Whatever new challenges 2021 has in store for Butte County, there is still a lot of work to do to recover from the wreckage of the previous year. Public health, business, education, housing and the environment have all suffered during a year filled with wildfires, civil unrest and a worldwide pandemic.

It’s going to take commitment and many people willing to work together to rebuild our community, and the five subjects the CN&R has chosen to spotlight in this annual Whom to Watch issue are among the leaders tasked with getting us back on our feet.

Working for a better future

Caitlin Dalby

Caitlin Dalby just started two new jobs, and she is approaching both with the focus of making a difference in her community—in 2021 and beyond. In addition to being a newly elected Chico Unified School District board member, she will spearhead the nonprofit Butte Environmental Council as its new general manager.

That’s not to say making a difference wasn’t a focus before—Dalby has been a secondary school science teacher for the past 12 years. She told the CN&R that she’s motivated by her former students, to whom she had to say goodbye in order to assume her post as a district trustee. And, of course, she’s also motivated by her infant daughter, Isla.

“I want them to have a brighter future. It’s a lead-by-example thing: ‘Follow your passions and be the change.’ It’s been what I’ve been telling my students forever,” she said. “And I’m really excited to live that.”

When it comes to her position at BEC, Dalby said she’ll work with her team to continue the organization’s 45-year legacy of environmental stewardship, education and advocacy.

Dalby, who has a master’s degree in land resources and environmental science, takes a holistic view of environmental health. She sees BEC having an important role in many socioeconomic issues, including homelessness and the housing crisis. In addition, she’s planning on exploring projects related to groundwater and surface water health, sustainable land regeneration, urban forest management and wildfire recovery.

In both positions, at BEC and with CUSD, Dalby said transparency is key for her and she’ll always take the approach of asking analytical questions and drawing conclusions based on evidence and data.

As a CUSD board member, she said her No. 1 priority is the health and safety of students, staff and teachers on campuses.

The district needs to err on the side of caution until coronavirus infection and transmission data paints a complete picture of the impacts and risks for students, teachers and staff, Dalby added. She’s a proponent of focusing on how to mitigate spread and continue in-person instruction for those who really need it—such as students with accessibility issues or those suffering from severe mental health challenges.

“Distance learning is not ideal, but it’s not as disruptive as what’s happening right now at the secondary level” with absences among students, teachers and staff due to COVID-19 exposure quarantines, she said. The district needs to “be creative and find out how to make campuses safer and still provide meaningful education to students.”

Dalby also is focused on students’ emotional well-being. She said she’s in support of more primary school counselors—at least one at each elementary site.

“We need to model advocating for ourselves and we need to empower [students] to reach out to a trusted person,” she said. “We really need to work on this personal connection with our students because we’re just seeing that need so much right now, especially over the last few years. With [the] COVID[-19 pandemic], it’s even more prominent.”

—Ashiah Scharaga, ashiahs@newsreview.com

New top doc

Dr. Robert Bernstein

Public Health Officer has not been the most popular job title in California over the past year. Across the state, doctors setting coronavirus measures have left their posts under pressure by policymakers and the public—or due to pressure from the work itself.

Butte County, with the Oroville Dam and Camp Fire crises preceding the current pandemic, lost its public health officer in June. But available and willing to take the job was Dr. Robert Bernstein, who’d served that capacity in Tuolomne County until February, when that county’s supervisors let him go without public explanation. Butte County’s Board of Supervisors approved his hiring in August to succeed Dr. Andy Miller, who remains a practitioner in Chico and in contact with Bernstein.

Known as Dr. B around the Public Health Department, he relocated with his 15-year-old triplets and four cats.

“I’m happy here,” he said—knowing well, from Miller and others, all that Butte County has gone through and continues to endure.

But this is not Bernstein’s first exposure to emergency. He’s worked for the World Health Organization, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Doctors Without Borders and USAID, battling diseases such as Ebola, MERS and SARS. He’s also provided medical relief to tsunami victims in Asia.

“I’ve had my share of experiences working at the international, national and local levels during outbreaks of communicable diseases and other kinds of emergencies,” he explained in a training room at Public Health’s administrative office in Oroville. “There’s a photograph of me being in a small room, about a quarter of the size of this one, briefing President Carter during the Mount St. Helens eruptions [in 1980].

“I’m not exactly uninitiated in terms of emergencies and disasters—but this is the first pandemic that most of us have experienced unless we’re 100 years old in the U.S., so there are a lot of things that are different and challenging about this pandemic.”

Bernstein advocates for preventative measures such as social distancing, hand-washing and wearing face coverings in public. Controversy over the latter, in particular, troubles him.

“There’s so much confusion, I think, over individual rights versus public needs that have led [some] people to take positions and behave in ways that endanger members of their own family and the community,” he said.

In December alone, Butte County experienced more than 40 percent of its 7,390 COVID-19 cases from 2020, and the pace has continued into the new year, with 1,135 more cases through Jan. 10. Coronavirus vaccines will roll out countywide after health-care workers get inoculated—but, once again, Bernstein sees resistance as a problem. Epidemiologists estimate at least 70 percent of the population must vaccinate to effectively stop the spread via herd immunity.

“We really need their agreement to understand the importance of accepting these vaccines in order to protect themselves, their family members and the community at large,” Bernstein said. “At the same time, we need to overcome the anti-vax movement that’s keeping people from vaccinating their children and taking their own vaccines—the dozen or so vaccines that have been shown over the years to be safe and effective.”

Improving health literacy in the county is one of Bernstein’s priorities. He’s also eager to continue efforts championed by Miller to reduce opioid addiction. He has other epidemics in his sights—i.e., adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and tuberculosis—plus expanding access to care.

All this amid budgets cuts and the added demands of a pandemic.

“Our ability to provide essential public health services is constrained,” Bernstein said, “and we’ve had to prioritize our [coronavirus] case investigation and contact tracing…. That’s a problem.”

However, “2021 is going to be brighter than 2020,” he added. “I’m always optimistic; that’s a requirement of a public health officer, to be optimistic.”

—Evan Tuchinsky, evant@newsreview.com

Council comeback

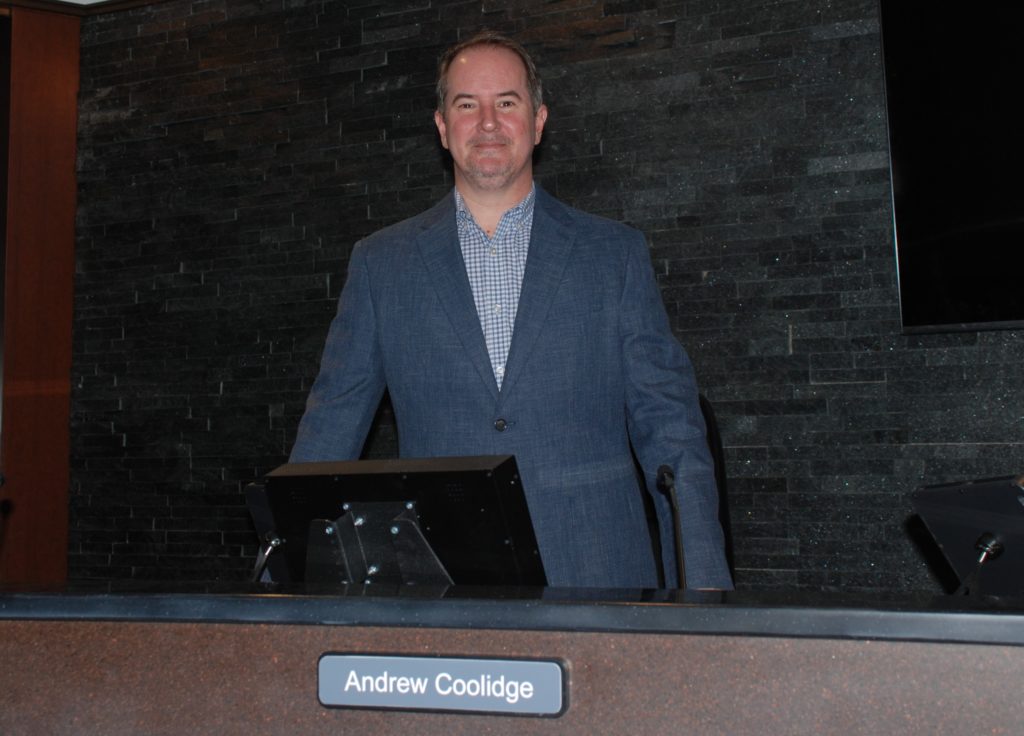

Andrew Coolidge

After falling short of reelection to a second term on the Chico City Council in 2018, Andrew Coolidge felt no rush to return to civic duty.

“Someone would ask me, and I would say, ‘Maybe some day,’” he told the CN&R. “It was something where maybe later in life, maybe in my 50s or 60s, I’d think about trying to run a race to come back to council.”

Then 2020 struck. Coolidge, 48, works in public relations, with the bulk of his business centered on bridal shows and home-and-garden shows; coronavirus decimated the events sector. Meanwhile, Chico moved from citywide elections to districts, and he resides in one—District 5—that was set to be contested.

The nexus of opportunity, plus encouragement of supporters, prompted Coolidge to declare his candidacy over the summer, and he went on to beat Lauren Kohler and incumbent Randall Stone, both progressives. Fellow Conservatives, including incumbent Sean Morgan, also won the other three seats to join Kasey Reynolds in a 5-2 majority that flipped the council’s power balance.

His colleagues punctuated his comeback by electing Coolidge mayor, with Reynolds vice mayor.

“This is definitely not an easy position,” he said, seated in City Council Chambers recently. “I welcome the challenge, but at the same time I realize I’m not going to make everyone happy all the time.

“I’m also going to do it in my style: calm, pragmatic, moving forward at a good pace but welcoming public comment. I’ve never been one to be aching for the center of attention or limelight—that’s not my personality, that’s not who I am.”

His council leadership now belies his position during his first term, when he periodically found himself on his own outside the conservative bloc (then-Mayor Morgan, Vice Mayor Reanette Fillmer and former Mayor Mark Sorensen).

This time, he came into office aligned with councilmembers supported by the political action committee Citizens for a Safe Chico as well as the similarly oriented citizen groups Chico First and One Chico. The PAC spent around $220,000 on the election.

Coolidge acknowledged positions he shares with Morgan and the two new councilwomen, Kami Denlay and Deepika Tandon, on issues such as public safety, homelessness and banning syringe service programs. He also pointed to priorities of his that are not promoted by the others—road improvements; tree-planting in Bidwell Park; solar energy; retrofitting more lighting to LED; irrigation and wastewater efficiency.

“PACs speak with a loud megaphone,” Coolidge said. “I campaign person to person.

“I have a unique way of looking at city government: It’s a little Libertarian, a little conservative and a little socially moderate. Those three things mixed in make me different. I can’t necessarily be put into one box.”

Coolidge credited the previous council for its budgetary response to the pandemic though feels the city can thaw its hiring freeze, as the new council recently approved for the Chico Police Department.

“My goal, really, is to move the city through things business-wise,” he said. “It doesn’t have to be controversial. People get their say, the council moves forward in one direction or another.

“City government only moves so quickly, so I don’t think necessarily we’re going to have rapid change,” Coolidge added. “I think we’re going to make progress—or at least what I view as progress—in a very methodical, steady pace.”

—Evan Tuchinsky

Center of the storm

Suzi Kochems

As large encampments settled into Chico’s parks and along its waterways since the outbreak of COVID-19, public debate on homelessness reached a fever pitch. The scope of the problem is daunting enough; add the contentious debate surrounding it, and Suzi Kochems would seem to have one of the toughest jobs in town.

Kochems was hired as the city’s homeless solutions coordinator in August, a position created in March. She followed Joy Amaro, who left to return to her position as executive director of True North Housing Alliance.

Kochems has been involved in low-income and homeless programming for more than 25 years. That includes a decade-long stint in the Glenn County Health and Human Services Agency’s housing department; serving as coordinator of the Homeless Countinuum of Care for 12 Northern California counties; and other jobs—such as working in grant writing and contract procurement—with Butte and Trinity counties.

“I wrote my very first grant proposal for the Jesus Center many, many moons ago,” Kochems said in a recent interview. She has also worked on the service provision side, for a time running the Westside Domestic Violence Shelter in Orland.

“All of that experience lends me the expertise to succeed at this job, given amenable circumstances,” Kochems said.

However, given the abundance of problems connected to homelessness, “amenable circumstances” are scarce. Kochems may have helped facilitate a big boon to the local fight against homelessness—convincing the Chico City Council in October to allocate more than $2 million toward a number of incentives collectively called the Homeless Opportunities Plan—but little movement has been made on any of the approved schemes. Locations for shelters or designated camping have been hard to come by or barred by restrictions; some options have expired due to slow-moving bureaucracy; there are limited amounts of capable service providers; and myriad other issues have hindered progress.

“Housing the homeless is tough enough on any given day, and then you add COVID in there and it just amplifies the difficulties,” Kochems said.

This lack of apparent movement has driven public criticism and anger, elements that have long complicated everything related to homelessness.

“Every day I’m working with service providers, finding funding, coordinating efforts [between different organizations], meeting with politicians and city staff, and tromping through empty buildings looking for sprinklers,” she said. “It’s a very broad scope of work, and there are plenty of people who haven’t walked two steps in these shoes who are quick to criticize anything and everything.”

Kochems said that, contrary to some opinions about the town being a magnet for homeless people, Chico’s situation is on par with that of other similarly sized cities. She also believes it’s a growing problem that was ignored far too long, one that may worsen in the near future as the economic impacts of the coronavirus continue to wreak havoc on the working poor.

“We as a society and country don’t put enough emphasis on prevention, so when it comes to homelessness, we’re constantly chasing our tails,” she said. “It’s reactionary management. … Now we have to fix the problems we have before we can get ahead of anything.”

—Ken Smith, kens@newsreview.com

Middle man

Tod Kimmelshue

When Tod Kimmelshue was sworn in as a Butte County supervisor on Jan. 4, he filled a spot that could end up being most contentious: that of a tiebreaker.

It’s no secret that the Board of Supervisors—made up of liberals Debra Lucero and Tami Ritter from Chico and conservatives Bill Connelly of Oroville and Doug Teeter of Paradise—has been harshly divided along partisan lines.

Kimmelshue was elected to serve District 4, encompassing southwestern Butte County. The seat was previously held by longtime politician and former Board Chairman Steve Lambert, also a conservative.

Though Kimmelshue, a fifth-generation farmer and retired agricultural finance and banking adviser from Durham, is also conservative, he’s “not a big labels guy”; he says he sees his role on the board as one of “trying to bridge th[e] gap.”

“I can see myself working with all of [my colleagues]. And I’ve told all of them, ‘We’re not going to agree on everything, but I will always treat you with respect.’”

Kimmelshue’s priorities include supporting Camp Fire recovery; public safety and law enforcement; the agricultural industry; the protection and preservation of local water; and the building of a skilled local workforce.

His election win in the 2020 primary was announced just before the initial lock-down order for California in March, so he’s since added the county’s response to the coronavirus pandemic to that list of priorities. He told the CN&R that he is concerned about the vitality of small businesses, particularly those that have been heavily impacted, such as barbershops, salons and restaurants. Kimmelshue is in favor of their opening with “very stringent precautions” and said he’d support pushing back the state’s business closure mandates.

In addition, Kimmelshue has been a vocal opponent of syringe service programs and has publicly praised the Chico City Council’s move to ban them.

“Government’s main job, as far as I’m concerned, is to keep our people, to keep the citizens, safe,” he told the CN&R. “The way the needle program has been going, it is a safety issue for me.”

As an alternative, he said he is supportive of private organizations, particularly the Jesus Center, that can serve as a “guiding place” for those who are struggling with addiction and homelessness.

Other issues important to Kimmelshue are connected to his background, such as “a sustainable and ample water supply” for agriculture, residents and the environment.

Regarding fire safety, Kimmelshue said that the county needs to better manage unincorporated lands in the foothills to be prepared for catastrophic wildfire and that he’ll be looking into proposing some ordinances related to defensible space.

“I think we need to do a little bit better job of being prepared for these type of fires, whether it’s thinning the forest, whether it’s defensible spaces, [whether it’s] tree removal in certain situations,” he said. “I think that’s just very, very important. We still have a lot of area that could burn.”

Ahead of his swearing in date, Kimmelshue told the CN&R that he was prepared to make tough calls for the good of the county, even if it means he’ll take some heat in the event he casts a swing vote, siding with the liberal supervisors instead of his conservative colleagues.

“I want this county to succeed, I want this county to be prosperous, and I want it to be a great place for people to raise a family,” he said. “I want to just do what’s best for the county, and if I’m a swing vote, I’m a swing vote.”

—Ashiah Scharaga

Be the first to comment