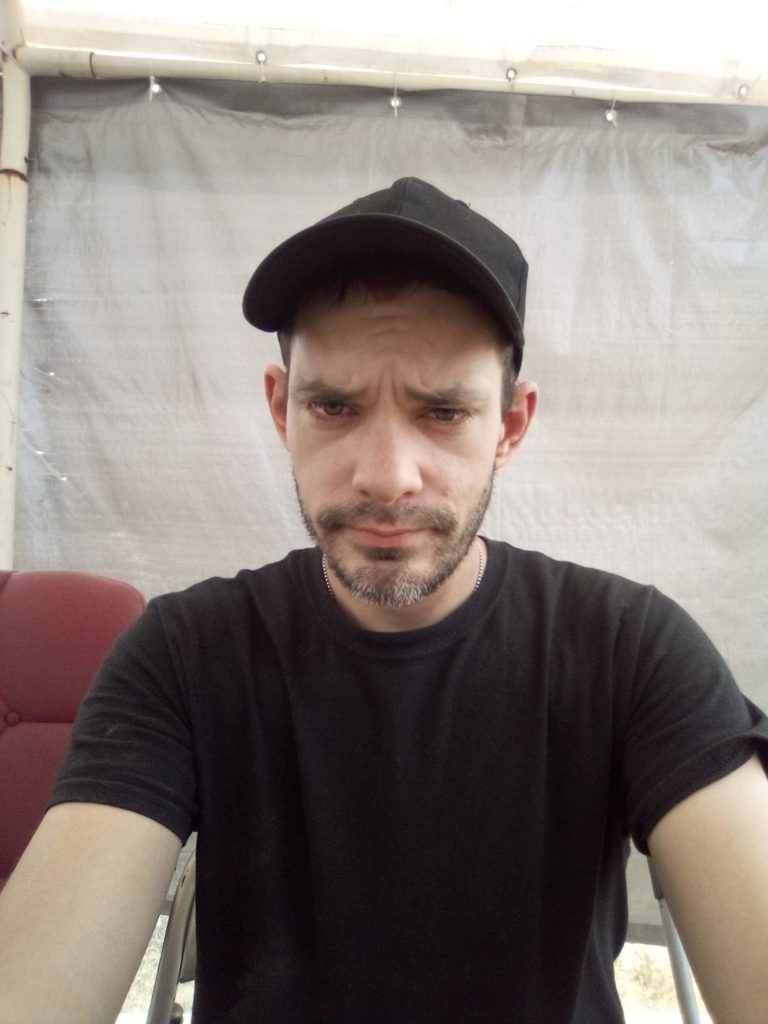

Kaitlyn Mason will always remember Stephen Vest as “the first boy I ever loved.”

She first met him when she was 5, and the pair grew up together and dated for two years while attending Paradise High School. They went to junior prom as a couple and, relying on Vest’s mechanical skills, together rebuilt a 1953 Ford Customline. Every weekend during the summers they dated, they went to car shows at Paradise’s Izzy’s Burger Spa, and Mason said Vest was like an older brother to her younger siblings.

The two remained friends in the decade-plus since their youthful romance, right up until the night of Oct. 14, when Vest was shot dead outside Petco during a confrontation with Chico police officers. Mason and others who knew Vest, 30, are having a hard time equating memories of their soft-spoken, gentle friend and the man who law enforcement officials say threatened passersby and charged officers with a knife before Sergeant Nick Bauer and officer Tyler Johnson opened fire.

Some of Vest’s friends and social service providers who met Vest, as well as local police-reform advocates, also question whether the killing of Vest—a Camp Fire survivor who endured childhood trauma, homelessness and possibly addiction and mental illness—was necessary. As with the 2017 CPD killings of Desmond Phillips and Tyler Rushing, Vest’s death reignites questions about the department’s use of force, crisis intervention and deescalation training.

A hard life

“He’s a sweet soul, a really kind person … even though he was very sad,” said Mason as she spoke about her friend by phone from Portland. “He always had a really hard life. He was very depressed, and I think he had some mental issues that got worse after high school.”

“Sweet,” “kind” and “sad” are words that came up again and again as friends spoke about Vest.

Everett Krieger said Vest was one of the first people to reach out to him when Krieger moved to Paradise in sixth grade, and that he’s considered Vest his best friend for the past 17 years.

“He lived on Pentz Road and I lived on Pearson,” Krieger said. “We lived less than a mile away from each other for most of our lives, and he was at my house all the time. We both knew each other’s entire families.”

Krieger explained that Vest’s life was mired in tragedy from a young age. Vest’s father, William “Bill” Vest, died just days after Christmas in 2002, when Stephen was in junior high. Krieger said Vest’s mother was not in the picture. Stephen lived with his grandparents following his father’s death and was very close to his grandmother, Helen Vest, who passed away in 2008.

Alyson Hubbard said she came to know Vest after high school and has been friends with him for about a decade. She and Vest were members of a tight-knit group of about a half-dozen friends who frequently hiked and camped together. Though the group has hung out less often in recent years—last gathering all together in 2016—they’ve kept in touch with one another. That included Vest, whom Hubbard spoke to a few months ago. In the group, Vest was known as “Stevo.”

“Stevo always marched to the beat of his own drum,” Hubbard said. “He was always funny, like he’d drop these one-liners. He was also pretty quiet, mellow and kept to himself.

“He had a really rough upbringing,” she continued. “He lived with his grandpa, and they never had much, but [Stephen] was always generous and willing to share whatever little he did have.”

All of Vest’s friends who were interviewed said he was prone to bouts of melancholy.

“If he ever got angry or upset he’d just be by himself, he’d never lash out or show anger,” Hubbard said. “He’d sometimes go through stages where he’d just disappear and not talk to us for a few weeks, but then he’d always come back and be just fine. We always wondered if there was something more going on there, some type of mental illness.”

Vest’s friends said his life became even more complicated in recent years. His grandfather, William Vest, Sr., died in 2016, and Krieger said Stephen was largely estranged from other members of the family. He first experienced homelessness then, but continued living in his grandfather’s home off-and-on until the house was destroyed during the Camp Fire in 2018. Aside from the occasional stint couch-surfing at friends’ houses, Vest mostly lived on the streets of Chico, sometimes staying at the Torres Community and Safe Space Winter shelters.

All of Vest’s friends who spoke to the CN&R said they remained in occasional contact with him since the fire, and that Vest often expressed frustration at the obstacles he faced while trying to get back on his feet.

Mason said Vest reached out to her after the fire and expressed remorse that—having herself lost everything in the fire—she couldn’t do more to help him then. They last communicated in May 2019, and Mason said Vest “told me he felt like he was being publicly shamed in Chico” for trying to obtain services and that he was still struggling and homeless.

“He told me about his mental problems and that he wasn’t able to get help,” she said. “I just feel like the system failed him over and over again.”

Vest vented in a March 5 Facebook post in which he apologizes to friends for being out of touch and expressed his frustration with endless paperwork, feeling dehumanized and other barriers to acquiring food stamps and general assistance.

“So stressed out I can barely take it … to the point of almost [mental] collapse,” Vest wrote. “Do I have a pulse? Do you even hear me? Echoes. So cold … wet … [where’s] the sun?”

‘He didn’t have to die’

Local police watchdog group Justice for Desmond Phillips has issued several statements decrying Vest’s killing and criticizing how such incidents are investigated. Currently, Butte County District Attorney Mike Ramsey oversees the Officer Involved Shooting Protocol Team, which is now in charge of the investigation. With the exception of Paradise police officer Patrick Feaster (who served half of a 180-day sentence for manslaughter after shooting Andrew Thomas in 2015), Ramsey has declared every other officer justified in the dozens of critical incidents he’s overseen since assuming the role of district attorney in 1987.

An Oct. 18 statement from J4D reads in part: “The police and District Attorney lied about what happened to Desmond and we have no reason to believe they would tell the truth about Stephen Vest. This is a general reminder that committing public executions is not part of the police officer job description. If you truly believe in the law and the legal system then you should be outraged by these killings.”

In an Oct. 19 press release, Jill Bailey of Concerned Citizens for Justice (CC4J) poses several questions about the incident, including asking what deescalation techniques were used, if the officers’ safety was endangered by the knife Vest wielded and, “Would the outcome have been different if the Behavioral Health Intervention Team had been present?” The group is calling on city leaders and Chico Police Chief Matt Madden to ask the California Attorney General’s office to investigate the shooting.

“Chico needs an impartial and transparent investigation,” the CC4J release reads.

Critics of Vest’s death cite his previous encounters with law enforcement—including on March 6, when police allege he assaulted a woman and he was charged with battery for biting an arresting officer on the leg—as cries for help and evidence that police knew about Vest’s mental condition.

“He had a history of mental-health issues and just like Desmond, he deserved help and support,” the statement from J4D continues. “Based on what we know so far, just like Desmond, Stephen has tried to get professional help for his mental health and the Butte County public services were failing him. He may have been acting out in a desperate attempt to be committed to inpatient care because he could not get help otherwise. We don’t know for sure all the details but what we do know is that both Desmond and Stephen were deeply loved by many and deserved metal health support and to be given a chance to get better.”

Lisa Currier, founder of Crisis Care Advocacy and Triage—a non-profit group that provides wrap-around services for people struggling with homelessness and mental health issues—met Vest while he was a guest at Safe Space Winter Shelter, and described him as “a quiet, gentle guy. He was awkward and overly polite. … He wouldn’t speak up and kept his head down.”

Currier called Vest’s decline and death a result of “a systemic crisis in the way we address mental health.”

“I’m tired of the lies we keep hearing that everything is working fine, or that Chico Police has enough officers trained [in crisis intervention] when they don’t,” she said. “I mean, there’s three officers there when they met Stephen and two of them have to unload their clips? It’s inexcusable.

“He’s obviously been arrested before and obviously had issues,” Currier said. “He wanted and needed help, was crying out for it, and no one replied. Or, they just locked him up for a couple of days and then sent him back out with no follow up or help. We need accountability, and we need to bring mental health to the forefront.”

More than a victim

Three days after Vest’s death, Mason said she still couldn’t bring herself to read through articles or watch news segments about the shooting, but said she’d heard all of the details from her mother.

“I made the mistake of reading some comments [on social media] though,” she said. “People are mean.”

“I never would have saw this coming,” she said, “and especially how excessive it was. It seems way too much for what was going on. I know he had a knife, but he was shot six to eight times. Why couldn’t they have stopped him some other way? They didn’t have to kill him.”

Hubbard and a few other friends are organizing a celebration of Vest’s life to be held at Saturday (Oct. 24) at 1 p.m. at Bille Park in Paradise. She said it will be an informal affair offering friends the opportunity to remember good times with and happy memories of “Stevo,” rather than focusing on his violent death.

Hubbard said she’s giving the officers some benefit of doubt, but she also questions her friend’s death: “In my opinion police are human too, and I’m sure the investigation will determine whether it was right or wrong,” she said. “But this was still someone’s life, and when it happens to someone you’re close to it gives you a whole different perspective.

“The lack of deescalation means he’s not here anymore,” she continued. “I’m sure [the police] probably tried, but in the end Stephen is still gone.”

Krieger pulls no punches in criticizing the use of lethal force. He said Vest is the second of his close friends to die at the hands of Butte County law enforcement officers; he also knew Andrew Thomas.

“I really wish they would have deescalated, tried to talk to him, used non-lethal force, anything,” Krieger said. “I detest how they’re depicting him in the news right now. He was a nice kid, he had issues, as everybody does.

“I wish they would have just reached out, talked to the kid … because that’s what Stephen really was. After everything he’d been through growing up, he was a sad, scared kid.”

Knowing the Officer that received a bite in the leg from Vest, he did deescalate him and they were having a conversation when his back up pulled up. He then became aggressive and violent. They were just trying to calm him down and keep him from hurting himself as well as them.

When I heard the two officers who had to shoot Vest, i was shocked as i know them personally as well and that is the last thing they ever would have done if they weren’t threatened. ‘

I would be curious if Steven Vest had any Narcotics in his system which could be a reason he was so aggressive and the fact that tasers didn’t effect him at all.

Stephen was a good friend of mine, he was staying with me 2 years before the fire. He helped me when I needed it most. He was always polite, respectful, if you needed help he’d be there. Yeah, he was very sad sometimes depressed. But he always found a way to make me laugh.

I will miss you very much my friend. Give Bear and Lizzie hugs for me….