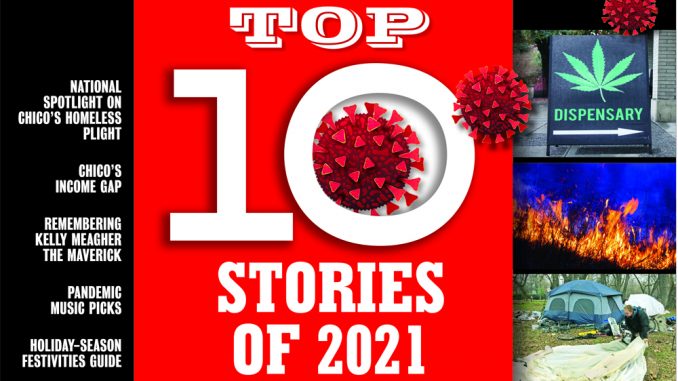

There is no sugar-coating it: 2021 has not been easy. America as a whole may have gone through more turmoil during the previous year, but Butte County had the unrelenting wildfires and extreme drought of our region added to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on public health and the economy, plus the worsening housing crisis, homelessness epidemic and increasingly toxic public discourse in the political arena, often playing out on social media.

But it’s not over: This Year in Review issue is coming out in early December, so even though the CN&R’s top 10 local stories—and the dozen-plus What Were They Thinking? tidbits—in this 2021 look-back don’t feature much good news, there is still time for some positive stories. Some more rain, maybe? PG&E settlement checks for Camp Fire survivors? That would certainly take the edge off the year.

Homelessness

With the exception of a global pandemic, issues surrounding Chico’s homeless population have dominated public discourse and local politics more than any news.

Early in the pandemic, the then-sitting City Council relaxed Chico’s camping laws to comply with guidelines from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to limit the virus’ spread among the unhoused, leading to a boom in visible homeless encampments. The previous council also approved roughly $2 million to fund new shelter and sanctioned-camping options, and the city hired a new Homeless Soultions Coordinator, Suzi Kochems, who initially worked hand-in-hand with service providers trying to get those projects off the ground.

A conservative-majority council took control last November, driven largely by the winning candidates’ promises to clear out these encampments. Those enforcement efforts began Jan. 12, when police and city employees broke up camps in lower Bidwell Park—the first of several “sweeps” of areas where campers congregated. Each of these sweeps was met with large protests, which continued outside of City Council Chambers during meetings.

As this drama played out, the new council backed away from plans to develop sanctioned camping at the Silver Dollar BMX site, and in May, Kochems said the council was not seriously considering new camping, parking or shelter sites. Instead, she said, it argued that shelter space currently in development was sufficient, that the city didn’t have a shelter crisis and that homeless people simply preferred a “nomadic” way of life. The CN&R revealed this questionable conclusion, and related strategies were developed in closed-door meetings between the city and Butte County. Kochems left her job in July.

Meanwhile, as the city prepared to sweep the last remaining large local encampment at the Comanche Creek Greenway, a federal judge approved a temporary restraining order against such enforcement. This was part of Warren v. City of Chico, a lawsuit filed in April by Legal Services of Northern California on behalf of eight unhoused people claiming the city’s existing anti-homeless ordinances and camping enforcement efforts defy the rights of the unhoused.

In June, the city opened the Airport Resting Site, a fenced-in and sparsely outfitted “shelter” site at the end of a runway with 571 chalk-outlined spaces for campers. The site didn’t fly in the judge’s legal opinion, and the city announced its closure in September.

Due to confidentiality requirements, the parties in the lawsuit stayed largely mum about other steps toward solutions, but the city began developing a pallet shelter and camping site at the BMX site with a $1.7 million allocation from the county. The city also engaged in court-ordered settlement talks with the LSNC and its clients while a conservative group fronted by Chico attorney Rob Berry attempted to intervene in the lawsuit, saying the current council has failed to protect the city’s waterways and parks.

COVID-19 persists

As 2020 faded into the rear view, hopes grew that the pandemic would wane as well, particularly with the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines. Nope—the spread of the highly contagious delta variant, loosening of restrictions on commerce and gatherings, reopenings of schools and resistance to face coverings and vaccination all coalesced into a surge greater than in the previous year.

Butte County ended 2020 with 8,261 confirmed cases and 130 deaths since the first local positive test last March. Through mid-November of this year, county Public Health had recorded 13,299 additional cases—4,925 in a late-summer spike (Aug. 2 to Sept. 20)—and 168 more deaths. Hospitals across the nation reached their capacity for intensive care; locally, as patients flooded the emergency room, Enloe Medical Center expanded its ICU to accommodate the surge.

Enloe began releasing daily updates showing the majority of its COVID patients were unvaccinated. County hospitals joined Public Health in promoting initial doses of the vaccine as well as boosters. The rollout of vaccinations began with front-line workers (e.g., health care), seniors and people whose health conditions make them susceptible to illness, then proceeded to other adults, then teens. A vaccine for kids got approved in the fall.

Nonetheless, only half of eligible Butte County residents ages 5 and up were fully vaccinated by mid-November with 5.5 percent partially vaccinated, leaving 44 percent unvaccinated heading into the holiday season.

Perennial wildfire

Unfortunately, 2021 marked a year that included yet another record-breaking local megafire. The Dixie Fire ignited on July 13 in Butte County, then tore through five counties and set the North State ablaze for over 100 days, destroying 1,329 structures—including the town of Greenville—and displacing thousands of people. The fire burned over 960,000 acres before it was extinguished in October, winding up as the second largest fire in state history.

PG&E reported that its equipment could have ignited the blaze, and delivered images to a federal judge of a tree leaning against a power line as well as the remains of its scorched trunk at the fire’s point of origin. The Dixie Fire’s cause remains under investigation by multiple agencies, including the Butte County district attorney’s office.

As it promised for Paradise in the wake of the 2018 Camp Fire, PG&E committed to bury 10,000 miles of power lines underground in “high fire threat districts.” A statewide watchdog and advocacy group, the Sierra Club’s Utility Wildfire Prevention Taskforce, has pushed the utility to implement safety upgrades—specifically, insulated wires that won’t arc or spark when dislodged (as may have happened in the Dixie Fire) and a remote current-interruption system that not only cuts off the electric flow immediately but also identifies the exact location of the problem.

Earlier in the year, the California Public Utilities Commission reprimanded PG&E for not doing enough to maintain its grid in order to prevent forest fires and called into question its tree-trimming methods. Spokesman Paul Moreno told the CN&R that PG&E is ramping up the upgrades, “but it takes time to be able to get the resources and human resources to work toward that goal.”

Recall bids

The second year of COVID brought a statewide recall linked to the pandemic, a local effort that failed to take root and another with an undetermined prognosis.

Fueled by the bad optics of a maskless Gov. Gavin Newsom at a party during lockdown, detractors mounted a gubernatorial recall. They gained enough signatures to force a special election, but in a Democratic-majority state and with a right-wing Republican as the poll-leading alternative, Newsom easily held onto his job—though at a cost to the state of about $300 million.

Around the same time, a group of Chicoans mounted a recall drive to oust four members of the Chico Unified School District board who had voted to maintain remote learning until this fall. That push for signatures fizzled soon after Newsom’s victory.

Most recently, in November, a citizens group called Chico Voters initiated recalls of Mayor Andrew Coolidge and City Councilman Sean Morgan, both conservatives in the first year of four-year terms. Morgan, a former mayor, represents the more conservative District 1 in north Chico; Coolidge represents the campus-area District 5. Recall proponents hope to gain enough signatures (25 percent of registered voters—over 2,400 in District 1 and 1,500 in District 5) in time to qualify for the June primary and avoid the added cost of a special election.

Revolving council chairs

Even in the best of years, Chico’s city politics provide enough drama to keep newsrooms and citizens engaged, but 2021 might have taken the cake. In addition to the city’s ongoing lawsuits, partisan bickering and often dramatic public meetings, two of the seven City Councilmembers quit their posts in the course of a week.

On June 21, Councilman Scott Huber submitted a resignation letter, citing politically motivated harassment. The first-term progressive, who lost his local job during the COVID-19 pandemic, had taken a temporary position in Jackson, Wyo., and purchased plane tickets to return to Chico for the two council meetings during that span.

A social media campaign by the conservative political action committee Citizens for a Safe Chico criticized him for leaving the area to work. In the wake of the PAC’s email blasts and Facebook ads, Huber said both his new employer and his family were harassed online—prompting him to leave public office with around 18 months left to serve.

Six days later (June 27), conservative Kami Denlay resigned after seven months on the job, referencing harassment of her family—stating on social media that “certain members of the community have taken it upon themselves to investigate where my young family lives.”

Though the CN&R never interacted with Denlay’s family (and the councilwoman didn’t reply to interview requests), the paper investigated allegations that she was living outside of Chico while serving on the council. Public records and interviews with neighbors revealed Denlay owned a home in Red Bluff where she and her family resided and which she listed as her mailing address on her voter registration form.

Choosing to fill the vacancies by appointment, rather than special election, the council added two conservatives to the panel: former Chico Police Chief Michael O’Brien and former city Planning Commissioner Dale Bennett. The move pushed the balance even further right, with conservatives going from a 5-2 to a 6-1 voting advantage. However, both seats will be up for election in 2022.

After the fires—struggling to recover

While some survivors of the 2018 Camp Fire and 2020 North Complex Fire made progress toward recovery this year, many more continued to be impeded by myriad factors.

In June, the Federal Emergency Management Agency began charging rent to the Camp Fire survivors living within mobile trailers in its disaster housing developments and subsequently closed all of the developments even though some survivors had nowhere else to go.

Then, in August, Paradise town officials enacted policies geared toward phasing out the use of RVs—one of the primary sources of shelter for many victims of the megablaze—forcing some residents to plead their case to be allowed to stay on their property without facing fines. The Butte County Board of Supervisors voted in November to no longer allow residents to live in RVs without hookups to all utilities (also known as dry camping) after March 2022.

Meanwhile, most fire victims of all income levels await PG&E settlements to help them rebuild, a challenge in itself amid costs inflated by the pandemic.

That’s not to say progress hasn’t been made on the Camp Fire rebuild. Within the town of Paradise, 1,112 homes and 222 multi-family units have been built to date, and another 264 homes have gone up within the burn scar in other areas of the county. Local nonprofits Habitat for Humanity and Community Housing Improvement Program have ramped up their rebuild efforts for low-income survivors.

Drawing on lessons learned from these recent disasters, the county made technology upgrades to its emergency notification system. Most notably, the Butte County Sheriff’s Office entered a partnership with ALERT FM to send evacuation orders via satellite to FM radio stations and to battery-powered receivers in people’s homes. The sheriff’s office also began working with Cal Fire and other departments, including the Office of Emergency Services, to create evacuation zone maps.

Public health politicized

Butte County is on its third public health officer since the start of the pandemic (fourth if counting fill-in stints by Yuba/Sutter counties’ counterpart), and Dr. David Canton, the current official, only has the job on an interim basis until March. That’s not a unique situation: Public Health departments state- and nationwide have grappled with departures as the pandemic places staff—especially personnel in high-profile positions—under extreme pressure.

COVID-19 response became hotly politicized this year, from the Congressional floor to sidewalks. Rep. Doug LaMalfa called for the resignation and prosecution for perjury of Dr. Anthony Fauci, the president’s chief medical adviser. California Assemblyman James Gallagher, another North State Republican, railed and rallied against state public health policies—sparking a picket at Butte County Public Health.

While recently departed Dr. Robert Bernstein didn’t cite pandemic pressures for leaving BCPH, other counties’ public health officers have—noting that they’ve faced death threats and feared for their safety. This exodus, the largest in history with more than 500 in 19 months, includes firings (as happened to Bernstein in Tuolomne County last year, months before coming to Butte).

Vaccinations and face coverings have drawn particular ire from those who believe mandates in these regards violate their liberties. School districts in Chico and Durham also have faced protests over COVID policies, as has Enloe Medical Center.

Commercial cannabis, finally?

Recreational marijuana was legalized in California in 2016, when Propostion 64 passed with 53 percent of the statewide vote. The victory was even more decisive in Chico, with 61 percent approval—yet, five years later, there’s nary a dispensary to be found in town.

Prop. 64 called for local jurisdictions to dictate the rules for commercial cannabis. A commercial cannabis committee including representatives from all sides of marijuana issues—with countless hours of city staff time—came up with a set of rules the City Council voted into effect in October 2020. However, shortly after the new conservative majority took control last December, reelected Councilman Sean Morgan asked, and the council approved, that the permitting process be halted to explore financial structures that more greatly benefit the city.

In May, when the city decided to include Community Benefits Agreements that require applicants to come up with ways they will financially help the city, Vice Mayor Kasey Reynolds stipulated the number of dispensaries be dropped from four to three and that the city hold off on permitting other cannabis businesses (manufacturing, testing, etc.). As the permitting process restarted, the City Council decided to handle appeals of denied permits and spent substantial time in November’s meetings reviewing these staff-level determinations.

More than two-dozen would-be business owners pay rent and overhead costs on spaces where they may not even be able to start businesses. It will likely be more than a year before a dispensary opens in Chico. Meanwhile, local cannabis users continue to spend their money—and pay taxes—on products procured from other areas.

Dangerously dry

California suffered from yet another extreme drought in 2021, facing increasingly warmer temperatures and drier weather due to climate change. Water levels in the state’s major reservoirs dropped far below average this year—Lake Oroville, for example, reached its lowest level ever, at just under 629 feet above sea level and at less than 25 percent capacity, before late-October rains—and rainfall in almost all of the state dropped below half of average.

With most of the state experiencing extreme drought conditions or worse, water rationing and subsequent economic hardship followed for growers in the Central Valley, who received only 5 percent of their expected water allocations from the state. The impacts of the water crisis extended to residential users as well: In Glenn County, dozens of domestic wells went dry between February and June, causing the county to declare a local emergency and plead for state assistance. By May, Gov. Gavin Newsom had declared a drought emergency for 41 counties (including Butte) encompassing more than half of the state’s land, which allowed farmers some relief in the form of expedited water transfers between growers and agencies.

The drought intensified debate on multiple local fronts—notably, the Paradise intertie, a proposal to convey Paradise Irrigation District water to Chico to reduce groundwater pumping by Cal Water; the Tuscan Water District, an agency proposed to procure water for landholders west of Chico; and long-term groundwater sustainability plans due to the state in January.

Chico Scrap Metal

In 2006, the city of Chico ordered Chico Scrap Metal to move from its East 20th Street location, as called for by the city’s adoption of the Chapman/Mulberry Neighborhood Plan. That move has been postponed for 15 years by numerous extensions, legal wrangling and the company’s refusal to budge.

In 2015, conservatives on the City Council led by Andrew Coolidge (currently mayor) paved a way for the business to remain via a city ordinance, but that effort was overturned due to a referendum effort by a group called Move the Junkyard. This, in turn, led to more legal battles—namely an ultimately unsuccessful suit in which CSM joined the city against Move the Junkyard and one of its organizers, Karl Ory, after he was elected to the council.

Citing the costs of ongoing litigation and the chance they may have to move, CSM stopped accepting recyclables in August, leaving the city without a large recycling center.

Now, 15 years after the first amortization order, the end of the battle may be in sight. In October, Judge Tamara Mosbarger ruled against CSM, setting the stage for a relocation. However, CSM owners said via press release that they’re not ready to stop fighting, and it remains unclear if the city is obligated to help the business move. Another court proceeding is scheduled for Dec. 8.

Be the first to comment