What’s the theme of 2022 for Butte County?

Maybe it’s recovery. Illness and death of the COVID-19 pandemic greatly diminished early in the year, leading state and local officials to lift most restrictions. People are back to hanging out with each other and arguing over politics.

Maybe there is no theme. In a county that’s suffered one catastrophe after another in recent years, not having an overarching trauma to define us is a welcome relief.

What follows are the 10 topics that rose to the top of the stories the CN&R told over the past 12 months.

City manager out

Thursday, March 10, Chico City Manager Mark Orme joined Mayor Andrew Coolidge for a state of the city videoconference presented by the Chico Chamber of Commerce. The next afternoon, Orme and the City Council gathered on the second floor of the Old Municipal Building for a strategic planning session.

Little did he know that these two events would cap his nine-year tenure at City Hall. Orme was halfway out the door at a special council meeting Coolidge called for March 23 and officially out of a job at a second special meeting March 25, having resigned in lieu of termination.

The council appointed Police Chief Matt Madden as interim city manager without advising him in advance (see “What Were They Thinking?” page 18). Within a week, the city started searching for a new interim city manager—and the council hired Paul Hahn, retired county chief administrative officer, April 13 to bridge the timespan to a permanent city manager.

The CN&R, among others, speculated that council conservatives had their eye on Mark Sorensen, a former Chico mayor working as city administrator in Biggs. Sorensen got the gig June 30—the day after Madden announced his retirement from Chico PD after 30 years in law enforcement. Orme recently interviewed for a city manager position in Florida.

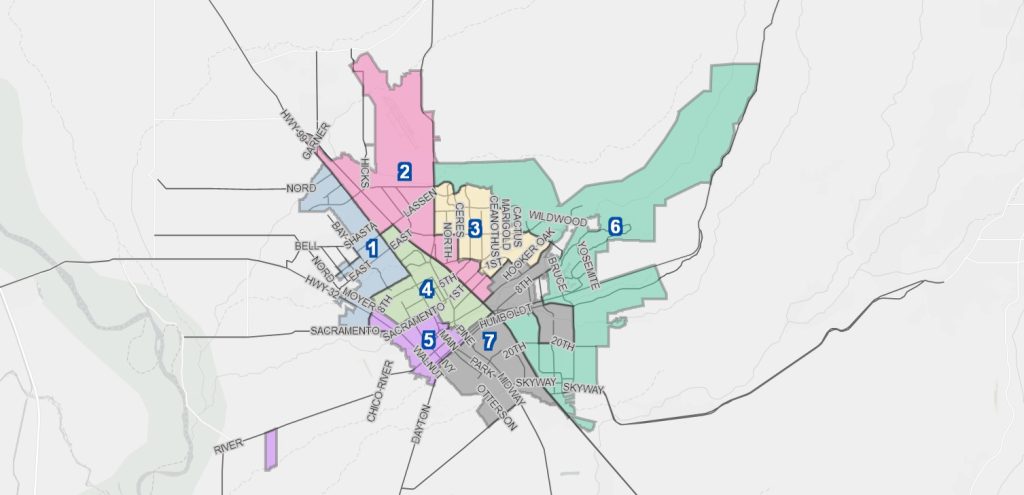

Redistricting fallout

With 2020 census data released last year, legislative bodies at state and local levels began the once-in-a-decade exercise of redistricting. Stakes are always high—balances of power hinge, in large part, on the distribution of voters.

The relatively rural North State districts for Congress and state Assembly remained functionally the same as safe seats for Republicans. Within Butte County, however, lines shifted significantly for the Board of Supervisors and the Chico City Council, while the Chico Unified School District (CUSD) and Chico Area Recreation and Park District (CARD) drew districts for the first time.

The county’s redistricting proved the most contentious. On a 3-2 vote, supervisors chose a map that created two western agricultural districts but also cut into Chico four ways. Chico Supervisors Debra Lucero and Tami Ritter, the opposing votes, alleged gerrymandering—asserting that the new map packed Democrats into a single district to get more Republicans elected.

Local Democrats mounted a referendum drive but failed to get enough signatures. Ritter handily won reelection in June, while Lucero lost the seat for the new District 2 to Chico Police Sgt. Peter Durfee.

The City Council adjusted the initial districts it drew for Chico just two years earlier. Ultimately, council members went with a map put forward by citizen Nichole Nava, who ran for a seat in November, that also stirred complaints of gerrymandering (though no push for a referendum or legal challenge). The 5-2 vote had dissent from Alex Brown, who opted not to seek reelection, and Dale Bennett, a council appointee whose short-term election in November fell under the previous configuration.

In the final tally, City Council race results showed Vice Mayor Kasey Reynolds winning a second council term; tenants’ rights activist Addison Winslow defeating Nava; businessman Tom Van Overbeek also securing, and Bennett retaining his seat.

CUSD’s foray into districting also sparked divisiveness, notably from Chicoans who opposed the school board majority following state health department mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Politicization carried over to the election, in which two trustees (Thomas Lando and Matt Tennis) faced off in one district and one trustee (Kathy Kaiser) gave way to a colleague (Eileen Robinson) rather than compete in their district. Lando and Robinson secured new terms; Rebecca Konkin won a duel of newcomers in the western, rural district.

Drought: Year 3

On the eve of 2022, Californians were drenched and hopeful. The 2021 holiday season saw record-breaking amounts of rain and snow for the state, but those December storms did not carry over into the the new year. In fact, so far, 2022 has been California’s driest year on record. Most of last December’s gains in the Sierra Nevada snowpack quickly melted and evaporated away.

California’s current drought began in early 2020; state and county emergency orders have been in place since the summer of 2021. In Butte County, the modest overall amount of moisture over the past year has only slightly improved the situation, moving most of our area from “exceptional” to “extreme” drought.

In March, after Californians fell short of Gavin Newsom’s 15 percent voluntary water-reduction goal, the governor issued an executive order for water suppliers to implement drought contingency plans. The measures largely impacted industrial landowners, but domestic users, in addition to being required to implement common-sense conservation practices, were instructed to water lawns no more than twice a week.

Persistent drought conditions led to increased wildfire danger (though thankfully no major conflagrations for Butte this year) and shrinking reservoirs. As of Nov. 23, the water level at Lake Oroville was at 662 feet elevation with storage about 28 percent of capacity (56 percent of historical average). There also has been been an increasing number of domestic wells going dry in the county’s lower elevations. Last year, 44 dry wells were reported. By June 21, that number already was 72, according to an August Drought Emergency Update by Butte County Office of Emergency Management.

In June, the Butte County Department of Water and Resource Conservation released the results of a Drought Impact Analysis Study. The report outlines myriad ways drought has affected this region, including Butte and surrounding counties’ increased dependence on tapping into precious groundwater reserves. In 2021, extraction from the county’s two major subbasins—Butte and Vina—exceeded sustainable yields by 74 and 10 percent, respectively.

COVID’s peak and descent

COVID-19 shaped 2021. This year, Butte County followed the country (and much of the world) in pivoting to lesser urgency as the pandemic peaked in January and variants of the virus proved more contagious but less deadly.

Jan. 10 marked COVID’s crest locally with 395 new cases reported that day and a seven-day average of 286. Twenty-eight county residents lost their lives to COVID in January. Flash forward 11 months: County Public Health reported no cases Nov. 22, with a seven-day average of eight, and no deaths since Oct. 16.

The omicron variants that emerged this year spread more readily but caused milder symptoms than previous variants. As a result, government officials have loosened restrictions, such as eliminating mask mandates. Butte County, Chico and the state have ended, or are in the process of ending, their emergency declarations. Businesses reopened fully. Schools returned to full in-person learning after utilizing remote instruction or hybrid options.

Local health officials stress that the pandemic is not over and encourage precautionary measures such as testing before and after gatherings with elderly, vulnerable people and wearing masks for large public events.

Still unsettled

Homelessness in Chico has dominated public discourse for roughly a decade now, shaping city elections and fomenting bitter divisions among the citizenry. The City Council’s priorities, policies and plans—many of questionable substantive value and legality—have shifted dramatically in the past few years, but 2022 kicked off with the most significant event to date in the long-running drama: the January settlement of the Warren v. City of Chico lawsuit.

The outcome was a victory for homeless advocates for several reasons. The agreement with its monetary award ($650,000 to Legal Services of Northern California and $12,000 to the eight unhoused defendants) affirmed claims the city’s enforcement policies—rousting encampments without shelter alternatives—were unconstitutional. Furthermore, the city had to implement new camping enforcement rules and ensure there was shelter available before forcing campers to move. All of these efforts would include input and oversight from Legal Services of Northern California (LSNC) for the next five years.

This led to the opening, in late April, of the Chico Emergency Non-Congregate Housing Site (commonly referred to as the “Pallet Shelter”) next to the Silver Dollar Fairgrounds. The facility features 177 units of 64 square feet, potentially providing shelter for 354 people, and provides daily meals and on-site workers to connect residents to needed services.

Still, the site has been a source of controversy, even before it opened. Some homeless advocates objected to the city contracting with the Jesus Center to manage the site, saying the faith-based nonprofit lacked experience with harm-reduction practices and that rules the organization implemented created barriers for potential guests. Complaints continue, with some social workers and unhoused people saying the shelter remains too difficult to get into, though it’s never been at capacity.

Meanwhile, the city continues to play whack-a-mole with homeless encampments, albeit now under the scrutiny of LSNC; disagreements over the city’s adherence to new rules have landed the parties back before a judge multiple times. With Chico voters passing a so-called quality of life measure, which expands public nuisance codes to city-owned properties (see “What Were They Thinking?” page 18), and a conservative-heavy council still in place, the issue seems still unsettled.

Roe, Roe, Roe the vote

June 24—the day that the United States Supreme Court voted 6-3 to overturn the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling—will forever be remembered as a day of infamy for advocates of body autonomy and the right to choose. Not only did the decision remove constitutional protections for abortion, it exposed the fragility, and cast doubt on the future, of civil rights for LGBTQ people, same-sex marriage laws and, some say, democracy itself.

People swarmed to the streets across America to protest this decision, including in Chico. Hundreds gathered in the Chico City Plaza on May 3, when the draft decision leaked. County Supervisor Debra Lucero, City Councilwoman Alex Brown, congressional candidate Max Steiner and former congressional candidate Audrey Denney were among the masses, whose collective voices could be heard across the street in City Council chambers during the meeting that night. More demonstrations followed.

The voice of a majority of California voters also was heard, loud and clear, on Election Day (Nov. 8), when more than 65 percent said yes to Proposition 1—a ballot measure amending the state constitution to prohibit the state from interfering with or denying an individual’s reproductive freedom while ensuring the right to an abortion and contraceptives. Similar measures were approved in Vermont and Michigan, while Kentucky, Kansas and Montana rejected anti-abortion initiatives.

Chico’s first local sales tax

The city is short on money—that’s been a familiar refrain since the Great Recession, when municipal leaders started addressing structural budget deficits by scaling back services and cutting employees. Roads have deteriorated to a paving condition index of poor; other infrastructure maintenance and Bidwell Park remain underfunded.

Ahead of the 2020 election, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a progressive-majority City Council failed to advance a half-cent sales tax increase. The current conservative majority voted to place a 1-cent increase on the November ballot despite high inflation, rising fuel costs and individual members’ stances regarding tax increases.

A coalition spanning the political spectrum, from former mayors to the Chamber of Commerce, campaigned on behalf of the tax measure, projected to add $24 million a year to city coffers. (For reference, the city’s 2022-23 budget totals $211 million—allocating $97.4 million to operations, from the general fund, and $113.6 million to improvements, from the capital projects fund.)

Voters approved the tax increase with 52.7 percent in favor.

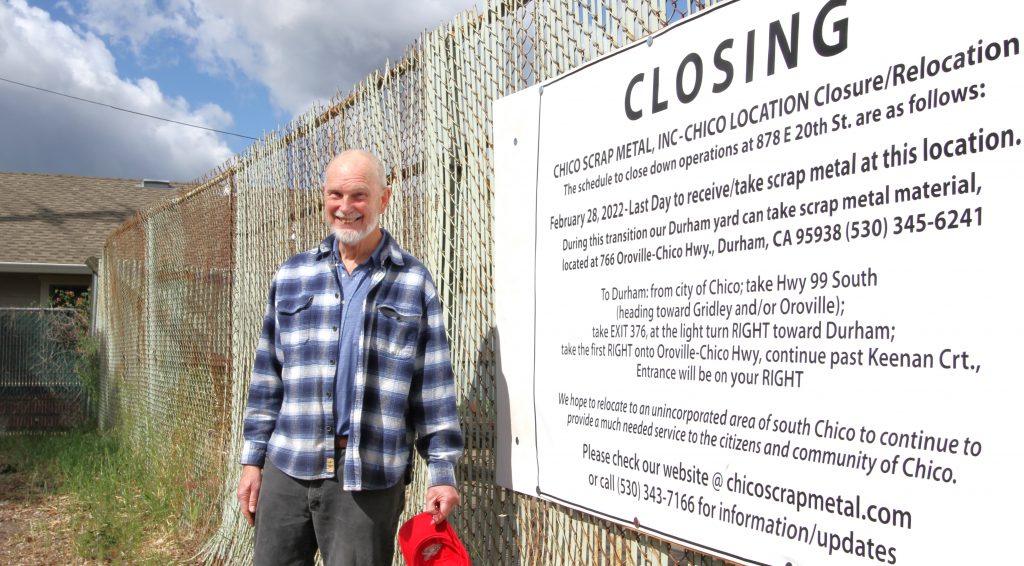

Finally junked

For 16 years, the saga surrounding Chico Scrap Metal has played a major role in city politics and resulted in all kinds of drama. The business was first ordered to move from its E. 20th Street location by the city in 2006, as directed in the Chapman/Mulberry Neighborhood Plan, but the business refused to go without a fight. The ensuing years have been filled with extensions and reversals from the City Council, legal battles and lots of twists and turns, including the city suing a sitting council member, Karl Ory, over his involvement with advocacy organization Move The Junkyard.

Now, at long last, it appears to be over. CSM stopped accepting recycling last year, citing difficulties resulting from the long fight; and on Feb. 28, the business shut down its operations for good.

But is it really the end? Even as the property closed, co-owner Kim Scott said the business intended to keep fighting in court to get the city to help pay roughly $4.5 million for the move (her estimates for new property, infrastructure and permitting). The Scott family’s scrap operations continue at sites in Durham and Oroville.

And there’s the matter of the property left behind, which is still owned by the Scotts and could be valuable to new buyers—if it’s properly cleaned up. A historical auto-wrecking business operated on the property for decades even before CSM occupied the site. The Department of Toxic Substances Control detected lead, chromium and other dangerous contaminants there in 2007.

Re-open for business and fun

The only certainty during the COVID-19 pandemic was change, especially for those who own local businesses.

When the economy reopened, residents saw a new lay of the land in Chico. Some businesses kept their COVID adaptations such as outdoor seating and curbside pickup. Others showed up in new locations (e.g., Music Connection, the Roost, Om on the Range) or showed off newly remodeled digs (Cafe Coda, Naked Lounge). Some (Maltese Bar & Tap Room, Alpaca Bob’s, Blue Room Theatre, et al) were forced to shut their doors for good.

As the pandemic receded and locals slowly started to return to public gatherings, familiar entertainment options remained on the calendar—plays from most of the community theaters, concerts at the El Rey and Senator theaters and Chico Performances shows at Laxson Auditorium. The Sierra Nevada Big Room has yet to re-open for live shows, but there are a handful new music venues that have blossomed, including the Mulberry Station brewery/pizza joint; Om on the Range; the lounge at Gnarly Deli; Naked Lounge’s new stage; and the new indoor addition at Secret Trail Brewing Co.

‘No Hotel’ protests

California Park residents learned three years ago, during the week of Thanksgiving no less, that a developer planned to build a four-story hotel on the southwest side of their neighborhood. The parcel borders Bruce Road between Highway 32 and Sierra Sunrise Terrace—the latter being the vehicular access point for not only the hotel but also a cluster of residential communities for seniors.

Members of homeowners’ associations within the vicinity coalesced into a group called No Hotel California Park to oppose the project. Designed as a TownPlace Suites of 112 rooms on 4 acres, the Marriott hotel reached the city Planning Commission this summer.

Commissioners denied the application for a use permit on a 3-2 vote with two absences. But the developer appealed to the City Council, which overturned the Planning Commission’s decision. The council’s action, on a 5-1 vote (Kasey Reynolds dissenting, Alex Brown absent), left the door open for a further appeal by referring the project to the Architectural Review and Historic Preservation Board.

And this paper shamefully endorsed that sales tax increase which will hit poor and working people the hardest. And for what? So that city bureaucrats and other city employees can receive crazy pensions that we can’t afford and the sales tax increase won’t change that, so the city council beholden to those special interests will do all they can to continue to raise taxes and take on debt.