Photo by Meredith J. Cooper

“This used to be lush forest,” says Calli-Jane DeAnda, executive director of the Butte County Fire Safe Council. She’d assembled a group of stakeholders to discuss the region’s future. From left: Eric Josephson, Ryan Bauer, DeAnda, Tim Snellings, Dan Breedon, and Peggy and Pete Moak.

Five-plus months after California's deadliest and most destructive wildfire wreaked havoc on Butte County's foothills communities, experts are still pondering a complicated, but critical question: How do we avoid another Camp Fire?

The answers are far from simple. But for the two dozen local stakeholders who got together April 4 in Concow to survey what's left of that community, one thing was certain: Whatever we do, we must abandon the status quo.

The group, assembled by the Butte County Fire Safe Council, represented a wide range of local experts—from Cal Fire, the U.S. Forest Service, the Butte County Resource Conservation District, the Konkow Maidu tribe, among others—who, together, possess a vast amount of knowledge and experience when it comes to fires, the landscape and topography, and planning.

They gathered in Concow because of the historical context it provides. It has, after all, burned before—most recently during the devastating Butte Lightning Complex fires of 2008. Strangely enough, the blaze that leveled Concow that time also was dubbed the Camp Fire. So history does have a way of repeating itself. Had wind conditions mirrored those of last Nov. 8, the day the 2018 Camp Fire ignited, Paradise may have seen destruction a decade earlier as well.

“This is one of the largest high-severity burn zones in California, one of the most devastated ecosystems in our state,” said Calli-Jane DeAnda, executive director of the Butte County Fire Safe Council, who was leading the day’s discussion. “The Camp Fire was the deadliest and largest fire—and I think Concow has [taken] the brunt of that ecologically. We are all dealing with something that has never necessarily been tackled before.”

“This used to be lush forest,” DeAnda explained. “But the ’08 fire burned so much, and the Camp Fire burned so hot, that now it looks like the Nevada desert.”

For the next four hours, the group identified problems that contributed to the recent Camp Fire—too much dead wood and brush, poorly planned communities, difficult terrain, climate change. The solutions weren’t clear-cut, but could be whittled down to a few key ideas: thoughtful planning of the wildland-urban interface (aka WUI, pronounced “wooey”) and continual maintenance of it, to include forest thinning and prescribed burning. Any solution will require partnerships that have, thus far, been difficult to forge.

Other fire-stricken regions of the state are dealing with similar scenarios on a smaller scale. So, while the group focused its discussion on the local landscape, they did so with the understanding that whatever the decision-makers do right now has much broader implications. Indeed, lawmakers and scientists across the state—and even the world—are watching and learning from what’s happening here.

DeAnda believes the first area of attack should be Concow, as the level of devastation in that community is so massive—before the Camp Fire, there were some 500 people living there; now locals count about 30.

“We basically have a clean slate, although there’s a lot of work to be done out here,” offered Eric Josephson, of the Konkow Maidu Cultural Preservation Association.

“Concow is part of what makes Paradise burn,” added Zeke Lunder, founder of wildfire consulting firm Deer Creek Resources, based in Chico. A pyrogeographer, he specializes in mapping and analyzing wildfires.

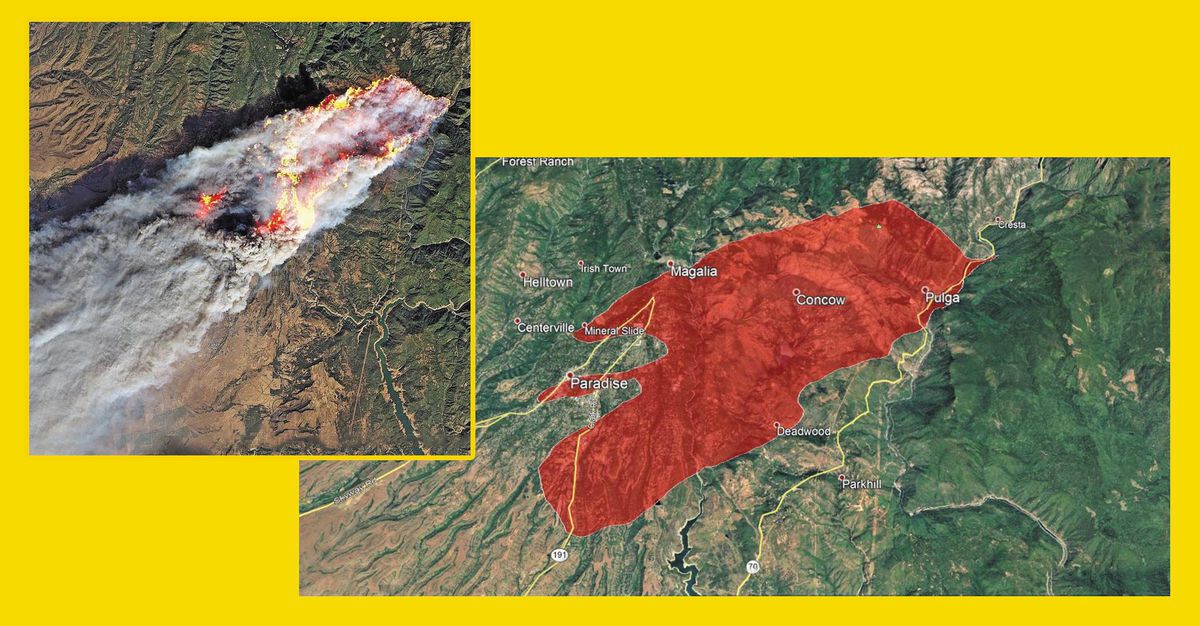

Maps courtesy of Zeke Lunder, Deer Creek Resources

The infrared map to the right shows the heat concentration of the Camp Fire, early on, while the satellite image (above) shows the actual blaze.

‘It’s burned here forever’

“Concow has burned the entire existence of my tribe,” Josephson told the group. “When Concow burned in history, two little boys went down into the sweat house and threw some pitch pine onto the fire. And it leaped up … and from there, it spread everywhere, killing all the Konkow but two.

“So, how’d we survive? Most of ’em didn’t! All but two died one time—at least, that’s the story from my tribe.”

But until 2000, the community had lived peacefully without burning for decades. On Sept. 19 of that year, a resident hit a rock in a crawler tractor and a spark set the dry grass ablaze, according to a Cal Fire report on the incident, dubbed the Concow Fire. That blaze destroyed 14 homes and spread over 1,845 acres. One woman refused to leave her dogs inside her house and died.

Eight years later, the Butte Lightning Complex fires—57 of them—were much more destructive. Sparked by lightning storms, they roared through the region, covering nearly 60,000 acres and destroying 212 residences, 50 of them in Concow, where again one civilian was killed. Dry weather and a series of lightning events across Northern California that summer were deemed responsible for a total of 2,000 fires spanning 1.2 million acres.

“In California’s modern fire suppression era, this many fires starting early in the season, and burning simultaneously over such a long a period of time is unprecedented,” a Cal Fire summary reads.

In both 2000 and 2008, incident summaries indicated that while the vegetation provided much of the fuel, homes and other buildings also contributed. As the frequency of fires in the WUI has increased, the need to enforce defensible space around structures has grown as well.

“It’s burned here forever,” Josephson reiterated. “People should know that and build accordingly.”

His wife, Kate Hedges, suggested looking at alternatives to wooden frames and even considering building semi-subterranean homes in the hopes that “the fire will just roll right over the tops.” Sticking with the old ways won’t work, she said, because that doesn’t take modern technologies or issues into account.

“We’ve gotta talk about climate change,” she said frankly. “We have to adapt or leave.”

Others echoed her.

“We had a fire in 2000, we had a fire in 2008 …. We have a lot of fire [here],” said Tim Snellings, director of development services for the county. “People and fire are not a good match. We have a planning discussion ahead of us …. It’s not just a reforestation, growth-stabilization process—we have a discussion about repopulation ahead of us. We need to have a serious conversation about that.”

Photo by Meredith J. Cooper

Pete Moak and his family successfully defended their home from the Camp Fire when it came through Concow. Part of that was because Moak clears the property religiously—with goats and prescribed fires.

Pete Moak, a Concow resident who, with the help of his family, successfully defended his property, along with the neighboring Cal Fire station, agreed. More than once, officials referred to Moak not as a landowner but as a “land manager.” So, beyond planning the community—including where people should and shouldn’t live—with the understanding that fire will inevitably return, it’s incumbent upon residents to work together to ensure the next fire is less ferocious and deadly.

“You need to be independent up here, to take care of yourself,” Moak said. “And that’s gotta be something—how do you tell people that they can’t take care of themselves? They retire somewhere, they come up into these beautiful areas. They want to enjoy the timber, the woods …. But in order to do that, you’ve got to be able to say to yourself, ‘Yes, I’m self-sufficient.’ A lot of ’em aren’t. They don’t have a clue. When fire comes that close, it’s a scary situation. And we had people die that weren’t prepared.”

Managing the landscape

After the fire rolled through in 2008, the U.S. Forest Service surveyed what was left on its parcels in the Concow basin, Ryan Bauer, a fire management specialist for the agency, told the group. They were standing in a rough circle on a patch of land along Concow Road overlooking the region’s reservoir of the same name. The landscape looked more like a moonscape, someone commented, to nods of agreement.

“The place we’re standing right now is national forest land. It was masticated after the 2008 fire,” Bauer said, referring to the mechanical process of chewing up brush to reduce fuels. “A 20-acre chunk of mastication in a sea of brush isn’t successful at doing anything. It didn’t perform. It burned how you expect a brush field to burn.”

In fact, on another USFS parcel, which is too steep to use masticating machinery, it burned exactly the same, he said. That’s because that process may cut down fuel—but it doesn’t remove it. Now, with an estimated 600,000 dead or dying trees in the Camp Fire burn zone, it’s imperative that those responsible for that land do something different, he said. First, the trees must be removed. Second, he said: prescribed burning.

“What we need to be thinking about when we think about fuels treatments is they need to be designed to put more fire on the landscape, to allow us to live with fire,” Bauer said. “Because we know it’s going to continue to happen.”

A century of aggressive firefighting has left the state of California with dense, and in many areas dying, forests. Bauer’s views on introducing fire to the landscape are shared by many across the state, as tactics have shifted in recent years toward accepting fire as a natural occurrence in nature rather than something to be suppressed. At the same time, people who have long fought against forest thinning are beginning to come to terms with the practice—for fire safety as well as wildlife and watershed protection.

“There is a paradigm shift occurring across the Sierra Nevada region which demonstrates that a diverse group of stakeholders, agencies and individuals recognize that the forest is overgrown and in jeopardy of continued catastrophic wildfires,” DeAnda told the CN&R.

Cal Fire Battalion Chief Gus Boston also understands the value of controlled burning, part of his agency’s strategy for combating wildfires. As head of the Butte Unit’s vegetation management program, however, he took it a step further. He suggested forest thinning projects—like two in Magalia managed by the Fire Safe Council, which have been credited with slowing the Camp Fire’s spread.

“There was also work completed last year at the Pine Ridge School in Magalia, which was very helpful in firefighters’ ability to protect the school during [the] Camp Fire,” DeAnda told the CN&R.

Boston also emphasized bringing in plant species that will protect the landscape versus allowing whatever is now growing—or might sprout naturally—to flourish.

CN&R File Photo by Meredith J. Cooper

This photo was taken overlooking Concow Lake two months after the Butte Lightning Complex fires in 2008.

“There was standing timber here that survived the 2008 impact—that no longer exists,” Boston said. “Now you can see, overall, the landscape has completely changed. There are some places that had a timber fuel component, and that’s now gone. What’s going to come in behind it? That’s what we’re concerned about.”

To avoid allowing the accumulation of dead trees and brush—perfect fuel for a fire—as was the case pre-Camp Fire, everyone agreed, there must be a combination of either mechanical mastication or livestock and prescribed burns. Moak, whose house the group visited as a prime example of how to survive a blaze, uses goats and fire to keep his property clear.

“Possibly we haven’t had enough fire [in recent years],” he said. “Because in the old days, they did burn it. Intentionally. Maybe we need to plant trees that can withstand that. And have slow-burning fall fires, with cattle grazing and livestock grazing ….”

Goats have become increasingly popular in culling tough brush like manzanita, which grows rapidly and burns well. Plus, Moak added, they stamp down the ground while they’re munching.

“You can see it, right down on Concow Lake, where they did have goats this last summer, they grazed all of Concow Road along [there],” he said. “It didn’t burn.”

What’s more, at least one person with property by the water was able to survive the fire by jumping into the reservoir. He wouldn’t have been able to do that if the woods there had been overgrown, Jim Hautman, of the Fire Safe Council, told the CN&R.

“If we look at the history of what we’ve accomplished with cutting brush, as far as affecting the size of the fires we’ve had, we haven’t been effective at all,” said pyrogeographer Lunder, in addressing the bigger picture of how fire moves through the landscape. “There are scant opportunities for a fuel break to be effective. And, when the wind’s blowing, there’s no opportunity for a fuel break to be effective.

“We can’t really vegetation-manage our way out of the problem. Fire belongs here and we need to live with it,” he added. “We need to start with not making the problem worse when we come and clean up after it.”

Everyone agreed that no one approach will solve the problem of vegetative fuel in the Concow basin, particularly when considered within the bigger context of the vast forests that surround it. Going forward, DeAnda said the group had formed a Forest Health and Wildlands Task Force Committee, which plans to meet next on Wednesday, April 24 (see infobox).

“This is a very large project,” Boston said. “What we do in the next 36 months with that vision is going to be how this landscape unfolds in the future.”

All together now

One of the biggest obstacles to putting together a large-scale effort such as improving the fire safety of Butte County’s communities and forests—as well as putting them in the larger context of California and even the nation—is the fact that no one entity oversees it all. In Concow alone, portions of the land are owned by private citizens like Moak; by Native American tribes like the Konkow Maidu; by governmental bodies like the U.S. Forest Service; by private corporations like Sierra Pacific Industries; and by special districts like Thermalito Water and Sewer District, which owns Concow Lake, and Paradise Recreation and Park District, which owns the nearby Crain Memorial Park.

Photo by Meredith J. Cooper

Cal Fire Battalion Chief Gus Boston (left) and Ryan Bauer, a fire management specialist with the U.S. Forest Service, discuss how to manage the landscape in Concow after the Camp Fire.

So, how to get everyone on the same page, and who should be in charge? Those are additional questions stakeholders have been asking themselves—and having fits over. Large agencies often have the ability to get grant and other funding to do projects, but without partnerships with nonprofits and other boots-on-the-ground types, well-intentioned plans tend not to get implemented, the group agreed.

“I’m sick of planning for the sake of planning,” Lunder said.

John Hunt, conservation manager for the Northern California Regional Land Trust, echoed him.

“When you’re talking about reliance upon agencies or, rather, the relinquishment of our obligations or responsibilities, etc., [to agencies]—it creates a bottleneck,” he said. “Essentially, agencies … are driven by these large bureaucracies with point people. And our communities are loaded with people who are badasses—they’re knowledgeable, they’re experienced—who are underutilized and underintigrated.”

Any plan that has a chance of meaningful, timely follow-through “has got to be led by people in the community who … have the experience,” he continued. “And it has to be enabled, it has to be empowered. It can’t be just left up to the agencies.”

Moak piped in: “We can have the knowledge on the ground, but we can’t do the paperwork,” he said, referring to processes like applying for grants that take time and expertise.

One tool that will soon be available to address those constraints comes from a watershed grant just obtained by the Butte County Resource Conservation District—a special district whose mission is to “protect, enhance, and support Butte County natural resources and agriculture” by working with public and private landowners. The grant will, in part, help launch a local prescribed burn association (PBA). The concept is fairly new—only Humboldt County has an active PBA, though Plumas recently launched one, too—and would provide support for partnerships between public and private entities, plus work- and equipment-share opportunities.

“So, someone like Pete [Moak], who has a lifetime of knowledge—it will allow people who aren’t Pete but want to be like Pete get the backup support they need,” explained Wolfy Rougle, conservation project coordinator for the district. “It’s not fair to just expect normal people to volunteer forever. There needs to be … some framework for people to fall back on, a place to park the trailer with the gear in it.”

Legislation is being crafted to help individuals become certified in prescribed burns, Lunder added, because the idea of having private citizens perform risky maneuvers is a scary prospect if they’re not fully confident and trained in what they’re doing. The grant, Rougle said, hopefully will get the ball rolling.

DeAnda, of the Fire Safe Council, also has an idea she hopes to implement sooner than later. It requires participation from public- and private-sector stakeholders and would empower them all.

“I feel like the next big thing that needs to happen is to have a collaborative map that everybody can be working off of,” she said, speaking specifically in regard to Concow. “It would show, at parcel-level, where the burn severity was the highest, where we’re anticipating the most brush regrowth, where we would want to replant oak versus conifers, where we would need strategic fuel breaks, where we want to have cultural information—just the go-to vision going out 10 years in the future.

It would encompass “the bulk of the WUI,” she continued, “everything we see here where homes used to be that’s going to be influenced by fire.”

The county should look at zoning to reduce population density—which could save lives while reducing fuel on the landscape—and also consider mandates regarding defensible space, some suggested. Fines for noncompliance, and even a lien process, could improve the entire region’s ability to avoid future catastrophic blazes.

In looking at the bigger picture of how the USFS and other agencies can learn from the fires in Concow, Bauer summed it up: “We’re going to have to accept that we’re going to have large, long-duration wildfire events in there that are actually going to ultimately benefit the landscape. Because otherwise we’re setting up a situation where we’re keeping fire out of there for 50 years and then the big one comes rolling down the canyon.”