By Scott Thomas Anderson

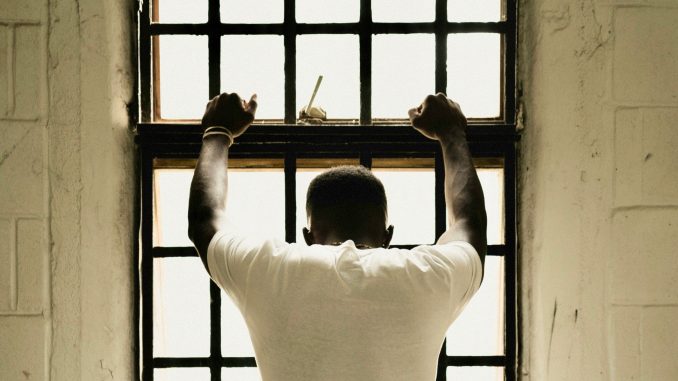

California prison authorities walked into the state capital over the summer hoping to get praise for adjustments they made to High Desert Prison in Lassen County, Pelican Bay Prison in Crescent City and a number of other correctional facilities; but instead found themselves getting raked over the coals in eye-opening fashion.

The exchange took place as the State Senate’s Budget Subcommittee No. 5.

Chris Chambers, Director of the Division of Internal Oversight and Research for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, was the unfortunate figurehead who had to weather the storm for nearly an hour. He listened as Caitlin O’Neal from the Legislative Analyst’s Office told the senators they were getting an update on where CDCR was with overhauling its system for investigating inmate complaints.

“Historically, these grievances were handled by staff at the prison, or within the parole system,” O’Neal said, “but in 2019, the Office of the Inspector General raised concerns that these cases were not being handled properly. There was poor investigatory techniques being used, and the people who were handling them showed signs of bias in favor of their fellow staff members.”

Amarik Singh, the Inspector General, was seated a couple of feet away from Chambers –and was about to elaborate on those determinations. Specifically, Singh was speaking to CDCR’s handling of reports around staff misconduct that came up through the grievance system.

“We found that, overall, CDCR’s performance was poor in 68% of the cases we monitored,” Singh told the senators. “Some issues that we identified were that CDCR failed to implement a cohesive and sustainable local inquiry process, which resulted in system-wide failures, confusion and frustration among staff. We also identified significant deficiencies and gaps in policy, which led to insufficient and incomplete inquiries.”

She added, “Some decisions about alleged misconduct were inconsistent with the evidence; there was untimely case processing; and failure by CDCR to communicate with our office, thereby denying the OIG the ability to effectively conduct its statutorily required monitoring.”

Additionally, Singh mentioned her team had completed an inspection of 24 randomly selected local inquiry cases that were closed-out within the last year.

“Of the 24 cases, [the Office of the Inspector General] rated the overall performance of the department poor in 21 on those cases – 88%,” she noted.

Singh finished her presentation by focusing on CDCR staff misconduct allegations.

“We found the investigators performed poorly in nearly 64% of those cases,” Singh detailed. “CDCR received poor ratings primarily because its investigators conducted biased investigations, conducted incomplete investigations, used poor investigative techniques and failed on ensure the confidentiality of investigations.”

For those familiar with the prison system, the stakes around that last finding – i.e. not staying tight-lipped around which prisoners have accused which guards of misconduct – can have dire implications inside a facility.

Chambers eventually made a statement about the need for CDCR to have ongoing conversations with various stakeholders and experts; and those opening remarks flew like a led balloon with State Senator Maria Elena Durazo.

“The part that’s most disturbing … ‘poorly, poorly, poorly’ – that’s all I heard coming out,” Durazo told Chambers. “Case after case, issue after issue, handled poorly … To think that, area after area, had such a high percentage of ‘handled poorly.’ I don’t understand. I’ve been on this committee for several years, and I’m hearing very similar to what we’ve heard a couple of years ago. You’ve got resources. What is going on here? We can’t keep coming back and hearing the same thing.”

Chambers did have a response.

“I would like to point out that there have already been a number of improvements made with respect to staff,” he pushed back, “both on the investigator side, to improve our performance, as well as on the locally designated investigators.”

Before leaving, Chambers added, “We received 183,000 allegations, of which 20,000 were thought to contain staff misconduct … To put it simply, I think the intended process, and the intended scope of the allegation decision index is not being met because the definition is just too broad. We inundate our processes, and we end up having this backlog … Our investigators are carrying well over 25 cases at any one time. That’s far too many to actively work.”

The other CDCR official at the hearing, Angela Kent, was better received. Kent updated the committee on new efforts to prevent sexual assaults of female inmates within the system. The committee’s prep documents for the hearing pointed out that “researchers have noted an overwhelming prevalence of sexual abuse histories of incarcerated women, with some figures suggesting that 86% of all women who are incarcerated have experienced sexual violence in their lifetime and 77% had experienced partner violence.”

The 2023 budget act had provided Corrections with a one-time fund of $250,000 to form a working group on preventing in-custody sexual assaults. Kent told the senators this group is now coming up with concrete plans.

Also addressing these efforts at the hearing was Amika Mota, the Executive Director for Sister Warriors, a nonprofit of formerly incarcerated women who are a key partner with CDCR in tackling the issue of female prisoners getting raped.

“We have made some progress since we started this collaboration,” Mota said. “At the town halls that we hosted 27 brave survivors testified to the abuse that they had suffered at the hands of a gynecologist at [California Institute for Women in Corona] for over a decade. Shortly after those town halls, this doctor was finally removed from the yard.”

Regarding the Lassen police not investigating,cases properly,My husband was attacked by our next door neighbor using brass knuckles resulting in 4 broken ribs,acollapsed lung since

heprotected his head,(which was the place he desperately was aiming for).we were careflighted to Renown(we both had covid)I got out a day earlier and feared my neighbor) we decided to file a police report when he got home. we went to the station where we talked to a female officer. she took notes, made copies of the hospital discharge papers took photos,told her we have surveyance video at our motel,She took notes,said she would investigate(,with all the evidence we had,I expected them to arrest him immidiatly) we weren’t given a case number,or her card.that was the last we heard.