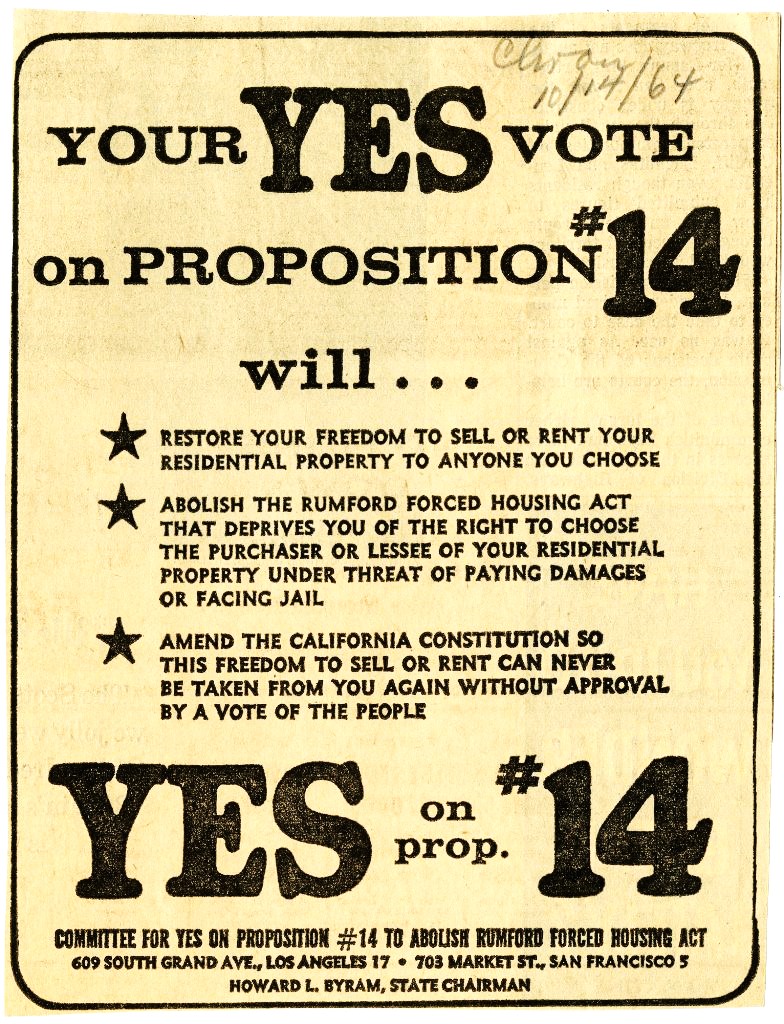

California voters and Proposition 14

In 1964, California’s voters overwhelmingly passed Proposition 14, a ballot initiative that gave homeowners the legal right “to decline to sell, lease or rent such property to such person or persons as he, in his absolute discretion, chooses.”

It was written to apply to Black, Asian, Latino, Jewish, female and other home buyers without specifically mentioning them.

When Proposition 14 passed, it nullified the 1959 Unruh Act which banned housing discrimination based on sexual preference. It also overturned the 1963 Rumford Fair Housing Act, named after California’s first African-American legislator William Rumford, which banned housing discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin.

Proposition 14 had been endorsed by the John Birch Society, the National State’s Rights Party, local chapters of the White Citizens Council, the American Nazi Party and the Californian Republican Party.

Butte County passed Proposition 14 with 69.3% of the vote, five percentage points higher than the state average, according to the California Secretary of State.

Governor Edmund G. Brown’s administration took the proposition to court, and in 1966 the California State Supreme Court ruled it violated the 14th Amendment to the US Bill of Rights. But it took an additional Supreme Court Ruling in 1967, “Reitman v. Mulkey,” to finally confirm California’s court ruling.

Use permits and students who rent ADUs

In 2008, the Chico City Council and the Chico Avenues Neighborhood Association formed a committee to create the Avenues Neighborhood Improvement Plan. It argued for special zoning and use permits to bypass a state law allowing second dwelling units (called ADUs) in residential backyards.

“Their number, location and design continue to be issues of concern for neighborhood residents,” noted the report.

The committee singled out “students” who were renting most of these units as the problem.

According to a 2019 survey on housing insecurity among CSU Chico attendees, “Students of color have 1.66 times the odds of being housing insecure relative to their white counterparts.”

The survey was conducted by professors Jennifer Wilking, Susan Roll and Mariah Kornbluh.

Corporate home-buying, the new exploitation

Across the nation, corporations, trusts and hedge funds known as “property investors” purchase tens of thousands of homes per year, turn them into rental units and wait for the values to go up. The practice grew after the 2008 economic crisis.

These are not the “We Buy Any Home” instant buyers who make extremely low offers to desperate sellers, then “flip” the houses for a quick profit.

Property investors are companies such as Progress Residential, the Blackstone Group and its subsidiaries that can buy in bulk and secure special interest rates as low at 2%. It allows them to make higher all-cash offers without actually paying a higher price. These corporate buyers help close the deal by waving inspections and appraisals, something individual bidders can’t do.

Corporate home buyers target entry-level homes in order to shut out first-time home buyers, hoping to turn them into new renters.

It is considered such a problem that Assemblymember Alex Lee (D-Milpitas) introduced AB2584 last year, a bill to curb corporate purchases at 1,000 houses. Companies such as Invitation Homes, a Blackstone trust, “own thousands of homes in California alone, targeting areas prone to higher rent growth,” said the assembly member when he introduced the bill.

Assemblymember Lee added “if someone’s dream is to be a homeowner, then they should have a fair opportunity to achieve that goal.”

That bill is currently stalled in the state house.

The lasting effect

There is an accumulative negative effect to all of these discriminatory strategies practiced over the decades. Across the nation, Black, Latino, Asian and Native American families continue to have proportionately lower homeownership rates than whites, according to the Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies.

While not forgetting about what happened to Northern California’s Native Americans who were slaughtered in the 19th century, or about the Japanese families who lost their properties and were interned during World War II, a local understanding of past discriminatory housing practices should instill Chico’s citizenry and leadership with more wisdom and compassion when planning for the future.

“The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it and till it by our own labor.” –African American Minister Garrison Frazier to General William Tecumseh Sherman in 1865.

Well, this was a disgusting journey down memory lane, but only marginally relevant except in historic context for the whole USA. However the corporate ownership of housing is an extraordinarily serious problem and needs to be stopped. They are buying up apartments, housing, and mobile home parks. Like some of our predatory downtown landlords, they make money by leaving properties open and jacking up rates. This is something that MUST be stopped. Frankly, 1000 properties is WAY too high a limit. Chico needs to begin a NON occupancy tax which punishes those who sit on properties and take write-offs for losses. I drive around and wonder why we reward non-productivity by the moneyed class. Incentivize productivity and occupancy for owners and landlords…and punish those who sit on empty property.

Agreed!

I find the opening photo horrendous! Chemical front yards, not much backyard. “ticky tack” homes.

Great article. This type of discrimination has a LONG history in California.

As a surveyor in San Diego I found that La Jolla had a “covenant” that people of the Jewish faith could NOT purchase a home in La Jolla. This was as late as the 50’s. People in Coronado (home of the US Navy Pacific Fleet) could not sell to Asians.

A friend who served on the Lake Tahoe Lands Commission told me she found titles for land at Tahoe that said you couldn’t sell property to Black people…..and the beat goes on.

Let’s not forget the post WW II GI Bill which allowed many white vets to become first time homeowners and generate family wealth but was not available to black veterans.