![07news[a]](https://chico.newsreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/07newsa-678x381.jpg)

By by Amelia Wu and Helena San Roque (for Cal Matters)

This story was produced by the CalMatters College Journalism Network, a collaboration between CalMatters and student journalists from across California. This story and other higher education coverage are supported by the College Futures Foundation. For more info, visit calmatters.org.

When San Jose State anthropology professor Elizabeth Weiss tweeted a picture to celebrate returning to campus in September 2021, it caught the attention of Assemblymember James Ramos, a Democrat from San Bernardino and the Legislature’s first and only Native American member.

“So happy to be back with some old friends,” read the caption of Weiss’ tweet, which included a photo of her holding the skull of a Native ancestor in front of boxes of other remains.

For Ramos, a member of the San Manuel Indian Reservation’s Serrano/Cahuilla tribe, the caption was an example of the lack of respect for Native history in California. The boxes in the photograph’s background were a reminder of the vast collections of Native remains and artifacts still being held illegally in California’s public university systems.

The post prompted Ramos to request an audit of the California State University’s repatriation progress—the act of institutions giving back remains and artifacts to Native tribes as required by state and federal laws passed as far back as three decades ago.

“To find that we’re still in the year 2023 and that hasn’t happened is really daunting to find out how we move forward,” Ramos said. “But now that I’m in the state Legislature, we have a stronger voice to ensure that people truly understand that this is something that needs to get done.”

When the Cal State audit published in June 2023, results were similar to an audit of the University of California conducted three years prior—a lack of policies, urgency and staffing meant neither system complied with the California Native American Graves Protection Act of 2001 or the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990.

Cal State campuses collectively had returned only 6 percent of the 698,000 Native remains and artifacts to local tribes. UC campuses collectively returned around 35 percent of 17,000 human remains as of October 2023, according to UC spokesperson Stett Holbrook, with an additional 30 percent in the process of being returned.

At the time of the audit, two campuses stood out among their peers, however. UCLA returned 96 percent of its 58,200 items while Cal State Long Beach has given back 70 percent of its 9,000 items, the only campuses in their respective systems to return a majority of remains and artifacts back to Native tribes. Strong Native American voices along with allies in campus leadership and academic departments were factors that allowed both universities to lead their systems in repatriation progress. (Since the audit, UC Berkeley and three CSU schools—Sacramento, San Francisco and Chico—have stepped up efforts to make artifacts and ancestral remains available to tribes.)

In response to the state audit of the UC system, university officials released new policies governing repatriation efforts in December 2021. The six UC campuses with collections of more than 100 items are now required to have a full-time repatriation coordinator. UC also required campuses to submit budget proposals to fund full return of their collections to tribes and add more tribal members to committees that review repatriation requests.

As of June 2023, 12 of 21 Cal State campuses with collections subject to repatriation laws had yet to meet a 1995 federal deadline to complete an inventory of their collections, much less return remains or artifacts. Since the audit, Cal State has opened nominations for a new system-wide repatriation committee that aims for majority representation from Native American tribes, giving preference to California Indian tribal members.

Assembly Bill 389, introduced by Ramos and signed into law in October, requires Cal State campuses to fund the full expense of returning their collections, including full-time coordinators. The law also shifts the system’s relationship with Native remains and artifacts by prohibiting their use for teaching or research, a win for tribes who have accused universities in California of delaying repatriation so professors can continue their research. The law amounts to a major overhaul of the system’s repatriation process, ensuring funding shortfalls and research priorities no longer stall efforts.

At San Jose State, Weiss will resign effective May 29, 2024, as part of a settlement after she sued the university for barring her access to the campus’ skeletal collection following her post. The campus holds around 500 Native remains and 5,000 cultural items and completed its first repatriation of two remains and two cultural items to the Central Valley Yokuts tribe in March 2020, according to the audit.

“As I have said many times before, there is nothing wrong or controversial about this photo or the tweet,” Weiss wrote in a statement to CalMatters. “The photo shows my true love and respect for anthropology and the skeletal remains that make it possible.”

How UCLA returned nearly all remains and artifacts

When the state auditor reviewed the UC’s progress, UCLA stood out. Between 1996 and 2022, UCLA returned nearly its entire collection of Native remains and artifacts through 127 repatriations to tribes in California, Arizona, Hawaii and Utah. Most items in the university’s collections were unearthed during university and government construction projects, according to the director of UCLA’s Fowler Museum, Sylvia Forni.

“We don’t do anything special at UCLA that isn’t supposed to be done legally at other UCs and Cal States,” said Michael Chavez, who started as UCLA’s archaeological collections manager and repatriation coordinator this year.

Chavez, a Native member of the Tongva of the Los Angeles Basin, applauded a 2020 revision to the state’s repatriation law making it easier for non-federally recognized tribes to reclaim their ancestors and artifacts. He said his work largely involves listening to local tribes, federally recognized or not.

“We don’t decide for the tribe,” Chavez said. “We work in collaboration with the tribe and strongly defer to their opinion and position.”

Chavez credits the university’s 2020 audit results to the impact of his predecessor, former coordinator Dr. Wendy Teeter.

“[She] didn’t allow any obstacles to get in her way in the pursuit of repatriation,” Chavez said.

Despite limited funding and her multiple roles as a lecturer in American Indian Studies, a member of the UC’s Native American Advisory Committee and curator at the Fowler Museum, Teeter established a culture of welcoming Native communities during her 25 years on campus.

“We just broadened it to be more reciprocal in nature and more understanding that they had a lot to share with us and we had a lot to share with them,” Teeter said.

Beyond consulting with tribes on repatriation efforts, Teeter said Archaeology and American Indian Studies faculty assisted efforts by leading listening sessions and campus tours to strengthen relationships between the tribes and campus community. Having allies across academic departments was another key to UCLA’s success, according to Teeter.

Before campuses were required to estimate and fund the full cost of repatriation, Teeter said the vice chancellor of research would review funding requests to support her work, annually providing about $60,000. Additionally, she received financial help through applying for federal NAGPRA grants. Teeter is hopeful new policies at UC and Cal State will lead to sustainable funding for returning remains and artifacts to their tribal homes.

Since retiring from UCLA last year, Teeter now works with the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians as an archaeologist where she reviews development projects and mediates between the developer and the tribe.

Forni, Teeter’s successor at the Fowler Museum, said she’s committed to finishing the work led by Teeter and others.

“We think, at this point, [it] is 99 percent done,” Forni said.

Cal State Long Beach ‘a sacred site’

Puvuu’nga, the Native village that Cal State Long Beach occupies, is also a sacred site used for rituals and burials that connects tribes in Southern California and beyond. Since 1990, Cal State Long Beach returned 275 ancestral remains and 6,059 cultural items to three of the tribes local to campus, according to the June 2023 audit. The university is the only Cal State campus to have transferred the majority of its collection, at 70 percent.

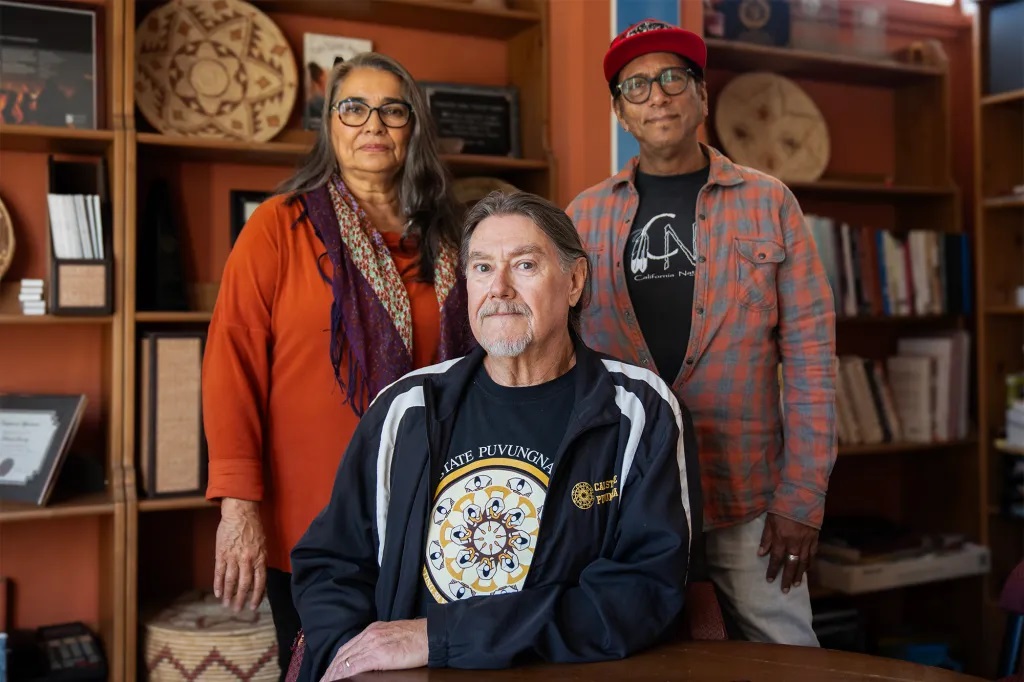

Founded in 1968, the American Indian Studies program at Cal State Long Beach is the oldest in California. Native history is central to the campus’ identity, unlike other institutions, said Dr. Craig Stone, professor emeritus of American Indian Studies and the former provost designee for Cal State Long Beach’s repatriation committee. The land the university occupies has ties to more than 20 tribes from the Gabrielino, Acjachemen, Luiseño, and Cahuilla bands of Native Americans.

“This is a sacred site, not just to the Tongva, Gabrielino people. This is a sacred site to anyone who’s been influenced by the Chingichnish spiritual philosophy,” Stone said. Chingichnish describes a deity and religion followed by Native tribes throughout Southern California.

The campus began repatriating the remains of Native ancestors long before the 1990 federal repatriation law, Stone said. Skeletal remains of ancestors found on campus during construction projects were given proper reburial.

“We interred in 1979,” Stone said. “So this is a commitment that people have heard of, know about, care about, and know when the law came into being, ‘Oh, yeah, we did that back in 1979.’”

A Cal State Long Beach student in the ’70s, Stone was one of 10 people on the student council who approached then-President Steven Thorn about the skeletal remains of a Gabrielino ancestor unearthed near the university during the construction of a sprinkler system.

“We went down there and we were gonna demand this and as soon as we got to the office he was like, ‘What’s going on guys? Let’s fix this, let’s review this ancestor,’” Stone said. “Which was interesting because people are not interested in fixing anything, so he was an ally right off the bat.”

Cal State Long Beach would go on to have more allies—including Professor Emeritus Marcus Young Owl, who was Stone’s colleague for decades and a current member of the Cal State Long Beach repatriation committee representing the anthropology department.

Young Owl, who describes himself as of Ojibwe descent, was a student and a founding member of the campus’ Indian Youth Council in December 1968. He started working as a faculty member teaching anthropology in 1987, replacing a professor who didn’t agree with repatriation, Young Owl said.

“I’m actually proud of the fact that the anthropology department was so willing to participate and have good relations with American Indian Studies,” Young Owl said.

For the remaining 30 percent of the university’s collection, the repatriation process has been slow. Stone attributes this to the previous lack of funding for a full-time repatriation coordinator and the months-long work of sifting through buckets of dirt and bones to identify ancestral remains.

A lack of funding for staff was a main issue cited in the audit of Cal State. Of the 23 campuses in the Cal State system, 10 reported a lack of sufficient funding to support the responsibilities that fall under federal and state laws, according to the audit.

The work of repatriation continues

Like UC before it, Cal State is now taking nominations until Feb. 2 to fill repatriation committees on campuses and statewide. Led by Adriane Tafoya, Cal State’s repatriation project manager, Cal State is working with the Native American Heritage Commission to host virtual trainings for campuses.

Cal State must adopt systemwide repatriation policies by July 1, 2025 and all campuses with collections must adopt campus specific policies by July 1, 2026. The system will also have to submit yearly progress reports on its repatriation efforts starting in 2024.

Since the audit, repatriation efforts on some campuses have ramped up, said Cal State spokesperson Amy Bentley-Smith. Since June 2023, San Francisco State has returned cultural artifacts to four tribes. This year, Sacramento State transferred 66,686 cultural artifacts and 498 ancestral remains to local tribes. In August, Chico State conducted the second-largest repatriation since 1990, repatriating 532 remains and 87,935 cultural items.

In October, UC Berkeley filed a report with the federal registrar, the first step to make available 4,400 Native remains and 25,000 Native cultural items for repatriation to California tribes. Once completed, it will be the largest repatriation for the campus that at one time had 11,000 Native ancestral remains.

“Tribal knowledge is key to repatriation, and we are so grateful to our tribal partners for working closely with us during this process,” UC Berkeley repatriation coordinator Alex Lucas wrote in a statement to CalMatters.

For Johnny Hernandez, the vice chairman of the San Juan Nation in California, repatriation is more than a legal procedure—it’s a matter of reuniting family members with their tribes after decades apart. Invited by Ramos to speak alongside other tribal leaders at a California State Assembly hearing on Aug. 29, Hernandez underscored the importance of allowing Native ancestors to finally rest in peace.

“There’s been a disturbance of grave sites on ancestral lands and remains of loved ones, our ancestors, being held without the opportunity to eternally rest in peace,” Hernandez said. “Imagine if it was your family, your ancestors, and their belongings that you hold near and dear that are owned and used under the guise of an artifact on display for the public’s learnings and teachings.”

Be the first to comment