In several ways, the Chico City Council meeting Tuesday night (April 19) went like many under the current configuration. Regular attendees let fly their frustrations—a few boiling over into anger—about homelessness and roads. Other residents came to address a hot-button agenda item involving policing. On notable votes the council split along partisan lines, with lone progressive Alex Brown dissenting from her conservative counterparts.

Yet, Tuesday was different from other meeting nights, almost from the start.

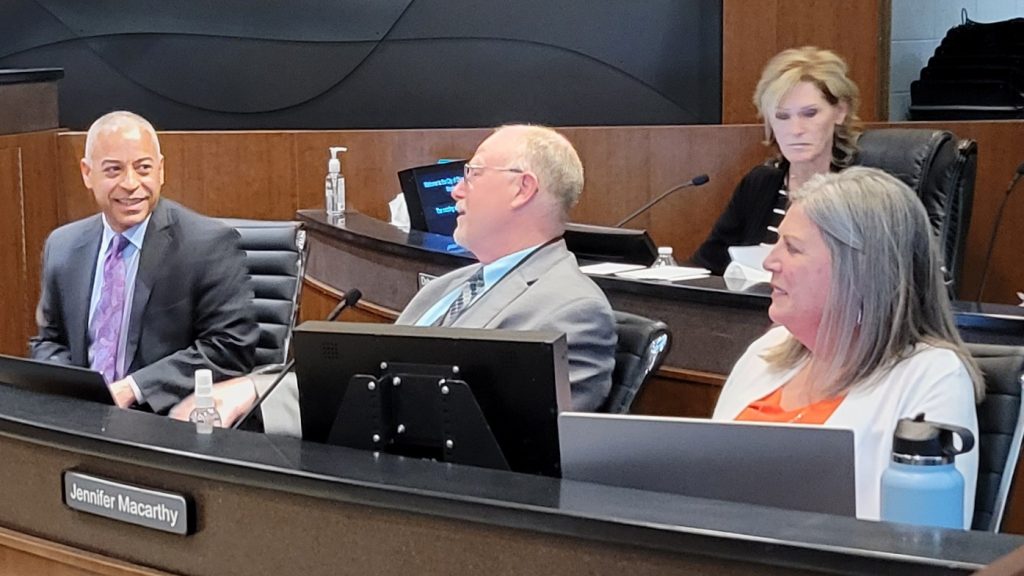

Mayor Andrew Coolidge held a moment of silence for Administrative Services Director Scott Dowell (according to the Facebook page of Sonrise Christian Center, where Dowell was pastor, he succumbed to an illness April 6), and moved to the top of the agenda ratification of Paul Hahn as interim city manager, a hiring the council made at a special meeting April 13. The meeting had two closed sessions—the first wedged into the open session; the second after, as usual—to accommodate performance evaluations of City Attorney Vince Ewing and City Clerk Debbie Presson.

The council affirmed its administrative team, pending the hire of a permanent city manager, by approving Hahn’s contract and giving positive reviews to Ewing and Presson. Councilman Sean Morgan, chair of the performance evaluation committee, gave a particularly glowing endorsement of Presson; he announced that she earned a significant raise (from $145,000 to $165,000) that put her salary on par with other department heads.

Hahn received $207,500—the pay in the contract of previous City Manager Mark Orme—without benefits; he’s a retiree from Butte County, where he was chief administrative officer. Ewing was not subject to compensation adjustment Tuesday, as the city contracts for his services with a firm based in Southern California.

This was technically the third meeting with Ewing and Presson’s evaluations on the agenda but the first with substantive discussion. Thus, the council broke away for 90 minutes, reconvening at 9:25 p.m.

“It’s not fair to evaluate your staff at 11 o’clock at night when everybody just wants to go home,” Morgan told the CN&R before heading into the second closed session, which coincidentally ended around 11.

“I think, honestly, they were both good [reviews]. In the city attorney’s, we’d start talking about stuff that we weren’t there to talk about [i.e., cases] … and in the city clerk’s, we went through all kinds of things—looked back all through COVID, the Zoom meetings she had to set up; we’ve had two council members go away [Kami Denlay and Scott Huber], council member appointments, we lost a city manager [Orme], we lost an interim city manager [Police Chief Matt Madden]. …

“I think the term I used was linchpin. Our city clerk keeps things going.”

Public speakers have consistently shared that sentiment, but they have not been effusive about Ewing. No one called for his replacement Tuesday, but such has occurred previously.

Not speaking to Ewing in particular, Coolidge told the CN&R by phone the next morning: “Whereas the community might have an issue one way or another with somebody, they don’t necessarily see the day-to-day workings that we see, so our perspective is different sometimes than the community’s perspective.”

Brown’s perspective differs, too. She echoed colleagues’ support of Hahn, both with her vote and words. On other matters, she articulated a divide—not only within the council but citywide.

“We really needed a transition in leadership at the administrative level with the city manager,” she told the CN&R by phone. “I’m hoping Mr. Hahn will be the kind of collaborative, transparent and steady leader that we need at this time.

“This council has a propensity to position things as being all fine and sunshine and rainbows and we’re doing great. I think last night, some of the tone that was shared about the transitions that we’re facing and our next steps kind of reeked of that. I struggle a little bit with that, given the theme of lack of transparency with the public and pretty significant changes in our community that have led to some pretty significant consequences.”

Policing, planning

The police policy item represented the final reading of a city ordinance codifying provisions of Assembly Bill 481, which requires a law enforcement agency to get approval from its governing body for armaments classified as military equipment.

The council considered the policy twice before, at meetings March 15 and April 6, when it advanced on 6-1 votes with Brown dissenting. Tuesday was its designated public hearing, and a dozen residents spoke out—nine opposed to the ordinance specifically if not police militarization in general.

One who voiced both concerns, Margaret Swick, told the council: “We need collaborative, community policing. We want you to establish a police culture of de-escalation rather than authorizing military equipment to manage our problems.”

With barely a pause after the comments, Councilman Michael O’Brien (Madden’s predecessor as police chief) moved to approve the policy, which Councilwoman Deepika Tandon seconded and again passed 6-1.

“It is no surprise to me, it makes complete sense, that members of the public would come not just to discuss the policy but to discuss the tenets, the idea, of using military equipment in police work,” Brown said. “My throughline of voting no on this isn’t because I don’t see the necessity of the bill, [the city] being in accordance with state law; it’s because it has taken quite a bit of effort to make it a transparent process as outlined by the bill.”

Madden told the CN&R that he has “no problem with the transparency model” of AB 481 that informs the public, “but unfortunately, the vagueness in the title [i.e., “military equipment”] was designed to provoke some of the anxiety that you saw tonight.

“The Chico Police Department doesn’t plan to add any additional specialized equipment that we don’t already have. We’ll continue to do outreach—we have another public engagement coming in the next few months—so we can continue to educate the public what the bill really means.”

Tandon, a recent graduate of the department’s Citizens Police Academy, and Coolidge distilled the crux to potential need and trust of Chico officers. Coolidge cited the Pioneer Days riot in 1987 as a precedent in the city. Tandon compared equipping police to “an insurance policy—we all buy it on our homes, but that doesn’t mean we file claims all the time.”

She continued: “If we see excessive use or something objectionable, we will review it every year. But at this point in time, I feel we already have a lot of regulations on law enforcement.” With public speakers, she said, “I don’t think it was more about the officers, it was more about the guns that I heard people are more afraid of—the equipment, not the people handling the equipment. That’s what I heard.”

Partisan lines also delineated a development debate in which Morgan pushed to undo a hold on special planning areas (SPAs) from the general plan. The previous council—of which Morgan, Brown and current Vice Mayor Kasey Reynolds were members—voted in 2020 not to consideration of these five expanses along the Chico’s periphery until the city updates its housing element and general plan.

Brown objected to the timing, both on the clock (the discussion began at 9:30, with just three residents remaining) and the calendar. The council is due to review the housing element this spring. In addition, she found the staff report lacking in details that would help citizens unfamiliar with city planning understand the issue.

Nonetheless, the council approved Morgan’s motion, 6-1.

“The housing element will still come,” Tandon told the CN&R. “I don’t think just saying we should talk about special areas means we are going to start development on them tomorrow. We still need to see what we will allow on them. So I don’t think it was a hasty decision.”

Before heading to the second closed session, council members got another presentation about road conditions. The council heard at the Sept. 21 meeting that city streets averaged 49 out of 100, “poor,” on the pavement condition index. Since then, that figure has dropped to 46, and for Chico to improve its PCI to 65, on par with the state average, the city would need to increase its road budget to $15.6 million a year for 10 years—a $13 million annual increase.

Be the first to comment