This feature is part of special wildfire report on the one-year anniversary of the North Complex Fire’s destruction of Berry Creek and Feather Falls. Find links for more articles in this series at the end of this story.

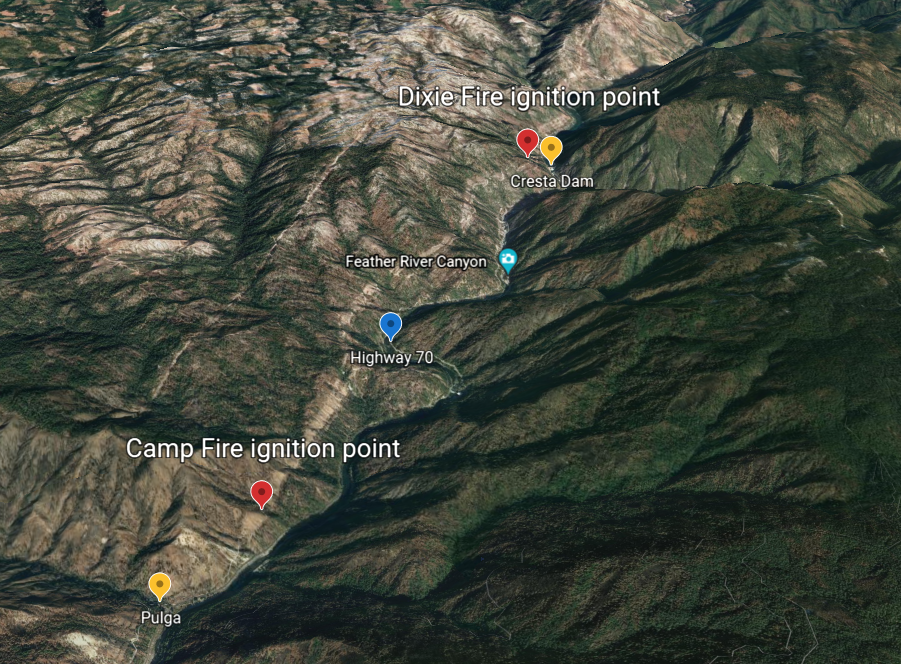

There’s no easy way to get to where the Dixie Fire started. The “point of origin,” as it’s known in fire terminology, sits on a steep hillside off a one-lane dirt road about 8-1/2 miles from the tiny foothill community of Pulga, at the edge of the Camp Fire burn scar. In many spots, the maximum possible speed is less than 5 mph.

Robin McCollum made the trek last Friday (Aug. 27) looking for answers. A retired Butte County tree foreman who chairs the local environmental group Chico Tree Advocates, McCollum has spent the last three years as part of the Sierra Club’s Utility Wildfire Prevention Taskforce, a statewide group tracking fires caused by electric utilities. Top of their watchdog list is Pacific Gas & Electric, which was responsible for the 2018 Camp Fire in Butte County, the deadliest wildfire in California history, and is possibly to blame for the Dixie Fire, which ignited July 13 and is the state’s second-largest ever at over 807,000 acres as of CN&R deadline.

McCollum and his task force colleagues had sifted every detail from PG&E reports and press conferences about the Dixie Fire. They knew the account: a power outage early that morning; a blown fuse, spotted hours later by a Chico-based “troubleman” via binoculars from Cresta Dam, a quarter-mile up the Feather River Canyon; a nine-plus hour journey for that PG&E employee to reach the spot; a Douglas fir, burning at its base, fallen on distribution lines; and a fire spreading down the slope.

Accompanied by the CN&R, McCollum made his way to the source. Much of the relevant hardware—wiring, fuses—and the tree in question had been removed, as expected for a fire under investigation; but McCollum saw enough with the line of power poles, the tree clearance pattern and the forest terrain.

“In that rugged environment, response to a fire is critical,” he said. “Quick response is critical. Anybody is going to have trouble getting there in time.

“PG&E had numerous resources. They had different routes they could take to get there. They had a helicopter they could have observed it with [and] call it. Or they could have just called it [a presumed fire situation] because the circumstances were it was hot, low fuel moisture, a high fire threat area—and if there’s an outage, 90 percent of the time, there’s going to be sparks.

“And, of course, there were.”

Crux of the matter

McCollum’s concerns transcend the Dixie Fire. He started focusing on PG&E after observing questionable tree-cutting practices in the wake of the Camp Fire, both by PG&E and Butte County (see “Uprooting concerns,” Sept. 4, 2019), and what he considered slow progress by the utility in providing safer power lines to Paradise. While attending California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) hearings, he encountered members of the Sierra Club task force. He’s now among 10 core members in a group of 40.

The task force is pushing PG&E to do what utilities to the south—Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric—have been doing with their power distribution networks: update for safety. Specifically, the task force calls for insulated wires that won’t arc or spark when dislodged (as appears to have happened in the Dixie Fire) and for a remote current-interruption system that not only cuts off the electric flow immediately but also identifies the exact location of the problem.

Currently, members explain, the wires PG&E has running through fire-risk areas lack insulation; in describing the situation, McCollum evokes imagery of the insides of a toaster. The utility has 25,000 miles of power lines though areas considered high risk for wildfire.

Much of the current circuit-breaking relies on expulsion fuses: glass-encased metal components that, when blown, become molten projectiles ejected from the power pole. Not only do these fuses pose fire risks should they contact flammable material, those breaker units do not transmit a signal to PG&E to indicate an outage.

“I’m seeing a very dangerous situation that the majority of people aren’t aware of—as I wasn’t,” Dan Courtney, a task force member, told the CN&R by phone. A commercial realtor from La Jolla, Courtney manages family property outside Yosemite, in the vicinity of the 2013 Rim Fire. PG&E lines run by his cabin.

“It’s such a big problem,” he added, noting that the distribution lines at both the Dixie Fire point of origin and his site “were built back in the 1950s with technology and materials that were available back at that time—and they’ve never been upgraded or modernized; they’ve just been fixed on an as-needed basis, when something gets really bad or breaks.”

PG&E has pledged to make its grid safer—publicly and to Judge William Alsup, who’s overseeing the company’s probation stemming from its role in the 2016 San Bruno gas line explosion. Since then, along with the Camp and Dixie fires, PG&E has taken responsibility for last year’s Kincade and Zogg fires and the small Bader Fire in Magalia July 14. The Bader Fire, which burned a quarter acre, started when a tree leaned on a wire and snapped it—similar to the cause of the Zogg Fire. Cal Fire determined the Kincade Fire started when a transmission tower cable broke during high winds and arced. The Camp Fire, which claimed 85 lives, stemmed from a high-voltage line breaking free from faulty C-hook that had been in use for nearly a century.

A week after the start of the Dixie Fire, PG&E committed to bury 10,000 miles of power lines underground in “high fire threat districts,” as it has promised for Paradise. Spokesman Paul Moreno told the CN&R by phone that this is the most recent development in PG&E’s Community Wildfire Safety Program (pge.com/cwsp), a “multifaceted approach” that includes hardening its distribution network as well as public safety power shutoffs (PSPS).

“It’s not a destination but a journey,” he said. “And I know that’s a little bit trite and overused in some cases, but it really best describes how we’re approaching a safer grid…. We’re always looking at new and better ways to operate our power grid for safety against wildfires.”

Trees for the forest

PG&E’s most conspicuous efforts have centered on “enhanced vegetation management”—a broad program of trimming, pruning, cutting and removing trees. Its site lists a goal of completing 1,800 miles by the end of the year, out of 2,400 miles total, to ensure a minimum of 4-foot clearances around power lines.

McCollum, an arborist, has long taken issue with the selection process of trees targeted for removal—PG&E’s notably, though also Butte County’s after the Camp Fire. Courtney told the CN&R that he challenged, successfully, PG&E tree removals on his mountain property in the wake of the Rim Fire.

The task force’s overriding concern is proportion: clearance versus equipment upgrades. At a point two years ago when Southern California Edison had committed to replace 5,000 miles of bare wire with insulated and completed 1,200 miles’ worth, McCollum said, PG&E was “creeping up on” 300 miles.

“We want the focus to stop being on trees as the solution when that’s really only 25 percent of the solution,” Nancy Macy, task force chair, said by phone from her San Lorenzo Valley home in Santa Cruz County.

“We’re trying to get PG&E to focus primarily on upgrading its infrastructure in high wildfire threat areas so there will be fewer fires. They keep having fires because they’re depending on cutting down trees to do the job; it’s not.”

After an audit last spring in which the CPUC found that PG&E was focusing primarily on trimming trees that were not in high-fire-risk areas, regulators reprimanded the utility for not doing enough to maintain its grid in order to prevent forest fires. In a separate report, the CPUC’s Public Advocates Office called into question PG&E’s tree-trimming methods, as well, and also criticized the company for moving slowly on grid improvements and for focusing on lower-risk areas.

Moreno said PG&E is ramping up the upgrades, “but it takes time to be able to get the resources and human resources to work toward that goal…. We have tens of thousands of miles of power lines, so this work cannot be done just in a year.” He said the utility’s rebuild work in Paradise—“like for like” but with insulated wiring and stronger poles—was hindered initially due to limited materials. PG&E decided in May 2019 to fully underground the town’s lines, and Moreno said the company is “on track to complete that within four or five years from now.”

After visiting the Dixie Fire’s point of origin, gazing down the row of vegetation-managed poles, McCollum said he’s certain upgraded infrastructure could have prevented the weeks-long devastation. Had the tree fallen into insulated instead of bare wires, no “stray current” would have traveled from wire to wire or by wire to the ground.

“There would have been no short circuit; no problem,” he said. Current-interruption technology would have detected the line break and immediately cut the power flow remotely, thereby eliminating another opportunity for sparking—not to mention the potential of an expulsion fuse blowing (which in this instance has not been found to be the case).

“Looking at 100 million trees and trying to pick the three or four out of there that are going to cause a problem is not the way to go,” McCollum said. “They need a fire-proof system, consisting of insulated wires [and] circuit protection—and a ready response when something happens.”

Jason Cassidy contributed to this report.

Further reading:

“Wildfire country”

“Our wildfire breaking point”

“Accountability”

Be the first to comment