By Alejandro Lazo & Jeanne Kuang (for Cal Matters)

CalMatters is an independent public journalism venture covering California state politics and government. For more info, visit calmatters.org.

California faces a projected deficit next year even if the U.S. avoids a recession. Despite the expected shortfall, policymakers say they’ll maintain spending on social programs though advocates are calling for more.

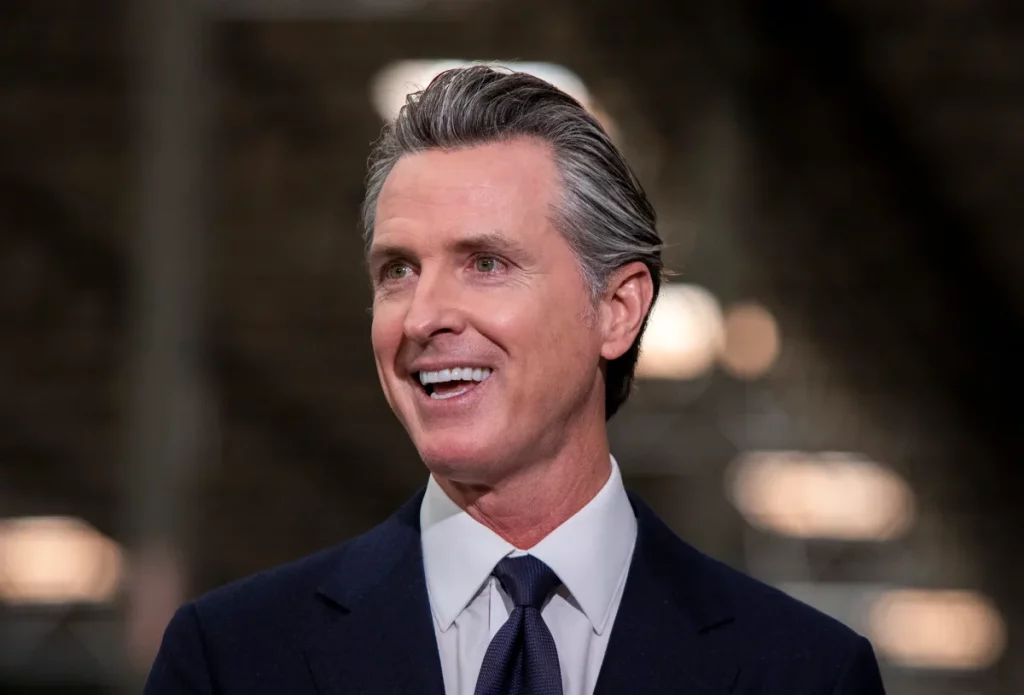

The Legislative Analyst’s Office recently said in its annual forecast that Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Democratic Party-controlled Legislature are facing a $24 billion projected budget deficit for the next fiscal year.

If the state enters a recession the outlook is even worse, with revenues predicted to fall short by $30 billion to $50 billion. The governor signed a record-breaking $308 billion budget in June.

The legislative analyst attributes the projected shortfall to California’s reliance on those whose incomes often ebb and flow with the price of stocks, real estate and other investments.

“Those are the same people who get a lot of their income from financial investments,” said Legislative Analyst Gabriel Petek. “That volatility then gets transmitted directly to the state budget.”

The governor will present a proposed budget in January and then a revision in May. The budget, which the Legislature must approve, will fund state government for the fiscal year beginning July 1.

H.D. Palmer, spokesperson for the state Department of Finance, declined to comment on whether social spending cuts might be proposed.

He did say, however, that the governor’s priority was to not scale back programs that people have come to depend on, or to begin new ones. Some program expansions in later fiscal years could be delayed if there isn’t enough revenue to support them, he said. The goal is to avoid the kind of drastic program reductions enacted during the Great Recession that took years for the state to restore.

Building reserves

The state’s Democratic legislative leaders have said they are not inclined to cut recently expanded programs, such as the extension of free health care to low-income undocumented immigrants, which began with older adults this year and is slated to open up to all ages in January 2024. The expansion is expected to cost more than $2 billion annually.

The budget is in a much stronger position than it was during the state’s last fiscal crisis, said Phil Ting, the Assembly budget committee chair from San Francisco.

“We have a significant amount of cash available, both in terms of reserves, but also in terms of liquidity,” Ting said. “So this is a very different situation than the state faced in 2008-2009, where they were running out of cash.”

The governor, nevertheless, has signaled he is being cautious. Newsom in October said he had vetoed 169 bills and saved taxpayers billions. Seventy-five of those vetoes were directly budget related, with many including boilerplate language that the state was facing “lower-than-expected revenues” and that it was “important to remain disciplined when it comes to spending, particularly spending that is ongoing.”

Among the bills vetoed by the governor earlier this year were proposals to expand government-funded care for new mothers, expand free transit programs for California students and create grants for graduate students in mental health who commit to working at certain California-based nonprofits.

Newsom, whom voters elected to another four-year term, has used surpluses to pay down debts, build reserves and provide direct payments to millions of Californians.

Recently Moody’s Analytics rated California one of the states most prepared for a recession, citing its reserves.

Nevertheless, California’s budget enacted in June 2021 committed to $3.4 billion in new ongoing spending and is expected to grow to $12 billion in the 2025 budget year. The budget enacted in June of this year committed an additional $2.3 billion, expected to grow to nearly $5 billion by the 2026 budget year, the Legislative Analyst’s Office said.

The state has $37 billion in specific reserve funds. That includes about $23 billion in a rainy day fund voters agreed to strengthen in 2014 at the urging of then-Gov. Jerry Brown. The state also has $900 million in a reserve account for safety net programs. The rest of those reserve funds are in school-specific and general operating reserves.

But, Palmer noted, the state can only draw down the rainy day fund by half in any year. The Legislative Analyst’s Office has advised the Legislature to slow down or pause program expansions before dipping into reserves.

Ting’s office contends the state has billions in unspent federal and state dollars in its coffers that could address a potential deficit. Using that money would avoid cuts to programs but delay other projects.

Is it time to spend?

Anti-poverty advocates said in interviews they plan to continue pushing for program expansions, arguing the precipice of a downturn is the time to bolster social spending, not cut it.

Nearly 30 percent of California residents live in or near poverty, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. Experts expect poverty rates to increase after the end of a boost in federal cash aid, which came in 2021 in the form of an expanded child tax credit included in the American Rescue Plan Act.

Advocates are proposing that California mimic that federal expansion by opening up the state’s Young Child Tax Credit, currently a $1,000-a-year credit for low-income families with children under age 6, to include all children in low-income households.

They estimate 1 million children live in families that would qualify, at an additional cost of $700 million a year.

Additional tax credits could make a difference to people like Ivonne Sonato-Vega, a medical assistant in Santa Rosa.

Last year she used some of the $4,000 in federal child tax credits on school supplies and clothes for the four children she and her boyfriend are raising, she said. With prices rising this year, she was unable to save any of that subsidy.

If the credits were an annual payment, she said, it would allow her to plan for expenses, maybe use it as “a little savings account” to draw on when the children grow out of their clothes or save it for a security deposit if the family needs to move.

“It was kind of like a tease,” she said of the credit. “It was here and then not.”

Advocates said they also want the state to create an unemployment benefits program for undocumented immigrants and to include all low-income immigrants, regardless of immigration status, in its food assistance program.

“We know the projected budget shortfalls make it more challenging, but the past few years highlighted why something like this is so important,” said Sasha Feldstein, economic justice policy manager at the California Immigrant Policy Center. “People who are excluded from our safety net have been the most adversely impacted from the COVID-19 pandemic and are the most harmed during times of economic downturn.”

Lawmakers and Newsom this year allocated money to expand the California Food Assistance Program, a state version of food stamps, to include undocumented immigrants age 55 and older; the benefits are expected to become available late next year. Newsom vetoed a bill that would have tested an unemployment benefits program for undocumented immigrants, citing costs.

The makings of a budget problem

The projected shortfall is the state’s first major fiscal challenge since Newsom’s office predicted a $54 billion shortfall in May 2020, when the country was in the grips of the COVID-19 pandemic. After financial markets rebounded and the federal government provided unprecedented stimulus, the anticipated shortfall resulted in surpluses.

The Federal Reserve began hiking interest rates in March 2022 to cool inflation. Then housing sales, initial public stock offerings and stock markets fell. All are important sources of personal income tax revenue.

In California, personal income withholding fell even as the job market recovered.

Over the last decade, California has increasingly relied on some of the state’s highest earners to fund its budget which, among other things, takes aim at poverty and some of the nation’s starkest income inequality.

Much of the state’s general fund is paid for by its progressive personal income tax, which voters in 2012 raised on the state’s highest earners after Brown warned of cuts to health and education. In 2016 voters extended those higher income tax rates through 2030 while also allowing a temporary sales tax to expire. The increases, meant for education and healthcare spending, have also paid for increased social safety net spending.

About 49 percent of the personal income tax paid in California in 2020 came from just 1 percent of tax filers, according to the state’s finance department. And in the past decade, taxes collected from the most volatile form of income—capital gains—have doubled, making up a larger share of the state’s revenue and tying the state’s budget to particularly unstable economic cycles.

To address that, voters approved changes to the state’s rainy day fund in 2014. The changes serve as a check on spending, directing California to capture additional dollars in reserve when capital gains tax receipts are high.

Building reserves large enough for a state to ride through a recession is difficult, said Donald Boyd, a state finance expert at the University of Albany in New York.

“As a practical matter, it is very hard to build a rainy day fund that’s big enough to get you through a rainy season,” Boyd said. “You need huge amounts of money to offset the effects of even a modest recession.”

Be the first to comment