As a boy growing up in the Bay Area in the mid-1960s, I had two heroes: my dad and Willie Mays—the Say Hey Kid, the great slugger, center fielder and base stealer for the San Francisco (and New York) Giants. I thought about both a lot this fall as Major League Baseball’s 2021 season wound down.

I loved watching the San Francisco Giants defy early season projections (and betting odds!) by winning a franchise-record 107 games and beating the dastardly Dodgers to win the National League West. Naturally, I’d hoped to be watching them instead of the Braves beat the Astros, but that was fun, too. Except for the Giants, I don’t follow professional baseball all that closely, and I enjoyed watching and getting to know some new (to me) players. I didn’t have much involved emotionally in the outcome, although it was fun to watch former Giants manager Dusty Baker at the helm of the Astros.

(On the other hand, the Astros’ 2017 and 2018 sign-stealing nagged at me, as did Georgia’s new restrictive voting laws, which led Major League Baseball to move the 2021 All-Star Game from Atlanta to Denver, “deeply disappoint[ing]” the Braves, according to a team Twitter post. Georgia governor Brian Kemp responded: “Today, Major League Baseball caved to fear, political opportunism, and liberal lies.”)

I started watching the Giants and Dodgers on our old black-and-white television when I was in second grade. My dad had just moved the family across the Golden Gate Bridge from our apartment in San Francisco to a tract house in San Rafael, though we’d still head back to the City several times a month for his and my mom’s bridge games; and, during baseball season, to watch the Giants—Juan Marichal, Willie McCovey, Orlando Cepeda, and of course Willie Mays—from the Candlestick Park bleachers. I fell in love with the game and wanted to play. In fact, I wanted to be Mays.

Unfortunately, the only “glove” I had at the time was a puffy, cracked, liver-colored boxing glove, the left half of a pair I’d received from Santa a couple of years earlier. I tried to make it work, playing catch with my bare-handed dad on the front lawn after he’d come home from his job as a Caltrans engineer in the City.

In fact, I got to where I could at least sometimes catch the balls he’d throw and the grounders he’d roll my way. (“Two hands!” he’d remind me over and over.) Sometimes I’d grab a bat and stand against the garage door and swat at the tennis balls he tossed. He would have been in his early 30s.

One evening at dinner, he set his fork down beside his plate and looked at me. “We gotta get you a glove,” he said. “Come on.”

We left my mom and little brothers at the table and drove to Taveggia-Brusati Sport and Saddle Shop in downtown San Rafael. There I tried on a couple of dozen gloves before he suggested a gorgeous H-webbed Rawlings, huge for my little hand, and the most expensive one in the store at $29. We didn’t have a lot of money.

When we got home, we went out to the garage, rubbed some neatsfoot oil into the pocket, pushed a baseball into the darker, now-softer cowhide, then folded the glove closed. “Go put it under your mattress,” Dad said. The next morning—after a fitful night’s sleep—I pulled it out, tossed the ball into the pocket about a hundred times, then shoved it back under the mattress and headed off to school. That afternoon, I ditched the boxing glove and played catch with my dad with my new glove until Mom called us in to dinner.

In third grade, the first year I was eligible, I signed up for Little League. “Tryouts” would be held on a Saturday morning in March at my grade school. Managers would meet one evening later in the week to “draft” players. Generally, first-year players, third graders, went into the “minor” leagues, where they’d play a couple of years before being “called up” to the “majors.” Minor league uniforms consisted of caps and jerseys only; major league uniforms were the real deal, including trousers and striped, stirrup-style socks.

Tryouts were scheduled to begin at 9 a.m. Saturday. My dad and I got to the field about 8:15 and played catch as the other kids and dads showed up. Over the course of the next couple of hours, the managers ran us through the drills: ground balls, fly balls, batting. I didn’t feel like I did all that great.

The following Friday evening, the phone rang. It was Mr. Dokken, manager of the Marinwood Giants, calling to say that he’d drafted me—and that I was the only third grader drafted into the majors. He was on his way over with my uniform.

The Giants! I was ecstatic.

When he got there, I went into my bedroom and put it on (though I struggled a bit with the socks), then strode back out to the living room. Mr. Dokken nodded approvingly. “Go into the bathroom and take a look in the mirror,” my dad said.

Oh no! Huge problem: The “G” on my cap and the Giants letters across the front of my jersey were backward! I didn’t understand at first why they laughed when I told them.

My dad accepted Mr. Dokken’s offer that night to be his assistant manager.

While it was pretty cool to be the only third grader drafted into the majors, it might not have been the best “career move.” I soon learned that Mr. Dokken had drafted me to develop me for later—fifth, sixth grade—and that while I got a lot of practice in, I wasn’t getting nearly as much playing time as my friends in the minors were. I rode a lot of pine that year.

But I stuck with it, and each year got more game time, mostly at second base.

Of the 40 or so games I played in my four years as a Marinwood Giant, one stands out, and it wasn’t even a league game. Somehow Mr. Dokken had arranged a game inside San Quentin State Prison, against guards’ and wardens’ sons. One afternoon, the team crammed into the beds of a couple of pick-up trucks, and my dad and Mr. Dokken drove us 10 miles south down Hwy 101 to the prison, where an armed guard opened the gate, and we followed a prison Jeep to the field. I don’t remember whether we won or lost, but I remember guards watching from their towers and prisoners watching from the yard on the hill behind a 12-foot barbed-wire-topped chain-link fence. The rumor that the umps were prisoners was never confirmed, although they were the only ones unarmed.

In junior high, I moved up to Pony League and played two seasons behind the plate. My dad coached both years.

But things were changing. Girls were getting interesting to me, as were the psychedelic light shows and live bands at school dances. My eighth-grade girlfriend gave me Cream’s Wheels of Fire for Christmas. Summer going into ninth grade, I heard a very different version of “The Star-Spangled Banner”—by Hendrix at Woodstock, even more outrageous and controversial than Jose Feliciano’s at Game 5 of the World Series in Detroit the previous year.

I played on the freshman high school basketball team (my dad, having attended the University of Arizona on a full-ride basketball scholarship, rooting me on) but bailed mid-season. In January, I joined a ski club. Instead of running up and down the floors of a sweaty high school gym on Saturday afternoons, I spent them on the slopes at Squaw Valley (now Palisades Tahoe).

In fact, I turned my nose up at school sports. In Marin in the early ’70s, being a jock was not cool. Our teachers even teased the varsity players when they wore their jerseys to school on Fridays.

On top of that, my dad and I weren’t seeing eye to eye as much as we once had. We took opposite sides on the Vietnam War, for example, and our different views were “perfectly clear” to our neighbors when both our cars were parked in the driveway—a Nixon bumper sticker on his Plymouth station wagon, a McGovern sticker on my Mustang convertible.

On the other hand, my friends and I still managed to include baseball in our lives, with pick-up games at local grade schools on Saturday afternoons, often rolling joints (from $10 lids, which we split at least five ways) in the dugout.

The first week of January of 1973—having graduated high school mid-year—I headed for the Colorado Rockies to spend the winter skiing, my Rossignols angling up off the trunk rack of my Mustang. My dad didn’t even wake up to say goodbye the pre-dawn morning I left. A week later, I picked up a heavily bearded, huge-parka-ed hitchhiker outside of Dillon, Colo. The ski resort he worked at was looking for lift operators, he said, and he was looking for a roommate. The next day, I had a job at Arapahoe Basin in Summit County and a roommate.

The best part of the job was the every-Saturday-after-work softball game on skis. We’d set up on the mostly flat ski school area next to the lodge and, using slalom poles for bases, take on the lift operators and ski patrol from the other nearby resorts—Keystone, Breckenridge, Copper Mountain, Vail—each team with eight or nine outfielders, ski-skating madly after fly balls, never catching one. We laughed a lot and put away a lot of Colorado Kool-Aid.

I spent the next two years in South Lake Tahoe, working at Heavenly Ski Resort—winters as a ski-lift operator, summers bussing tables at the restaurant at the top of the tram. One day, checking my “general delivery” mail at the post office in South Shore, I got to talking with the mail clerk, who mentioned that he had a coffee-delivery business that sponsored a men’s softball team and was looking for players. The following Tuesday night, I was playing second base under the lights for Tahoe Coffee Concern.

In May of 1978, after having moved to Chico two years earlier to attend Chico State, I hopped on a plane for Fairbanks, Alaska, and spent the summer helping some high school buddies who’d moved up to work on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline build a house for an oil executive. I lived in a small abandoned trailer in the woods, no electricity, no running water, showering in the men’s locker room in the gym at the University of Alaska every night after work.

And, of course, I found my way onto a softball team, playing shortstop with a scruffy, Libertarian-leaning group of plumbers, carpenters and electricians. The major difference between playing in California and Alaska? No artificial lights for night games. No need that far north. Oh, another difference: a surprising number of guys in the stands openly packing. I made it a point not to argue calls.

The following summer, 1979, I was invited to join the Pests, a Chico Area Recreation and Parks District softball team founded five years earlier by Chico State art and English department faculty and grad students (originally sponsored by George’s Pest Control, hence the name). I played shortstop the first couple of seasons, then moved around over the next 30 years, playing every position except pitcher, ending up—like so many graying, shuffling, Ibuprofin-popping former self-defined hotshots—at catcher, the perfect place to spend my twilight seasons.

The Pests are still going strong, 47 years after their first game, with a new crop of 20- and 30-somethings carrying on the legacy, their families rooting from the stands. Over those years, a number of Chico News and Review writers and editors fielded grounders, chased fly balls and sped (or limped) around the bases in Pests jerseys. Among them: Gary Fowler, Ken Connor, Joe Martin, Bryce Conrad, Joe Kane, Clark Brown, Larry Tripp, Mark Peterson and iconic film reviewer Juan-Carlos Selznick (a founder, who played a Pest-record 42 seasons until retiring in 2016). Former editor Fowler left Chico in 1985 to work in San Francisco with Nibbi Brothers Construction, spending 10 years on three major Candlestick Park renovations. When he returned to Chico in 1996, he went to work for Modern Building (he’s currently vice president), where one of his first jobs was managing the renovation of Chico State’s baseball field and its conversion to Nettleton Stadium.

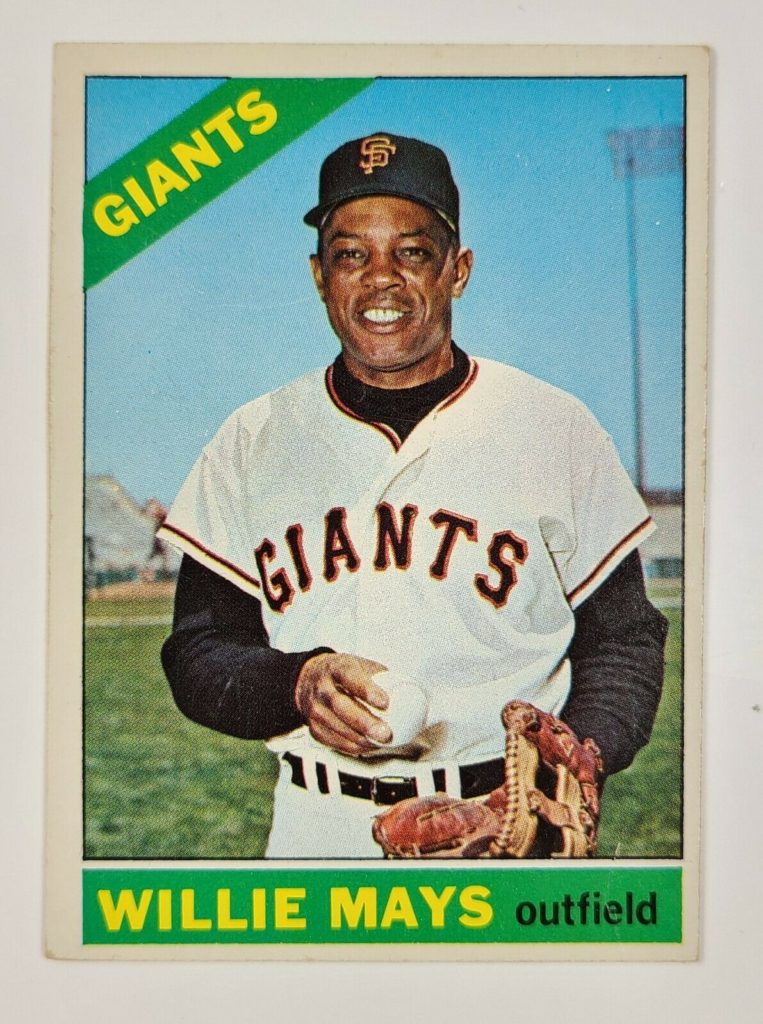

Willie Mays was born in Westfield, Ala., in 1931 and learned the rudiments of baseball from his dad, a railroad porter and semi-pro ballplayer. The two started playing catch when Willie was five. In 1948, Mays signed with the Negro League Birmingham Black Barons. He was still in high school. (While Jackie Robinson had famously broken Major League Baseball’s “color barrier” the year before, Negro League Baseball would continue until 1951.)

Mays played for the New York Giants from 1951 (when he was Rookie of the Year) until 1957, when the team moved to San Francisco, the airline industry having made cross-country team travel possible. “The Catch,” his over-the shoulder grab (and spin-around throw) of Vic Wertz’s 425-foot fly ball in the 1954 World Series against the Cleveland Indians, is still considered one the greatest plays in the history of sports. Mays got a standing ovation in his last at-bat at the Polo Grounds in New York.

When the Giants moved, their hugely popular centerfielder was in for a shock. His offer on a house in an exclusive, all-white part of San Francisco was rejected; the seller/builder feared that if he sold the home to a “Negro” that his business would suffer, and he caved to neighbors’ fears that their property values would be reduced.

Ultimately, Mays got the house, thanks to support from the NAACP, Mayor George Christopher and the Council for Civic Unity of San Francisco. He went on to play for the Giants—and electrify Bay Area fans—until 1972, when he moved back to New York and played one last season and a half for the Mets.

The day after his last game with San Francisco, the Giants officially retired his number, 24. In 1979, he was inducted into the Baseball of Fame, and in 1999, The Sporting News named him second on its list of the 100 greatest baseball players of all time, behind Babe Ruth. He’s sixth on Major League Baseball’s list of all-time home run hitters. (Had Mays not missed most of the 1952 season and all of 1953 after being drafted into the Army, he surely would have ended up closer to the top of the list.)

In 2000, Mays founded The Say Hey Foundation to provide opportunities and safer communities for underprivileged youth and to restore the youth baseball facilities at Rickwood Field in Alabama, the former Negro League home field of the Birmingham Black Barons.

In 2015, President Obama awarded Mays the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

For many years, I taught an introductory American studies course at Chico State. For their end-of-semester projects, the students had to team up and choose something that they thought represented the American experience and present their cases to the class. Nearly every semester, there was a presentation on baseball, the best ones comparing the sport’s complexities and contradictions to the country’s.

The students talked about how baseball offers a “level playing field,” endless opportunity and every spring a chance to start over—for some. They talked about the diversity of the sport, while looking at the ugly racism of its past. They told rags-to-riches stories of poor kids from the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico and Japan becoming millionaires in their early 20s, while still being essentially “owned” by bigger bucks and corporate interests. They talked about cheating (sign-stealing and illegal substances, both ingested and applied to gear) and betting. They talked about modern ballparks’ multi-ethnic food kiosks, where you can get a Korean taco and a local craft beer (for a mere $25 or so). They talked about an entire stadium singing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” gloriously, together as one, then fans fighting in the parking lot.

And they talked about the democratic nature of the sport and that, while there are bona fide stars, the team needs the selfless contributions of all of the players if it is to succeed. As coaches love to say, “There is no ‘i’ in ‘team.’” And as my dad loved to say, “Always hit the cut-off man.”

Watching the playoff games and World Series this fall, I kept thinking about how different baseball is from other sports. While there’s still the occasional bench-clearing brawl and the just-struck-out-batter’s scowl (both mostly theater), you don’t see the trash-talking and anger. Instead, you see players from opposing teams—often not sharing a language—laughing together, one player on the base, his opponent standing on the infield dirt beside him.(In the 1970s, George Carlin reflected on the differences between football and baseball, including, “The object in football is to march downfield and penetrate enemy territory … in baseball, the object is to go home!”)

I’m convinced baseball was one of the biggest influences on how I would grow to see and live in the world. Except for a tiny tucked-away corner, Marin County when I was growing up in the 1960s was about as lily-white as it gets. I think there were two African-American kids in my grade school—one of whom, two years my senior, was my teammate on the Marinwood Giants. But watching Mays, Marichal, McCovey, Cepeda, Roberto Clemente, Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson helped show me what much of the rest of the world looked like and taught me how we should all be treated. And playing in Little League, on skis, in Tahoe, Fairbanks and on the Pests taught me the value of teamwork and respect for not only my teammates but for my opponents.

Today the Giants play at Oracle Park, seven miles north along the west shore of the Bay from Candlestick (razed in 2015). Its address is 24 Willie Mays Plaza. At the main entrance is a 9-foot-tall bronze statue of Mays, having just completed one of his poetry-in-motion swings, his cap tipped back, his eyes following the ball, clearly going, going, gone.

Willie Mays turned 90 on May 6 this year. The oldest living Hall of Famer, he celebrated at Oracle Park, waving with his cap to the standing crowd as he circled the field in the passenger seat of a 1956 Oldsmobile convertible, both the Giants and San Diego Padres teams standing atop their dugouts in salute. The same day, the Giants Community Fund announced the formation of Willie Mays Scholars, a scholarship program to support Black youth in the City. The Giants went on to win 5-4.

My dad retired from CalTrans in 1988 and stayed in San Rafael. I visited when I could, and every few years we’d squeeze in a Giants game—sometimes taking the ferry from Larkspur, past San Quentin, prisoners watching from that same yard on the hill as we sailed by. On one of his and my mom’s visits to Chico, he took in a Pests game.

He continued to vote Republican up until 2012, when he voted for Obama.

The last time I saw him was in March 2015. He had Lewy body dementia and was living in a small single room in a group home in the East Bay. He died a month later at the age of 85.

Great article! Like you, I was a Giant back in the 60’s. I was at the game when Juan Marichal “Clubbed” LA Dodger Johnny Roseboro with his bat!

I thought of that trailer in Fairbanks as mine. It was a great pad! Even greater memories. Thanks Steve.