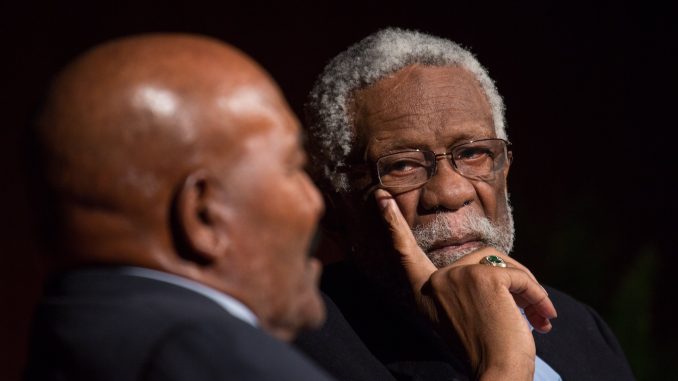

Philosophically I was opposed to racism being part of the atmosphere. I did what I thought I could do to help change it, or at least expose it. You can never hope to solve a problem until you recognize it as a problem.—Bill Russell, NBA legend, Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient and civil rights icon

I dedicate this column to both my hero Bill Russell, and my friend Cory Himp Hunt, a local poet, musician and KZFR (90.1FM) colleague who recorded a conversation for the radio with me about the life of Russell (who died July 31) as well my own life of missteps, travails and regrets in matters of race. Cory believes it’s important for people to tell the personal stories that transformed their views of racism for the better. I’m humbled to have presented a snippet of my life’s story as a testament on how we can address racism and bigotry when, and where, we see it.

I would like to say, as Russell could, that I’m a lifelong advocate against racism. I can’t. At least not until after the last time I used the N-word in public. It was in 1991 at the Torch Club in Sacramento attending a Sacramento Blues Society show. A friend asked me to point out someone in the crowd. Laughing, I gestured to my right spouting, “He’s the N-word over there.”

The words were no sooner out of my mouth when a gray-haired African-American man standing two-feet in front of me slowly turned around to lock eyes. Shaking his head in disgust, he gave me the dirtiest look humanly possible. His disgruntled demeanor telegraphed that my sheepish, “I’m sorry,” wasn’t good enough. He then slowly turned back towards the stage. His message was clear without uttering a word: “You’re not worth my time, pal.”

Deeply ashamed, I recognized I was part of the problem. I never again used racist tropes and jokes and became more active in speaking up when confronted with racist behavior. I regret that it took me 30 years to fully acknowledge my callous and problematic behavior, cease it, and begin the work of learning about racist systems and how our actions, and inactions, sustain them.

My problem sprung its roots during those formative years growing up adjacent to Lawrence, Mass. Known as “Immigrant City,” Lawrence was the first planned industrial city in the United States. I was born there in 1960 and lived my first 16 years a mile north in Methuen.

My childhood was a time and place where people would commonly greet each other with jokes, and racially charged ones permeated the atmosphere. A particularly horrifying one that made the rounds was about a new invention to eradicate Jews during World War II. The inventor had gathered a large crowd of people to see his invention in action. The punch line was having to sacrifice a bystander, of a specific ethnic origin, to grease the machine by exterminating them with his creation.

It was during my time in the U.S. Navy from 1978-1982 when my eyes and ears started to become more tuned into the impacts of poking fun at a person’s ethnicity. I had a Jewish roommate for a stretch. I learned a lot from him about his culture, as well as his love for Death Valley where he grew up. We became good friends. During this time we had a mutual friend from Brooklyn, N.Y., who would relentlessly badger and joke about his religion/ethnicity whenever we were together. This was fertile and familiar ground to me. Even still, I grew uncomfortable with this, as did my roommate.

After a few months of dealing with the situation, my friend asked me to talk with our Brooklyn shipmate, a bruiser of a man, all six feet and 230-pounds of him. I did, at length. He was aghast that his bigoted “fun-making” had caused my roommate so much pain. I drove him to our apartment to face my roommate. He was so profusely sorry that my roommate’s angst and hurt melted away, and stayed away, as the Brooklyn Bruiser never again disparaged my roommate.

My most important early life confrontation with the inhumanity of bigotry and racism came half a decade before my Navy stint. It was in the deep woods of New Hampshire inside a cozy cabin listening to an often told and personal favorite World War II story as relayed by my dear Uncle George. It included a near-death experience as an enemy artillery shell hit the chimney of the house Uncle George and his Army squad were sheltering in between days of house-to-house combat in Europe. The story always ended with Uncle George talking about guarding German prisoners of war captured during their brutal combat. Along the way there were the stories of squad buddies killed amid the hell of war.

After this particular telling, I asked my uncle if he hated the German POWs. His response was, “Not at all. They were just like you and me with family at home who loved them. They were thrust into this just as we were fighting a war for their government. Now the Nazi government, I hated them.”

I regret not fully embracing his wisdom as a pre-teen. Doing so would have eliminated a lot of pain and shame, for myself and others. Today, I try to hold on to his words and I am forever grateful he responded the way he did.

Let’s be better humans.

Bill “Guillermo” Mash is a Chico advocate, writer and radio personality, and one-man show behind Imagining Community, a grassroots media and civic engagement endeavor “sharing stories that make our collective imaginations sparkle and engage.”

Be the first to comment