By Rya Jetha, Jeanne Kuang and Jeremia Kimelman (for Cal Matters)

CalMatters is an independent public journalism venture covering California state politics and government. For more info, visit calmatters.org.

California is full of food, yet scarred with hunger.

Despite the state producing nearly half the country’s fruits and vegetables, one in five Californians are food insecure, meaning they have limited or uncertain access to adequate food. Food insecurity does not necessarily cause hunger, but hunger is a possible outcome.

People experience food insecurity in different ways. Some families may only eat lesser quality food, while others may simply eat less.

Food insecurity can have long-term physical and mental health effects. Research shows that food-insecure children can experience developmental delays and have trouble learning language. Children also are more likely to fall sick, recover more slowly, and be hospitalized more often if their access to food is inconsistent, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. Food-insecure adults face higher rates of obesity, chronic illness, anxiety and depression.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought sharper awareness to hunger in California, as many Americans experienced food insecurity for the first time. In the last year, record inflation drove food prices up 4.5 percent. Then in April, an influx of federal food aid from the pandemic dried up. The state has tried to take advantage of federal programs that provide food aid and expand the pool of who is eligible for help. Still, some warn that the number of food-insecure Californians will rise far beyond 20 percent in 2023.

The situation varies widely depending where you live—from as low as 17 percent to as high as 44 percent across the 58 counties—and not always where you might expect. Butte County is at 22 percent, while Colusa is the highest at 44 percent.

Here’s a look at how big the problem is, why it’s challenging to get help to those who need it and some potential solutions to hunger in California.

What is the problem?

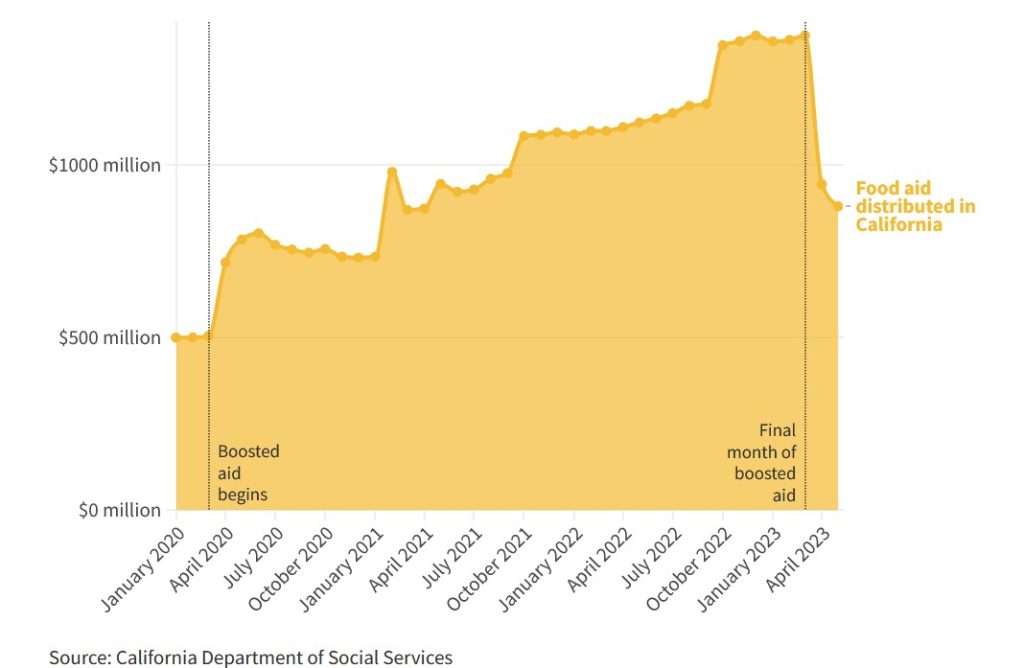

When the pandemic struck in 2020, recipients of CalFresh, California’s version of food stamps, were given the maximum benefits available for their household size. Advocates theorize that may have contributed to a steady growth in enrollment; total payments to California families rose from $505 million in March 2020 to $1.4 billion in March 2023.

In May 2019, before the pandemic, the average Californian receiving food stamps got $132 a month; In May 2021, when benefits were boosted during the pandemic, the average Californian receiving food stamps got $214 a month.

Those emergency allotments ended in March, reducing benefits to 5.3 million Californians by a total of nearly $500 million a month. For some single-person households, CalFresh benefits dropped from $281 to as little as $23 a month. In May, the average Californian receiving food stamps got $179 a month.

The extra benefits maintained the number of food insecure Californians at 20 percent during the pandemic. However, that number is expected to rapidly rise this year.

Since March, Californians have turned to their local food banks in record numbers. Instead of functioning as sources of emergency aid, food banks say they are becoming long-term supermarkets for Californians facing food insecurity.

March and April were among the busiest months ever for the Sacramento Food Bank & Family Services. Before the pandemic, the food bank served around 150,000 people per month. Since March, it has averaged more than 270,000 people each month.

The statewide food banks association is warning of a “catastrophic hunger crisis” this year, and it appears to be coming true.

How far does food aid go in California?

State government’s primary way to help low-income families afford food is CalFresh. Qualifying recipients get money each month on an Electronic Benefits Transfer card, which is similar to a debit card, and can spend it on food items at grocery stores and some farmers markets.

How much each family gets depends on their household size and their income. Benefit amounts are set each year by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and are based on nationwide cost-of-living measures. That can result in benefits that don’t always account for the way food prices rise locally.

The federal government has boosted benefits during emergencies, such as the Great Recession and the pandemic. In October 2021, it also overhauled its formula for calculating benefits, resulting in a significant hike during record inflation.

California enrolls fewer in aid

A little more than 70 percent of those who qualify for food benefits are actually receiving them. That participation rate has frustrated advocates because it leaves valuable federal funds on the table that could feed more Californians and boost the state’s economy.

The reasons are complex and varied: Geographic and ethnic diversity makes some poor Californians difficult to reach. Many immigrants fear signing up could hurt their citizenship chances. It can be hard to apply for seniors or those who don’t speak English. And college students face a byzantine set of special eligibility rules.

Another major challenge is that California’s 58 counties administer food benefits, rather than the state government, creating a variety of application processes statewide. California is one of only ten states that use a county-based system to distribute the aid.

That means some counties enroll far more eligible families than others.

In 2020, the latest year for which the state has data, Los Angeles County had nearly 80 percent of its eligible population receiving the benefits. Contra Costa County, meanwhile, had enrolled about 64 percent. That year, five other counties, including relatively affluent San Mateo and San Luis Obispo, had fewer than half their eligible residents receiving benefits.

Red tape can get in the way

Many college students, immigrants and older Californians have particular trouble accessing food assistance. There are additional eligibility rules that can affect those groups, which complicate an already lengthy application.

Food assistance advocates say counties should be doing more to help qualified residents get on CalFresh, but beleaguered counties say they’re underfunded and understaffed. The state—following federal regulations—only pays county social services agencies based on how many people receive aid, not on how many apply. Critics say this means counties are not incentivized to help vulnerable groups go through the application process.

Take, for example, mostly rural Yolo County just west of Sacramento. It has the state’s highest poverty rate in part because it is home to tens of thousands of college students at UC Davis.

After conducting extensive outreach to students and campus groups, the county’s Health and Human Services agency received double the applications each month for CalFresh from 2016 to 2021, said Nolan Sullivan, its director.

Despite that, CalFresh households rose only 21 percent and the county’s funding went up only 6 percent in that time. That’s because college students have high rejection rates for food stamps, because the rules for them are so complex.

But getting more people on food aid includes walking them through the application, which is a time- and labor-intensive process.

And when students ultimately are denied at the end of the process, Sullivan’s department doesn’t get any extra funding for the work it took to help them apply.

“It penalizes us for doing outreach to try to get students on,” he said. “I want every student to apply that thinks they might be eligible. But we get overwhelmed.”

What changed during the pandemic?

Though the COVID-19 pandemic has largely receded, the spike in need that began with the health emergency hasn’t. Enrollment in food stamps has steadily grown. CalFresh participation climbed to more than 3 million households—more than 5.3 million people—earlier this year before dipping slightly.

The growth in food stamps recipients may be due in part to the boosted benefits that ended this year and several more flexible, but temporary state and federal rules that made it easier to apply or qualify for CalFresh. Some of the temporary changes that are scheduled to lapse in 2024:

• Interview requirements: Federal regulations require applicants and CalFresh recipients who are renewing their benefits to interview with a county welfare office to verify their application. California counties vary on whether they offer a phone option or require in-person interviews, and advocates say failing to clear this hurdle is one reason eligible recipients often lose access to aid and reapply, a phenomenon experts call “churn.” During the pandemic, however, applicants were not been required to interview if counties can verify their identity other ways. This relaxed rule is in place until April 2024.

• Signature requirements: All CalFresh applications must be signed, either physically or through a telephonic recording. Another relaxed requirement in place until April 2024 allows an applicant to simply verbally attest to a county welfare worker that their application is correct.

• College student access: College students are typically barred from food stamps unless they meet one of a dozen complex exceptions. During the pandemic, a much more flexible eligibility rule allowed many more students to qualify for aid. But that rule ended in June, and those who signed up under it will get a year of food stamps before they are either cut off or must find another way to qualify.

What solutions are being tried?

California will begin a test next year in select counties that increases the minimum monthly CalFresh benefit from $23 to $50 per household and that supporters hope will go statewide with a higher amount.

In addition to a longstanding nutrition program for expecting mothers or moms with young children and a universal school meals program, lawmakers are continuing to expand California’s nutrition safety net. The California Nutrition Incentive Program runs a variety of programs to help CalFresh recipients buy healthy food. At 270 farmers’ markets across the state, food aid recipients get as much as $10 in matching money—meaning they have at least $20 to spend every week on fresh fruits and vegetables.

Policymakers recognize that CalFresh recipients predominantly shop at big-box stores and supermarkets. So the state recently funded a pilot, based on a model pioneered by Massachusetts, that allows recipients to get money rebated directly back on their EBT cards after buying fruits and vegetables at authorized grocery stores. Gov. Gavin Newsom just signed into law a bill for the state to seek federal waivers so that recipients can buy hot and prepared foods.

Challenges of scale, funding and inclusiveness still remain for California’s food aid programs. Continuing budget deficits could mean a shrinking of resources available to documented and undocumented food insecure Californians. With future budget surpluses, however, policymakers will be able to expand existing programs and consider new, research-based programs to end hunger in the state. What else could be done?

• Increase public funding to food banks, to buy more from small farmers and distribute the produce to all.

• Expand access to undocumented: Beginning in 2025, California will be the first state to issue food stamps to undocumented immigrants who are 55 and older. Advocates are calling for this policy to be expanded to all of California’s 2.3 million undocumented people and beyond to drastically reduce hunger in the state.

• Provide produce prescriptions: Imagine going to the doctor, who gives you a prescription to buy fresh fruits and veggies, and then getting reimbursed by your insurance provider. “Produce prescriptions” are already being tried in Stockton and Los Angeles, and advocates are calling for its large-scale expansion.

Be the first to comment