Journalist captures sound, fury and lasting symbiosis in ‘Gun Comedy’

By Scott Thomas Anderson

Silver-shaded transitions from face to face. A camera’s eye that drifts behind turning wheelchairs and sliding bullet clips and heavy bootheels tromping through the woods. Graceful screen sequences that highlight survivors sharing their unguarded moments. “Gun Comedy” is Karlos Rene Ayala’s new exploration of struggle, passion, agency, redemption and tragic foreboding around the death-delivering steel that is everywhere in our nation’s life. And one of the storylines it follows is poignantly close to his own family’s struggles.

Ayala’s mother was pregnant with him when she fled El Salvador, escaping the numbing bloodshed of its civil war. Ayala – a writer, poet, photographer and videographer – says that he was largely raised in California by his brother, Memo, who taught him how to read and speak English, as well as an appreciation of the arts. “I would not exist as the person I am without him,” is how Ayala puts it.

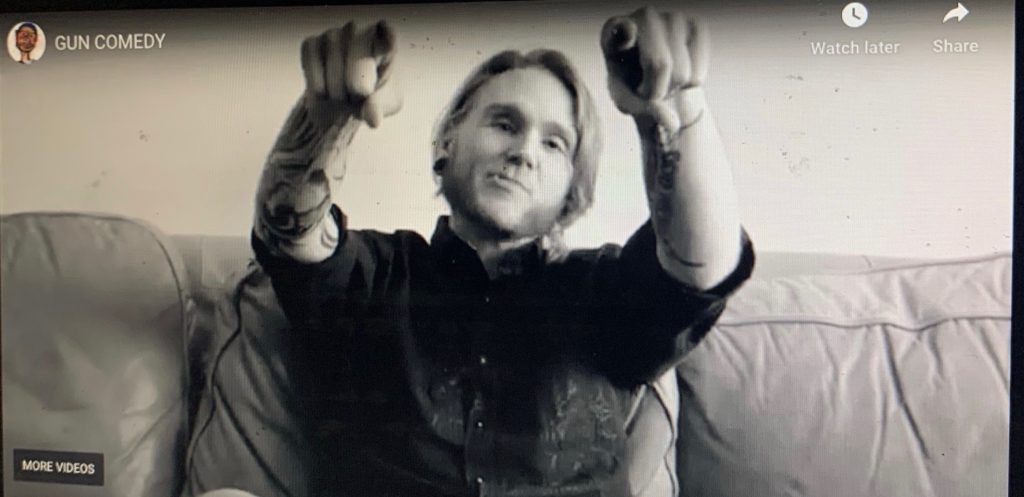

The first photograph that “Gun Comedy” opens on is a black-and-white image of Memo, at roughly 14, looking astute and coolly confident as he leans against a wall in his jeans and t-shirt. But there was a weight behind those knowing eyes: From a young age, Memo carried flashbacks of El Salvador’s urban carnage – and people disappearing in the middle of the night. Memo took his own life at the age of 38. It was the first time Ayala had ever seen his mother cry. The introductory words in “Gun Comedy,” from Ayala, are “for my brother.” The video then goes into motion as it settles on Mark Elhert, a man who survived a suicide attempt after shooting himself at point-plank range in the head.

The nexus between firearms and self-destruction is a through-line in Ayala’s film; and while those questions are the closest to his own story, they are far from the only ones he pursued. Ayala set out to map the vast grid of intersections between firearms and the human experience, particularly within the American story. He wanted his camera to be a nonbiased witness to the testimony of people who’d been both negatively and positivity impacted by guns. More than one of those tales involves someone who’s relationship to firearms started with the fear of having one pointed at them, and then progressed into confidence and self-empowerment by gripping the handle of one themselves. Yet from start to finish, “Gun Comedy” never avoids the shadow of the red, white and blue killing grounds that keep manifesting here from coast to coast.

“My work is about people, about us,” Ayala mentions. “It’s not entertainment, it’s understanding.”

Where the camera leads

To capture the vast breadth of the gun’s relationship to our nation’s psyche, Ayala not only interviewed an unlikely suicide survivor, he followed several women who’d been the victims of violence – one of whom, Emily Cotton, is confined to a wheelchair after being shot four times by her ex-husband – who later became firearm enthusiasts themselves.

Viewers who are used to the binary, hyper-politicized media-scape that seeks to code every story in context of a culture war may be surprised by “Gun Comedy,’ particularly as it introduces them to numerous Black women who are 2nd Amendment believers. One of those ladies telling her story is Shanara Sanders, who was accosted while leaving her Chicago home by two young men posturing as if they had a gun. In the film, Ayala follows Sanders as she took shooting lessons from Marchelle “Tig” Davis, a Black woman who’s a military veteran and gun expert trying to achieve a “life goal” of showing one million women how to use firearms. Tig got serious about this mission after enduring domestic abuse.

“A lot of these ladies are survivors, like me, and they just don’t know where to start,” Tig says of the training as Ayala films her. “They don’t know what to do to defend themselves. So, we’ve got to help them.”

She later adds, “We’ve taught all ethnicities; but I make sure I target Black women in my marketing, because there isn’t a whole lot of Black women in the gun industry. There aren’t a thousand of me, but there’s probably a thousand white male firearm instructors.”

Beyond self-defense, Ayala also captures another element of the American gun ethos by following a hunter named Felix Hernandez. While tracking animals with rifles and bows remains controversial, most men and women who hunt consider themselves wildlife conservationists, since the Pittman-Robertson Act channels the fees they pay into various habitat protection, management and restoration programs. In “Gun Comedy,” Ayala bypasses the politics of hunting, instead focusing his narrative eye on Hernandez as he stalks through the New Mexico woods with his Smith & Wesson 22LR in the lede.

In an understated but haunting scene, Hernandez shoots a rabbit and Ayala’s camera absorbs the strange glassiness of its eye as the life ebbs away.

“It was a very surreal moment,” Ayala recalls. “The camera stopped working as it was killed, which had never happened before. It just died as the rabbit died.”

‘Doomed captives’

“You have a 97% chance of not being shot if you move,” Chris Grollnek, an authority on mass-causality events, says midway through the film. “You need to overcome the fight, flight or freeze. Get up, and win, and get out – cause no one is coming to help you. There’s a new term that’s coined: ‘Doomed captives.’ So, when the police show up to a location, they are not coming to help the doomed captives. They’re coming to stop the shooter; because even the most basic-trained police officer that can put on the tourniquet, it takes approximately 60 seconds to stop the bleeding. So, if they stop the bleeding for you, the average active shooter can take four lives in 60 seconds.”

The threat of senseless slaughter is omni-present in “Gun Comedy,” specifically in form of the Robb Elementary School shooting that happened in Uvalde, Texas in 2022. Ayala uses that incident, which took the lives of 19 students and two teachers, as shorthand for the 700 mass-shooting incidents that would occur in the U.S. the following year. The Uvalde saga wasn’t just one of the most devastating school terror events in a decade, it’s also come to be viewed as one the greatest moments of shame for American law enforcement in a generation: That’s because an army of Texas peace officers waited in a hallway for over an hour, refusing to confront the shooter, and allowing him to continue assassinating helpless children at-will.

School surveillance footage of these officers standing by, doing nothing, amounts to the only footage in “Gun Comedy” that Ayala didn’t film himself. Yet, the director did bring his artistic touch to the images, speeding up the video feed in a way that conveys an almost cartoonish absurdity to the officers’ dumbfounding paralysis. This controlled footage fades in and out of the movie, always coupled with commentary by Grollnek, a former U.S. Marine and police investigator who’s considered an expert on school massacres and rampage shootings. Grollnek is sharply critical of law enforcement’s ability to adapt to mass shootings, beginning with Columbine High School in 1999 and carrying through the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in 2018. With the notable exceptions of the Gilroy Garlic Festival in 2019 and Covenant School in Nashville last April, law enforcement has failed at stopping these deranged mass-killers before the victim-count escalates.

In “Gun Comedy,” Grollnek saves his harshest analysis for the 300-plus officers who were at Uvalde and willfully stood down.

“And some of the feedback that came out, ‘Well, the police were nervous or scarred or unprepared, or under-prepared, because they had never been in a gun fight,’” Grollnek reflects, “that was some of the quotes. Well, I’ve got news for you, especially if you’re watching this, you know who else was never in a gun fight? That kid who took the lives of the 19 kids and the two teachers.”

“Gun Comedy” was released just as a case called United States v. Rahimi was being heard by the Supreme Court. Rahimi challenges the federal law prohibiting someone from having a gun if they’re subject to a domestic violence restraining order. The case is seen as part of a broader effort to weaken the legal underpinnings of “red flag” laws, including those that would stop mentally ill individuals from getting their hands on guns. According to American Progess.org, two-thirds of all mass shootings between 2014 and 2019 occurred during a domestic violence incident. The killer in the Robb Elementary School incident had, in fact, shot his own grandmother in the face prior to going to the campus.

United States v. Rahimi is being brought by Zackey Rahimi, a Texas man who authorities say was involved in five different gun crimes between December 2020 and January 2021: Those reportedly included shooting at a stranger in a road rage incident, opening fire on a different person’s house after Rahimi was incensed by a social media post, and pulling a pistol out inside a fast-food restaurant and popping rounds off when a friend’s credit card was declined. Rahimi was arrested for, and ultimately convicted of, the federal crime of having guns while being subject to a domestic violence restraining order. On Nov. 7, the Supreme Court justices heard oral arguments by Rahimi’s lawyer and opposing attorneys from the Biden Administration.

While the High Court hasn’t issued a ruling yet, Chief Justice John Roberts seemed highly skeptical of the argument being made by Rahimi’s counsel, Matthew Wright.

“You don’t have any doubt that your client is a dangerous person, do you?” Roberts asked from the bench.

“Your Honor, I would want to know what ‘dangerous person’ means,” Wright responded.

“Well, I mean someone who’s shooting at people,” Roberts went on, “that’s a good start.”

The darkest passage

Ayala started making documentaries ten years ago, eventually debuting his third film, “Brother Leroy,” a heartfelt portrait of a late Sacramento resident named Leroy Dauphine. Leroy was a retired janitor, who loved to laugh and dance, and who drove an insanely decorated car around Broadway Avenue. He was the only Black member of a local Romanian church. Ayala’s 20-minute exploration of the man’s twilight years remains a moving snapshot of a one-of-a-kind personality around the capital.

The path to making “Gun Comedy” began with Ayala’s girlfriend helping him apply for grants from the National Endowment of the Arts and the Sacramento Office of Arts and Culture. The socially intuitive filmmaker then worked on the project every single day for a year.

“Originally, I set out to interview about 13 people, and have about that many in the documentary that would be survivors of gun violence, or enjoy guns in a sporting fashion – I wanted to do a whole amalgam of people impacted by guns, positive or negative,” Ayala remembers. “I still think I did that, but I feel it’s a little more about mental health; and about the things people think they need to do to survive.”

A one-man show, Ayala handled the lightening, camera shots and interviews entirely by himself. He’s a journalist who has always loved talking to strangers and getting to know people from different walks of life, so the biggest challenge was on the mechanical and technical end of things. Ayala’s fluid proficiency with the camera, and ability to make subjects comfortable and connected, shine in almost every minute of “Gun Comedy.”

“All these stories are kind of bleak,” he acknowledges. “As far as the biggest surprises, I don’t know, I hate to color it with my progressive standpoint. You know, none of the people I interviewed were crazy. I can see why you would own a gun. I can see how California has a little bit of a stick up its ass about firearms. There are so many people with them, that it almost feels like you have to have one, which is like a fucked-up Catch 22. But, hanging out with these people, they’re not what you see portrayed in most firearm stories, you know, about this crazy, Right Wing, gun-hording guy who’s ready for the revolution – you’re January 6-type folks – I didn’t meet anybody like that. Everybody was very sweet, responsible and wanted to bring you in and teach you everything they could.”

One point of confusion that Ayala has dealt with since “Gun Comedy’s” release involves an interview subject referred to in the film as ‘Genny.’ Remaining anonymous, Genny is a politically estranged gun owner who witnessed a violent crime when she was young. Throughout the movie, she offers meditations on how firearms are conquering the American psyche in ways that the authors of the Second Amendment could never have dreamed of. To shield Genny’s identity, Ayala replaced her voice – somewhat jarringly – with that of a little girl. However, some viewers have suspected Genny’s words are actually Ayala’s own thoughts and standpoints.

“Genny is not me,” he stresses.

Ayala’s emotional core may not be found in Genny’s voice, but that doesn’t mean it is not in the film. Mark Elhert is the very first face – after Ayala’s brother – and the very last face, that the documentary shows. Elhert describes in tense, methodical detail the tunnel-like state of mind he found himself in on that afternoon that he shot himself in the head. While some astoundingly successful surgeries have left Elhert’s head and face looking normal, the point-blank blast robbed him of his eyesight. In “Gun Comedy,” Elhert talks directly and coherently – often eloquently – about his revelations around mental health awareness, all of which came as he was learning to live an entirely new existence as a blind person.

In the late stages of the documentary, Elhert says he will never attempt suicide again, not only because of the hard-fought lessons he’s learned during his recovery, but because he now understands the trauma that his suicide attempt inflicted on his brothers.

“I can’t image what was going through their heads, what they thought had happened to me,” he admits in the film. “Even worse, when my little brother got to the hospital, he was the first person to know it was a suicide … I wanted people who were walking out of my life to feel guilt and regret, but I didn’t release the impact I was going to have on the people who weren’t walking out of my life – the people who really do truly love me, my brothers.”

After everything Ayala had gone through losing Memo to suicide, Ehert’s revelation hit him somewhere deep.

“It felt like was listening to my own brother talk to me and ask for forgiveness,” says Ayala. “It was very heavy. Mark is blind, so he has no idea I was crying while I filmed that moment.”

Scott Thomas Anderson is also the writer-producer for the true crime podcast series ‘Trace of the Devastation’

Be the first to comment