Race is a mirage but one that humanity has organized itself around in very real ways. Imagining away the existence of races in a racist world is as conserving and harmful as imagining away classes in a capitalistic world—it allows the ruling races and classes to keep on ruling. … If we cannot identify racial inequity, then we will not be able to identify racist policies. If we cannot identify racist policies, then we cannot challenge racist policies. If we cannot challenge racist policies, then racist power’s final solution will be achieved: a world of inequity none of us can see, let alone resist.—Ibram X. Kendi, from How to be an Antiracist

When Mechoopda Tribal Council Chairman Dennis Ramirez concurred with Chico State and Butte County on the 2020-2021 Book in Common, then gave a short testimonial, he endorsed the overarching message contained in the title, How to be an Antiracist.

He didn’t reflect on deeper subtexts to the memorandum of understanding he signed—with the university, which sits on land his ancestors inhabited, or with the county, which contested the legitimacy of his people in a series of court cases spanning a decade.

As covered extensively in the Chico News & Review, previous iterations of the Board of Supervisors pursued legal challenges to stop the Mechoopda from developing property along Highway 149. The county’s case questioned whether they constituted a tribe—an argument that, ultimately, did not persuade a federal judge (see “Tribe on top,” July 21, 2016) or hold up on appeal. A new set of supervisors ceased litigation (see “Change of heart,” August 16, 2018), and the Mechoopda are now working on an agreement with the county to build their casino.

Five years ago, thinking back over the legal fight that went back to 2008, Ramirez expressed pain both personal and tribal.

“I think of my mother, my grandmother—my goodness, how can you not say that [the Mechoopda are a Native tribe]?” Ramirez told the CN&R then. “It just blows my mind how people think. Yeah, I could understand it a hundred years ago, but not today.”

Some wounds never fully heal.

Speaking with the CN&R last Wednesday (March 31), again at the tribal office on Mission Ranch Boulevard, Ramirez said the divisiveness “softened after the political part” of the dispute ended, “but as personal thinking, yeah, it still hurts. It will always hurt. Those comments are not going to go away.

“But as a political person for the tribe, I have to make things happen, economically. With that thought, I have to keep that [emotion] to the side and not let it get personal on this economic development portion of it.”

Ramirez’s perspective meshes with key concepts in Ibram X. Kendi’s book. How to be an Antiracist does not focus simply on the individual, though it is written as a memoir; it defines racism more broadly, as a function of policies and systems. Kendi, through his (self-)examination, calls for a reckoning: with personal prejudices, with society, with inequality. He also calls for change.

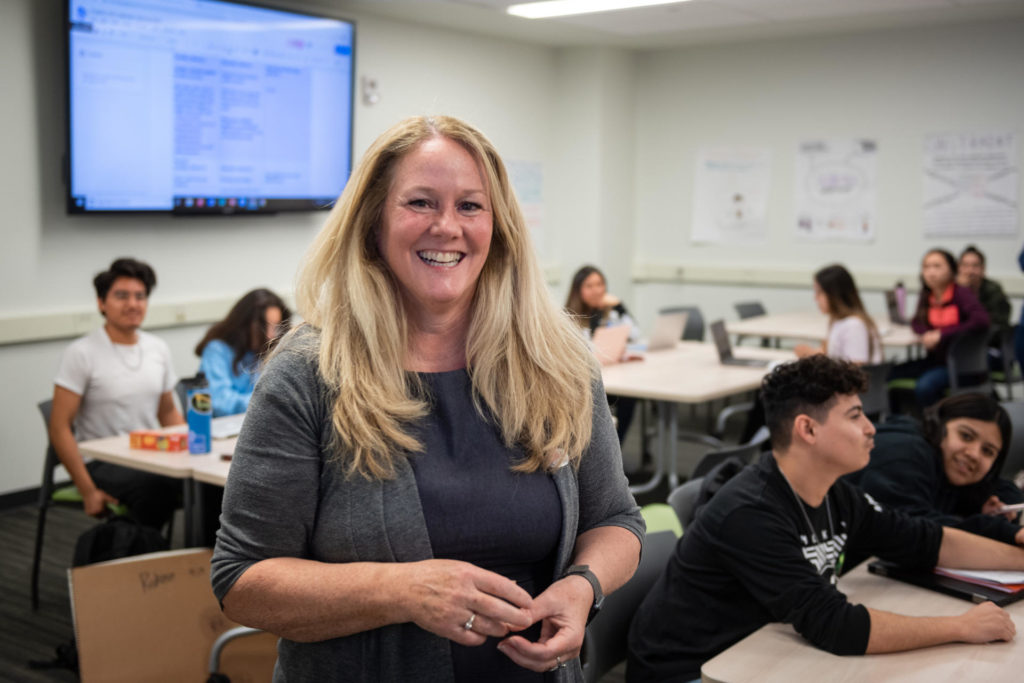

This message resonates with Ramirez, along with those involved with selecting the Book in Common as a centerpiece for education across county schools for the 2020-21 school year. Kendi will participate in an online discussion April 21 hosted by Chico State English professor Kim Jaxon and AS President Bre Holbert (see info at bottom). The conversation takes place against a backdrop of racial unrest in the country—on the heels of a mass shooting of Asian-American women in Atlanta and the murder trial of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for the asphyxiation of George Floyd, whose killing sparked a wave of protests, including large ones in Chico last June.

“Those who are going to read it are going to understand it and those who won’t read it are not going to understand it—but that’s the reason for the book, to be aware of what’s still happening in this beautiful country we still have,” Ramirez said. “From major cities to a small community, you’ll always get that hate. It’s a lack of understanding or a lack of communication.”

Ongoing work

Jaxon’s roots with Kendi’s writing trace beyond How to be an Antiracist, published in 2019. She discovered his work via his 2016 National Book Award winner Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. Jaxon drew further insights from Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019.

Yet, when the Book in Common committee asked her to co-moderate Kendi’s talk, she had strong reservations.

“My first thought, of course, was, ‘You know I’m white?’—and not wanting to center whiteness in this conversation,” Jaxon told the CN&R by phone. “Ultimately, the decision for me became, ‘Yes, this also isn’t just the work for people of color. This is everybody’s work.’ Then it felt more appropriate.

“Of course: This is a conversation we all should be having, not just, ‘Hey, people who aren’t white are having this conversation.’”

She sees the book as a catalyst for that conversation.

Kendi weaves seminal history of Black Americans into his treatise, starting with a high school speech he gave in a Martin Luther King Jr. oratory contest. That day 21 years ago, before an audience of 1,000 in a Virginia chapel, Kendi delivered lines that, upon re-evaluation, he’s come to regret. He writes about the different lens through which he views the past—King’s, his, others’—and the world.

“Americans have long been trained to see the deficiencies of people rather than policy,” he writes in How to be an Antiracist. “It’s a pretty easy mistake to make: People are in our faces. Policies are distant. We are particularly poor at seeing the policies lurking behind the struggles of people.”

As such, Kendi redefines terms in his book: “The opposite of racist isn’t ‘not racist.’ It is ‘anti-racist.’ What’s the difference? … One either believes problems are rooted in groups of people, as a racist, or locates the roots of problems in power and policies, as an anti-racist. One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an anti-racist. There is no in-between safe space of ‘not racist.’”

His call to action connected with Jaxon. She’d already made the commitment to start the reading list for each of her courses with an author of color, but now she’s determined to initiate more widespread institutional changes at the university, where she feels she has the ability to make the biggest impact.

“I really appreciated that this was presented as an ongoing story, that this work was never done—that’s what struck me first,” Jaxon said. “I think I needed in some way permission to not know everything all the time, to know that the work of being an anti-racist is constant and in progress, and that you can wobble on a given day or a moment.

“I think his narrative woven in with policy really helps you put yourself in that narrative and where you are in your own journey.”

A resident of Capay, Jaxon raised her adult children in the 30-mile radius of Chico where her family has lived for seven generations. She noted a proverbial rite of passage for young people coming to terms with attitudes “pervasive” in the rural North State.

“It is a hard lesson … when you recognize the [racial] issues in the community that you also love,” she said. “Especially being white here; it would be so easy to ignore.”

Jaxon hadn’t spoken to Kendi as of last week, and the CN&R wasn’t able to secure an interview with him, but the author has expressed familiarity with at least one local issue of race: He recently retweeted, with commentary, an article last month in the Guardian about unresolved aftermath of Chico police fatally shooting Desmond Phillips, a Black man suffering a mental health crisis, in 2017.

Bigger than oneself

Holbert came to Chico from Lodi, where she recalls her ethnicity raising few, if any, eyebrows. She has African and Latin heritage; with her uncle and mother well-established in the Central Valley town, Holbert recalls no overt discrimination.

That said, she might not have recognized it. Chico State has expanded her awareness of racial issues—and, unfortunately, Chico has demonstrated racism. Besides the occasional look askance, Holbert relayed her experience in a store self-checkout lane one night when an employee asked if she intended to pay for all her items, then hovered. She left feeling “a bad energy” and that she was profiled.

“Growing up as an Afra-Latina, I didn’t feel like I fit into really any box,” Holbert, a senior, said by phone. “I didn’t fit with brown students, I didn’t fit with white students, I was just kind of like this mixed child going through my life and my days, not having a solid group of people I could say, ‘Oh, I relate to them culturally and ethnicity-wise.’

“I mean, I relate to people in my community. But it’s different coming to Chico, because there are people who are like me. Even though this is a more conservative area, the school itself has a wealth of different cultures and perspectives that I identify with.”

The closer she is to campus, the more comfortable she feels. That physical proximity coincides with shared ideas—operating within the same spaces of inclusion, for which she advocates not only within Associated Students but also within the College of Agriculture and statewide Cal State Student Association.

“A lot of times, folks who don’t come from a diverse or ethnic background or a predominantly marginalized group oftentimes will feel this jump to feel guilty about something that is way bigger than them,” she said. “We’re so small in the fabric of this issue, all issues related to race and ethnicity, [that] we all have a part in it and a part to change it.”

Ramirez agrees. During the Black Lives Matter protests last summer, a man came up and screamed at him, “You need to go back where you’re from!” Ramirez replied, “You know, brother, this is where I’m from. I’m Native American.” The man said nothing more and walked away.

“I don’t know if he was looking to instigate trouble,” Ramirez reflected, “but before you open your mouth, know who you’re talking to by simple dialogue.”

Communication—to bridge rifts that cleave our country—is something he hopes will flow from How to be an Antiracist.

“It depends on how many hands that book gets into,” Ramirez said. “Right now, with that trial [of Chauvin], and others, it’s [looking like racism is] going to keep going on.

“Growing up as a brown man, we were never taught to be racist to anybody,” he added. “But then again, a lot of people are embedded by that from generation to generation.”

Chico State will host a virtual event with the author of How to be an Antiracist, Ibram X. Kendi, April 21, at 5:30 p.m. Visit www.csuchico.edu/bic to register, submit a question and learn more about the 2020-21 Book in Common.

Be the first to comment