As Kurt Albrecht walked among the rows of his family’s apricot trees on a recent blustery morning, parched, yellow grass crunched beneath his boots. There’s no longer any irrigation nourishing this orchard, but the small orange fruits hung from the boughs above him, ready for harvest, “due almost entirely to our weird rainfall this [May],” he said.

Next year, it’s likely these trees—20 acres of apricots, cherries and peaches, some that have been there for 50 years—will no longer exist at Chaffin Family Orchards, Albrecht told the CN&R.

Albrecht and his wife, Carol Chaffin Albrecht—third-generation owners and operators of the farm—are in a tough spot. The Miocene Canal, the primary water source for their 2,000 acres of orchards and cattle pastures in Butte Valley, has run dry since Nov. 8, when the upper portion of it—otherwise known as the Paradise flumes—was destroyed by the Camp Fire.

Photo by Ashiah Scharaga

Kurt Albrecht, of Chaffin Family Orchards, examines the farm’s apricot crop. Next year, it’s likely the family will have to let 20 acres of stonefruit trees (including the ones pictured) die if there is no water flowing in the Middle Miocene Canal.

If they remain without water, the Albrechts will have to sacrifice those stone fruit trees. The couple’s 200 acres of century-old olive orchards, their primary crop, can handle going dry this year, but how they will fare is uncertain.

For example, if a hot summer gives way to a relentless fall, Albrecht said, come harvest time there could be no olives to pick and press for oil.

“It’s definitely going to translate to less product, but it also makes it very difficult to plan and have any predictability in crop sizes … which relates to gallons of oil, in our particular case,” Albrecht said.

The Miocene Canal has a rich history. Its roots go back approximately 150 years. PG&E has owned portions of the canal since 1917. This year, however, the utility giant—filing for bankruptcy and finding itself culpable for the deadliest and most destructive fire in state history—announced it would not repair the system. This is due to the cost—the utility estimates a price tag of at least $15 million.

It’s a devastating turn of events not only for the Chaffin family and the two dozen other contracted water users—including ranching and farming families that relied upon the Miocene for generations—but also for many other residents and wildlife in this rural stretch of Butte County. The system’s water has sustained thousands of acres of ranch and farm land throughout its history.

Several landowners have reported that their wells, streams and ponds are now drying up. As a result, some have spent thousands of dollars to purchase water tanks and have water delivered. But it still isn’t enough to support their livelihoods. Orchards are going dry, livestock are being sold or moved.

A group of concerned property owners have joined forces, forming the Miocene Canal Coalition and advocating for restoration of water to the Middle and Lower Miocene, which were not damaged in the fire. While Butte County has assembled various agencies to discuss short- and long-term options, nothing concrete has emerged.

In the meantime, landowners are devising ways to get through the summer. Chaffin Family Orchards, for example, can draw from a private reservoir to provide water for cattle and irrigate citrus trees, which otherwise would not survive.

“We’re going to try to spread water too far, too thin to stay viable for a long-term sustainable plan [of] operation,” Albrecht told the CN&R. “Financially, it’s devastating. … We’re having to tap [family savings] in order to get through this year.”

Miocene history

The Miocene Canal is a byproduct of California’s Gold Rush era. The 25-mile-long, man-made infrastructure—a system of ditches and wood-supported metal channels—was originally created in the late 1860s or early 1870s by the Miocene Gold-Mining Co., which owes its name to the Miocene Age, when basalt flows covered up placer deposits in eastern Butte County and beyond. The flumes diverted the Feather River so miners could excavate, according to the “Miocene Ditch” edition of Diggin’s, the Butte County Historical Society’s magazine, published in 1983. Gold miners were the first water-system builders in the Sierra Nevada foothills: It is estimated that over 8,000 miles of ditches were constructed at the height of hydraulic mining, which used canal systems to pressurize water and direct it against banks of gravel that would then disintegrate and wash over sluices.

Photo courtesy of Scott C. Shaw

A view from a destroyed section of the Upper Miocene Canal east of Adventist Health Feather River Hospital off of Pentz Road in February.

In the late 19th century, these systems started being used for hydroelectric power generation. The Oroville Water, Light and Power Co. (known later as the Oro Electric Co.) purchased the Miocene, constructing a head dam in the west branch of the Feather River Canyon, east of Magalia, in 1909. This water flowed down the Upper Miocene, then into Kunkle Reservoir off of Pentz Road before winding through the turbines at the company’s Lime Saddle Power House, built in 1906. From there, the water moved through the Middle Miocene, flowing southwest through Butte Valley, where it reached the Coal Canyon Powerhouse, built in 1907, and entered the Lower Miocene, a part of the conveyance system that runs roughly parallel to Highway 70 before reaching the Cherokee Reservoir.

PG&E purchased the Miocene and both powerhouses in 1917, including the water delivery system for Oroville, according to PG&E spokesman Paul Moreno. Ten years later, the company sold the Oroville water system, including the Lower Miocene, to what later became California Water Service Co., which owns that section to this day and has a contract to purchase water from PG&E.

Moreno told the CN&R that PG&E performed annual maintenance and repairs on its portion of the canal, shutting off water temporarily for those efforts: Most years, according to families the CN&R spoke with, PG&E gave farmers and ranchers notice so they could store water. The utility would shut the canal down during the rainy season, in early spring, for about four to five weeks, so it would have minimal impact.

Many of the property owners adjacent to the canal, like the Albrechts, have purchased water from PG&E for so long their contracts are written in miner’s inches, a measurement of water representing flows through miners’ sluices.

Two years ago, PG&E put its portion of the Miocene Canal system and powerhouses up for sale. Moreno explained that, in the company’s view, “the value of the power generation doesn’t really cover the cost of running and operating the system.”

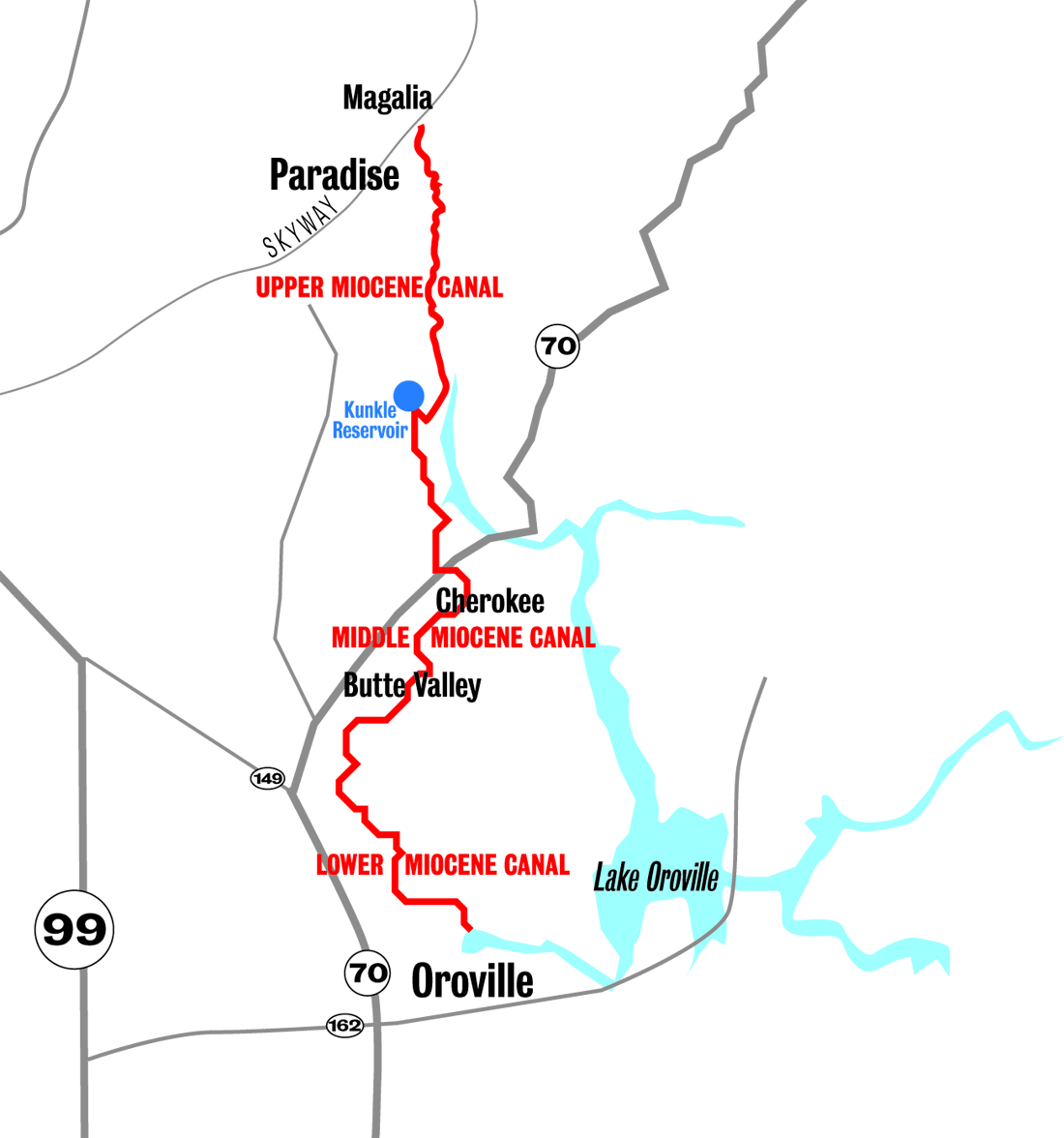

Map by Tina Flynn

The Miocene Canal (shown in red) spans 25 miles, from Magalia to Oroville.

PG&E had a potential buyer before the Camp Fire destroyed the Upper Miocene. Washington-based Tollhouse Energy Co. still is interested, company engineer Adam Cleveland said at a recent public meeting, but needs “to determine if it would make economic sense for us.”

Moreno told the CN&R that water rights could be part of a sale but would not disclose further details.

A coalition emerges

Members of the Miocene Canal Coalition have been pressing PG&E since the fire and in April took their concerns to the Butte County Board of Supervisors.

Ed Cox, the group’s spokesman, has argued these main points: The canal is a historical landmark that should be repaired and preserved, and its water feeds Kunkle Reservoir and ponds downstream that are an invaluable resource for fire suppression, as well as habitat for wildlife, including imperiled species (the latter has been debated—see “Where the wild things aren’t,” page 19).

Per the direction of the supervisors, Paul Gosselin, director of the county’s Department of Water and Resource Conservation, essentially has served as a mediator between PG&E, Cal Water, the coalition, other water users and providers. However, because the canal is privately owned, there’s not much more the county can do to steer the outcome. County Counsel Bruce Alpert said as much at a supervisors meeting in late April.

“We can’t tell PG&E what to do with [the Miocene Canal] or what water to take into [it],” Alpert said. “It is up to individual landowners, unfortunately, in this situation to hire counsel to take whatever action they deem appropriate or they think they have a right to take.”

Earlier this month, the parties assembled and attempted to carve a path forward during a three-hour meeting at the Feather River Tribal Health auditorium in Oroville. It was the first gathering at which water users were brought to the table with representatives from PG&E, Del Oro Water Co., Paradise Irrigation District (PID) and other stakeholders to hash things out.

It was at times a tense exchange—frustration and fatigue were evident as coalition members pressed PG&E and Cal Water for answers periodically throughout the meeting. Every time, their representatives offered a similar reply: They understand and were there to be a part of the solution. However, they didn’t offer specific ideas. PG&E representatives did confirm that the company would not repair the Upper Miocene, and had not considered building a pipe to get water flowing into the Middle Miocene from nearby Lake Oroville, as water users have suggested.

Former county water commissioner John Scott, a longtime advocate for groundwater protection in Butte Valley, was the first to address the elephant in the room: “The people that burned the Miocene Canal down … and who had obligations to a lot of people sitting at these tables should be coming to the table and telling us what they’re going to do other than just saying, ‘We’re out of here.’”

Gosselin quickly interjected: “Some of us have different lawsuits against some of the people around the table, but we’re … going to keep it focused on … solutions,” he said.

When it was their turn to take the floor, many landowners shared stories similar to that of the Chaffin family: facing uncertain crop yields, moving livestock temporarily, paying exorbitant prices to truck in water.

Photo by Ashiah Scharaga

Paul Gosselin, director of Butte County’s Department of Water and Resource Conservation, has served as a mediator of sorts in discussions between water users and PG&E—it is the county’s goal to help the region retain surface water rights that have historically flowed through the Miocene Canal.

Cattle rancher John Crowe said the latter is just not affordable to sustain operations. “You could burn the Butte County roads up all you want … but it’s not going to irrigate olive orchards … hauling water is not in the cards. Hauling water is for flushing toilets,” he lamented.

Toward the end of the meeting, a few possible solutions were discussed. Del Oro is researching the cost of drawing 20 acre-feet per day from Lake Oroville, which would be enough to return flows down the length of the Middle and Lower Miocene.

PID, Del Oro and PG&E also are exploring a partnership to use existing infrastructure shared by PID and Del Oro to get water flowing into Kunkle Reservoir. But both face capacity challenges when it comes to providing enough water to the Miocene, and it isn’t cheap for the companies to purchase water from PG&E.

In the meantime, the coalition pressed PG&E on its contract language, arguing that the company had promised to deliver water in emergency situations such as this. Moreno told the CN&R later that PG&E “is happy to discuss” water delivery with its contracted users.

There could be funding available through grants as well. The U.S. Department of Agriculture can provide funds to help property owners dig wells, put in storage tanks and stock ponds. There’s a caveat, however: because the foothills rest on fractured rock, not in the basin, well-digging is “a lot less reliable” and “unpredictable,” Gosselin said. Grant funding is available to deliver water to low- to moderate-income families, according to Casey Hatcher, county spokeswoman.

What it boiled down to for the water users, however, is that they don’t see a path forward that doesn’t involve refilling most of the leaky Miocene because of the streams, ponds and habitat it has created and supported for more than a century.

What comes next?

A second meeting with the agencies and water users has been scheduled for mid-July. The county has applied for several “planning grants,” Gosselin said, which could fund research on the environmental impact of the Miocene and, once solutions are identified, could inform the best way to proceed with applications and ideal funding sources.

Photo by Ashiah Scharaga

Laura-Lyn Burch stands before two water tanks the family installed after a 2016 fire took the Miocene offline for six months.

“It does look like some of the more immediate, short-term things are going to be pretty limited for this season. That’s the reality,” Gosselin told the group. “The system’s gone in and out [of service]—I mean you all know it—for a long time because of other fires and floods …. I think broadening the options for water supply is what we’re looking at for resiliency along the line. That’ll take some time and some creativity.”

Cattle rancher Gail Tozier reflected after the meeting, telling the CN&R she appreciated seeing so many agencies willing to attend and participate with a “genuine desire” to come up with solutions. But in reality, she said, nothing came out of it. “They need to realize really and truly the only viable solution is to recharge the canal,” she said.

Tozier lives just up the road from Chaffin Family Orchards. Her family has operated Tozier Ranch across 275 acres, raising cattle and tending olive orchards, for 16 years, but the property has been used for agriculture since the early 1900s.

The lack of water has impacted every aspect of her ranch’s operation and increased the cost of doing business, she told the CN&R. Like the Albrecht family, they have 100-year-old olive trees going dry this season with “no idea what’s going to happen” after a sweltering summer with no water. They already lost last year’s crop due to smoke contamination from the Camp Fire.

Additionally, they typically lease nearby property for their small herd of cattle but cannot this year because of the lack of water. They’re having to move the herd to less-than-ideal land—where they have to haul water and feed—and may have to sell some cattle because of the disruption it has had on calf weaning. They are using their domestic well to pump water to tanks they have purchased for the livestock.

“We’re just kind of winging it,” Tozier said. “I’m just hoping and praying there will be some solution where they can recharge the canal.”

Albrecht said if the family loses those 20 acres of apricots, cherries and peaches, they won’t replant until they know if or when water is available. Even if they get water back next fall, it’s not a quick turnaround.

“We’re looking at probably four or five years before we get significant harvest of [those trees],” he said. “We’d use the opportunities to change varieties, [that’s] probably the upside, but it’d be a lot easier to do that in small blocks of time, not to be forced, because there’s not new revenue … for a number of years.”

It’s a complete shift in operations, he continued. Then there’s the potential loss of the farm’s client base, who will now go out and find fruit elsewhere.

“It’s pretty difficult from a marketing standpoint. … We’ll lose those customers and have to find them again after we’ve regrouped,” Albrecht said. “For a long time, I always thought … if PG&E decided to turn the canal system off, they would write us a check … that we would be compensated for the loss of revenue.”

When asked what a second dry summer could mean, many property owners told the CN&R they would have no choice but to downsize their operations. Many, like Albrecht, said that they felt PG&E has a responsibility to make things right, or to compensate their families for the loss.

Tozier says so many people think of the canal for the recreational value it had for their families. Her kids and grandkids have enjoyed playing and walking near the canal and watching wildlife, too. But the bottom line is that the water is needed for irrigation and livestock.

“Everybody in our situation has felt somewhat guilty because we still have our homes,” she said, “but we’re still a casualty of the fire.”