I’ll never forget the morning after the Camp Fire—Nov. 9, 2018. That’s the day I drove up the Skyway and into the burning hellscape of what I once recognized as the town of Paradise. One of my last impressions of Chico that day was stopping at a checkpoint at the bottom of the Skyway, beyond which only public safety personnel, utility workers and members of the media were allowed.

I was riding shotgun in my colleague’s vehicle, and we readied our press credentials as we approached a barricade and an attendant highway patrolman. After checking our badges, he had only one question for us.

“Know where to go to stay safe?”

It was one of those moments where you quickly have to gauge a response. Mine was honesty. “Nope,” I said.

I mean, how could we? The mega blaze was still raging uncontrollably. At that moment, we knew driving up there was inherently dangerous, but risk-taking is part of the job.

“Well, be careful,” the CHP officer said before waving us through. He obviously had better intel about just how bad things were up on the Ridge. To his credit—knowing we had the right to document the scene—he didn’t attempt to further dissuade us.

It wasn’t my first time driving into an active fire, albeit nothing could have prepared me for bearing witness to the detritus of the deadliest and most destructive fire in state history. I still vividly recall the scene—the stench of toxic smoke and the sound of exploding propane tanks ricocheting around us.

It’s through that lens that I’ve been chewing on a press release from the city of Chico that basically said it did nothing wrong when it barred reporters from getting an up-close look at a recent effort to roust homeless folks—ostensibly due to safety concerns. You know, from heavy equipment, which is laughable considering how many times I’ve walked or ridden my bicycle next to city construction.

Earlier this month, one of the Chico Enterprise-Record’s writers and CN&R reporter Ken Smith, along with a few other journalists, were turned back at a bridge leading to a city-owned property in the Chapman neighborhood where an encampment had sprung up in the wake of a prior eviction at the greenway called The Triangle.

As the city has done on previous occasions when it runs afoul of the law—like the several times in memory it has violated the Brown Act—denial is a key feature. The city’s press release reads, in part: “This perimeter was properly set up to ensure all safety precautions were adhered to and access by the media and protestors (sic) was safely allowed adjacent to the active site.”

Cue the longest eye roll in the history of eye rolls. To the contrary of the city’s hamfisted attempt at public relations—aka damage control—media access was, in fact, denied.

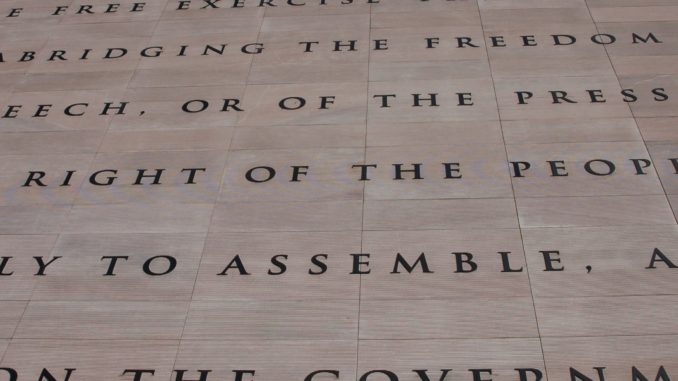

In response, the CN&R signed onto a letter penned by Chico E-R Editor Mike Wolcott chiding the city for, as he put it, the “inexcusable violation of our First Amendment right to report the news.”

With all due respect to protesters, journalists are afforded special privileges. They have a constitutional right to document—without interference and without themselves interfering in—public affairs. The city, including the Chico Police Department, ought to know this.

I’m at home these days, tending to my school-age son, but I know what it’s like to be a reporter in the thick of intense, dynamic situations. Aside from covering wildfires, another incident that stands out was in my early years as a reporter, when I stood my ground as police in full riot gear came marching up Main Street in response to an Iraq War protest that shut down traffic. I was the lone staffer for my newspaper, so I got a crash course in one-woman reporting that day.

“I’m a reporter,” I shouted more than a few times while walking backward to take photos, and hunching over to scribble notes during interviews with the people who’d planted themselves in the middle of the street. The veteran police officers were professional and understood my place on the scene, but there were a few overzealous rookies who needed reminders.

It’s hard to believe that, nearly two decades later and given the focus on media rights over the past four years, the city could be this ill-informed about the First Amendment. Moreover, considering we’re talking about a local stable of journalists that has dealt with multiple disasters in the past three years, I don’t for one second buy the narrative that the city was concerned about anyone’s safety.

What we’re really talking about here is willful interference. Indeed, I believe the real reason the city blocked off the area leading to the homeless encampment was to mitigate damage to its reputation. We’ve all seen the photos of previous homeless roustings. No matter what people think about the squalor of these unsanctioned campgrounds, one cannot deny the suffering wrought by evictions. More to the point, such documentation is part of the record, and may become evidence for pending litigation for civil rights violations.

First Amendment violations aside, if city leaders believe these sweeps are legal and ethical, they should have no problem with journalists freely documenting them. Spoiler alert: They don’t.

Be the first to comment