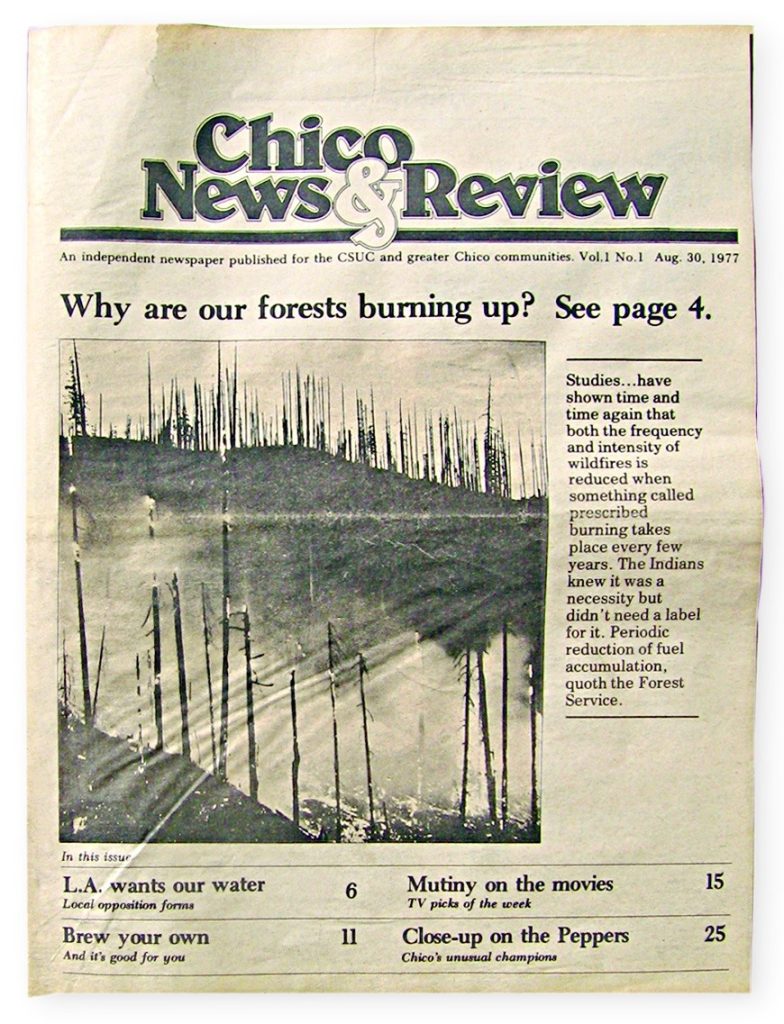

This newspaper has been in print since 1977, and if you have this issue in your hands, you are holding the final edition of the Chico News & Review.

As a 20-year veteran in the editorial department (and 33-year reader) of this paper, I am, like many of you, mourning the loss of such an important part of life in Chico, but as current editor-in-chief I’m also gearing up for the challenge of building a dynamic and engaged internet home for the CN&R. That’s my new job as the paper transitions to an online-only era.

As a news source in America that’s ceasing print publication, the CN&R is in good company. According to the latest report from Northwestern University’s Local News Initiative project, “Since 2005, the country has lost almost 2,900 newspapers.” Most of those casualties have been non-dailies like the CN&R. The closings are coming faster, too, more than 130 shuttered in 2023 and by the end of this year the U.S. will likely have lost a third of its newspapers in the past 20 years.

With the presses shutting down for this publication, Chico is left with just one print newspaper. Butte County won’t quite be a news desert—as more than half the counties in the U.S. are—but the absence of the CN&R and its critical alternative voice in racks around town leaves a huge local-news void.

So, what are are we going to do now?

The CN&R is making a commitment to online publication (something that’s often been an afterthought for most of the paper’s history) in an effort to reboot our community journalism.

For now that means, with very limited resources, that the CN&R will refocus on doing the job of keeping tabs on local government, connecting online to amplify conversations on the issues that impact this community. We will also continue to provide a comprehensive calendar of local events (our online calendar has always been even more exhaustive than our much-loved print version) and be the source for arts coverage in Butte County. We’ll keep Best of Chico going (voting will start in the spring), and we hope to be able to revisit some of the CN&R’s past signature promotions (CAMMIES? Some other musical showcase?).

With the absence of print, ad manager Ray Laager will explore new online advertising strategies, and we’ll depend on support from readers more than ever, most importantly we’ll need everyone to sign up for the free weekly CN&R newsletter and join us online.

Additionally, we are seeking likeminded folks for collaborative partnerships to improve local news and arts coverage, and will also connect with initiatives (e.g., Press Forward, American Journalism Project) dedicated to what many are calling a “local news renaissance” in this country.

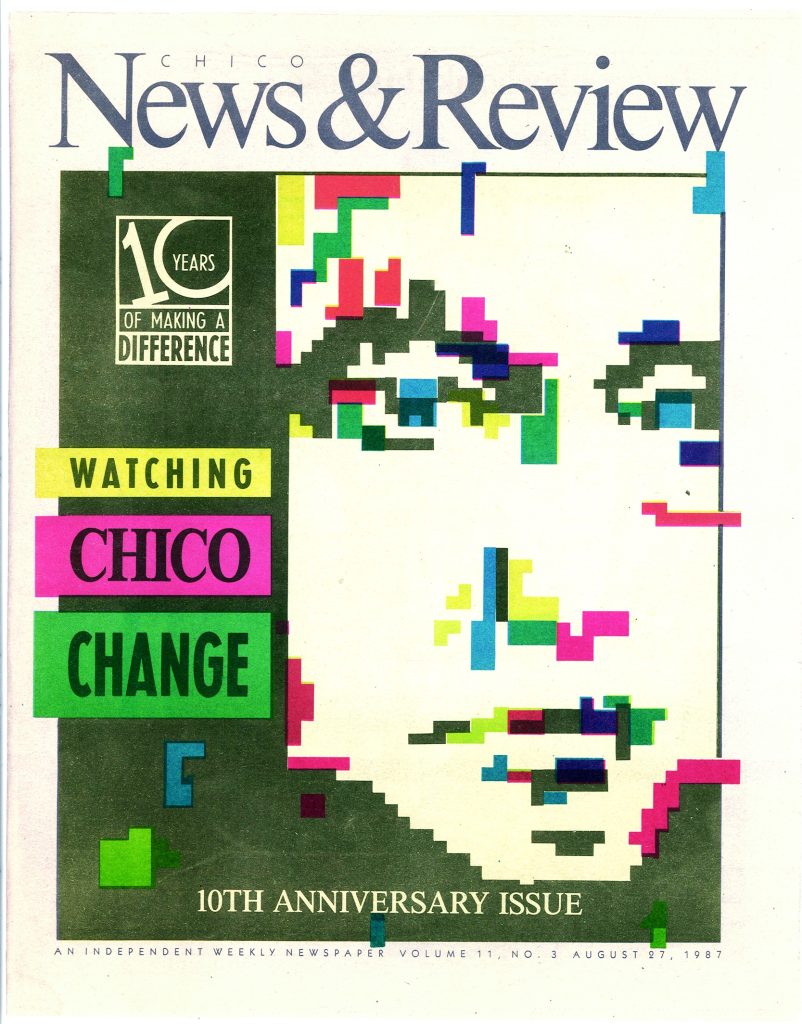

Since 1977

When the staff of the Wildcat student newspaper made the break from Chico State 46 years ago, it marked a new era for this little college town and this big rural county. Not only was the Chico News & Review born, but so too was liberalism in this area. The progressive streak that has run through the newspaper and this community has a direct line to the fiercely independent hippies and other rebels of those first few years who ran the paper as a collective as long as they could.

In the pages that follow, many of those kick-ass rebels and hippies—plus the gonzos, punks, bulldogs and other warriors of the fourth estate from throughout this paper’s history—share the stories that made good on the paper’s promise as well as their thoughts on what their work has meant to to this community.

There’s also plenty of grieving as folks say goodbye to the local institution that this publication has become while hoping that whatever comes next will have a similar positive impact on this community.

I’ve worked for this print publication for 20-plus years, more than half my days as an adult. As I read the submissions for this final print feature, many of the stories shared by multiple generations of the CN&R family mirrored my own history here. From Josh Indar’s reminiscence of our coverage of the ridiculous slate of candidates for the 2003 gubernatorial recall election, to the comforting picture painted by Howard Hardee of the rhythms of the big upstairs arts office in the old CN&R headquarters, which was my downtown home base for 17 years.

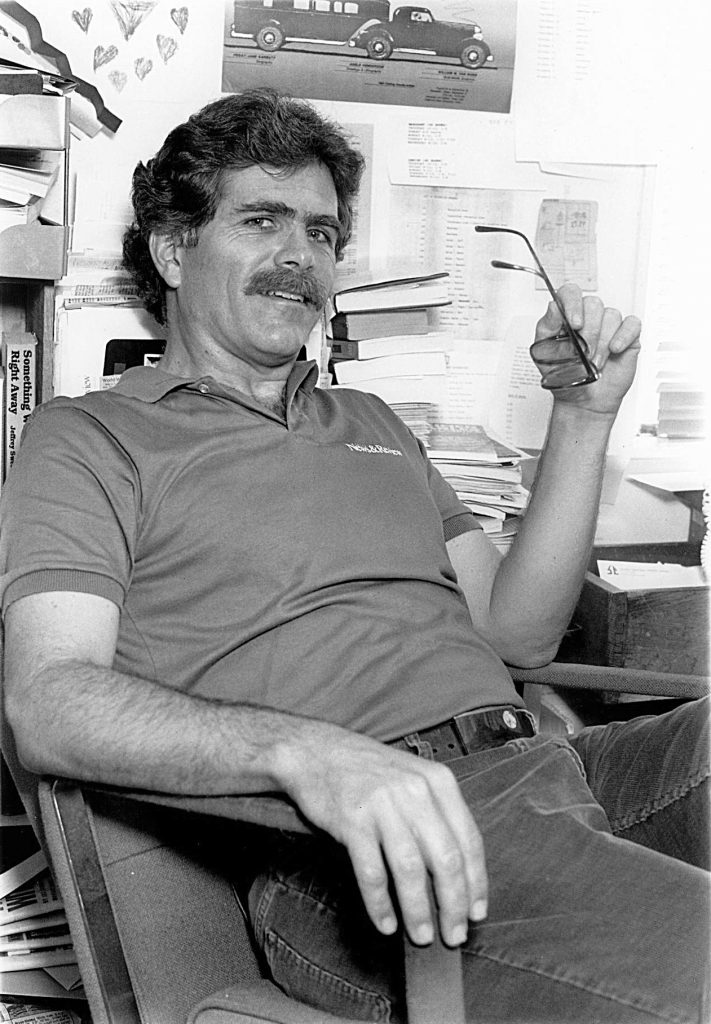

Jason Cassidy

Arts editor (2004-2006 & 2008-2020); calendar editor (2006-2008); interim editor (2020-2021); editor-in-chief (2021-2024)

I’ve said it in these pages before: Being hired by the CN&R changed my life. For most of my time here, my title has been Arts Editor, and the fact that this Redding hick wound up in that position in the middle of this fun, weird, always evolving arts-rich community was a miracle that far exceeded my teenage dreams. And I was damn lucky to get hired. When I applied in 2003, I was an English major who spent more time playing guitar and putting on rock shows than going to classes. I had taken one journalism course (at Butte College with CN&R Editor-in-Chief Tom Gascoyne, as luck would have it), and my work history to that point was almost exclusively spent in restaurant kitchens.

Tom gave me a shot, and I devoured the opportunity like a hungry dog fearful that the bowl might be taken away. With no other blueprint to follow, I molded the position to suit my vision of completely owning the art scene. Over time, that relationship with the community through the paper has became what defines me.

My first months on the CN&R job were a crash-course taught by an all-star team of local journalism legends—Tom, Senior Editor Bob Speer, Designer Tina Flynn, Associate Editor Devanie Angel, News Editor Josh Indar and photographer Tom Angel. Tom Gascoyne taught me courage and curiosity (prodding me to always try and open closed doors) and to appreciate the work we do (frequently pointing out how “cool” it was that our words were read by the community every week). I learned storytelling from Bob, copyediting from Devanie, and I (kind of) learned to stick to deadlines thanks to Tina, who has also been my longtime partner in, well, most everything the paper has done the last two decades.

So many different heartbeats have come through the offices to make this newspaper—and to party together—over the years.

We’ve rallied for all-hands-on-deck coverage of subjects silly and serious—from riding trikes in a downtown “bar olympics” to entering Paradise with heavy hearts after the Camp Fire to report on California’s deadliest wildfire. We’ve organized huge community events: the CAMMIES with myself and a succession of incredible sales mangers, Alec Binyon and Jamie DeGarmo; and multiple sold-out Keep Chico Weird talent shows at the El Rey Theatre with the superteam of DeGarmo/Melissa Daugherty/Meredith J. Cooper/Arts DEVO. And we’ve made lifelong friends with incredibly passionate, creative people who have gotten as much from the experience of working for as they’ve given to this community newspaper.

Josh Indar

Staff writer and news editor (2001-2006)

It’s a season for goodbyes and this is a big one. The CN&R has been not just a community institution for the 23 years I’ve lived here—it’s played the single biggest role in forging my identity as a Chicoan.

I started freelancing for the paper in 2001, and by 2002, I found myself serving as News Editor, churning out copy and raising all kinds of journalistic hell until my departure in 2006. It was a turbulent—some would even say scandalous—time for the paper and a difficult time for me personally, as I’d just arrived in town, a new father and full-time student who didn’t know a single person here and didn’t plan to stay long. But Chico has a way of keeping people around. As former CN&R Editor Tom Gascoyne told me at the time, “Chico is like a big easy chair—get too comfortable and you won’t be able to get up again.”

Like so many who move here “temporarily,” I got plenty comfy, and the CN&R played a big part in that.

For newbies and townies alike, this paper has long served as a gateway to community and a road map to the oft-obscured cultural and political landscape that makes us who we are. As a reporter, I was lucky enough to have a front row seat. And man, what a show it was. Thinking back on my short tenure at the paper, it seems almost unbelievable how much the tiny staff of this little weekly told us about who we are as a region and who was pulling the strings.

In those days, Chico was struggling with its identity, trying to forge a future for itself as something more than just a party town or a destination for latter-day hippies looking to drop out of society. That struggle for identity was mirrored inside the pressure cooker of the CN&R newsroom, where strong opinions and murky horizons led us into passionate and sometimes vociferous discussions on how to best serve our readers.

Journalism was changing and we had to figure out how to change with it. Ad revenue was shrinking, competition was fierce and the internet was drawing eyeballs away like sirens to a rocky shore. We knew that to survive we had to have better writing and juicier scoops than the daily paper, arts coverage and commentary as edgy and hip as the other weeklies in town, and somehow still maintain journalistic standards. We had to be everything to everybody.

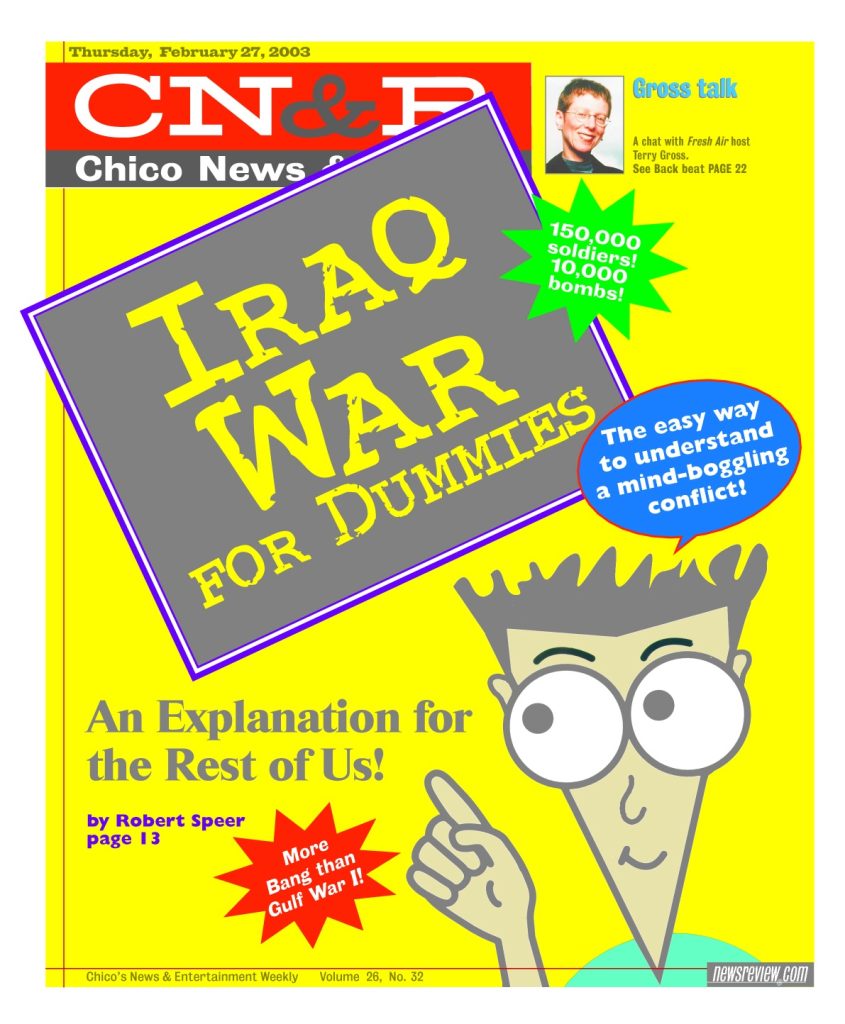

It was an impossible task, but what I love about that time is how hard we all worked to make it happen. I guess when you don’t know something’s impossible, you have no reason not to try. And we tried everything. During the 2003 recall election, we were the only paper who attempted to interview every single one of the 135 weird and wacky candidates running for governor—a nonsensical endeavor that nonetheless turned out to be hugely entertaining and historic. Running a paper this way was an insane approach that got us into all kinds of trouble, but it paid off with some of the very best journalism this area’s ever seen, and that’s not just my opinion. In 2004, the California Newspaper Publisher’s Association named us the best weekly in the state, no small feat for a shoestring operation in a backwater like ours.

The freedom to try anything and everything was exhilarating for a writer like me, who’d felt stifled by the format and time constraints of my previous gig at a metro daily. But at the CN&R, the editors greenlit everything I pitched them—it was madness! I carried a gun around for a story on concealed weapons permits; flew to Concord in a B-17 bomber; had my phone tapped after interviewing a Red Bluff airplane mechanic who was deported for purported links to 9-11; and got our building buzzed by a black helicopter owned by some alleged mobsters working a shady land deal. I haunted every corner of the upper valley, writing about wild horses outside Susanville; a Nestle water grab up in McCloud; and the massive turbines beneath Oroville Dam. I covered grisly murders, shocking assaults, killer cops, cops getting killed, the war on Halloween, and the endless machinations of developers and politicians who, as it has always been, have their own ideas about how our region ought to be run.

Who will tell those stories now? And if they do, how will readers find them? How can a group of folks bound together by nothing more than geography form a common identity when there is no common conversation, no agreement on what is happening or what is important? The loss of the printed CN&R is part of an ominous trend playing out across the country, where local journalism is dying due to public apathy and the relentless pursuit of profits over community. Same as always. Some say the internet is just as good or better than old-fashioned newsprint, that it empowers the little guy and allows us to form communities with like-minded folks.

Wouldn’t that be nice.

To me, the internet looks like an overflowing septic tank of misinformation, a divisive and corrosive medium that brings out the worst in people and blinds us to our common purpose and humanity.

Still, I hope the CN&R is successful online. We desperately need it to be, because the stories we tell ourselves become who we are, and a community that can’t tell its own story is already lost. To whomever attempts to bring this old rag kicking and screaming into the modern age, I hope you will find the courage and energy to tell every story out there just as you see it. And I hope you’ll find an audience as loyal and generous as CN&R readers have always been. Try anything and everything, raise some journalistic hell! Strange as it may seem, it’s the impossible tasks that need doing most.

Jeff vonKaenel

News & Review president/CEO (1980-2024)

I will never forget my first week at the Chico News & Review. I arrived in Chico in June 1980. The situation at the paper was somewhat dire. Payroll was behind three months. The paper owed printers up and down the state, and the IRS had set up a payment schedule for nonpayment. Butte County’s average household income was near rock bottom. Chico college students, Oroville blue-collar workers and Paradise retired senior citizens were not rolling in dough. And because it was June, the students were gone and advertising would be nonexistent until August.

Nevertheless, I was optimistic: On my first day at work I sold a full-page ad to a judicial candidate who was running in the June primary. But the real reason for my optimism was that even though the staff had not been paid for three months, they were still showing up for work, putting out a great newspaper. They were a group of dedicated people I wanted to hang out with.

And then there was Chico.

Chico is a special, special place. I had come from Santa Barbara, where I spent 10 years, first as a college student and then working for an alternative newspaper, the Santa Barbara News & Review.

Everyone told me, “You will be so happy here.” And they were so right, both my wife Deborah Redmond (who started at the paper in 1981 and has kept the machine of the paper on track as the long-time “director of nuts and bolts”) and I fell in love with this area. The college. Bidwell Park. But most of all, the community spirit.

I missed the first three years of the paper’s history—when the college paper, the Wildcat, left campus and turned into the CN&R—but I have been around for all the ups and downs during the 43 years that followed.

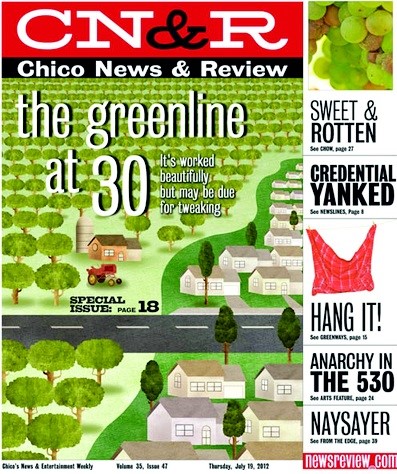

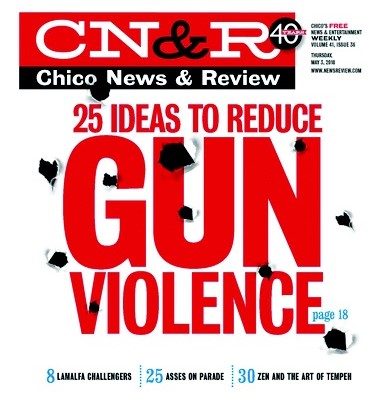

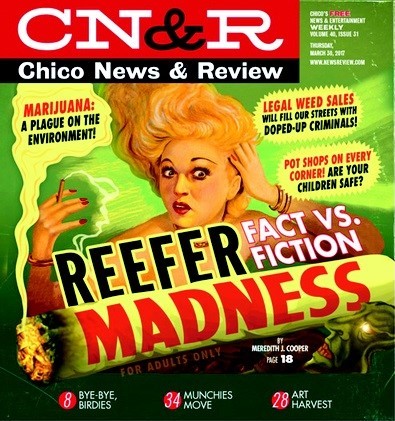

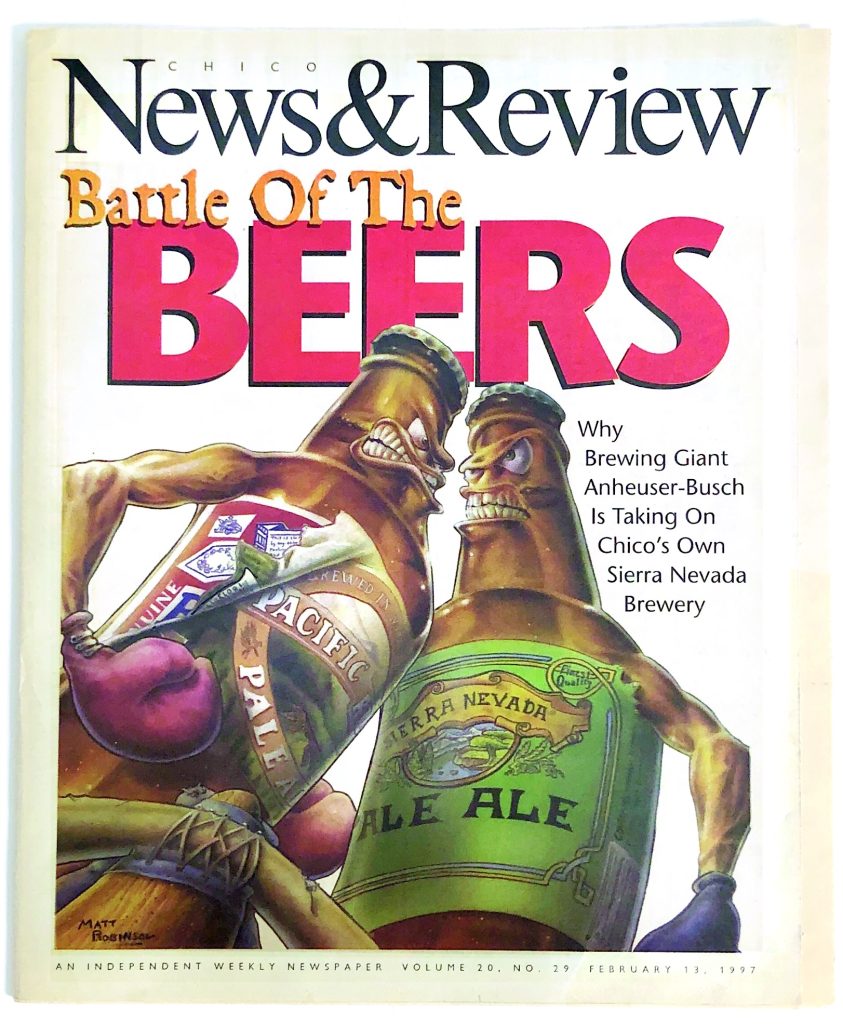

If you are holding the printed copy of this last issue, please know that what makes it so special is the other 85 million copies that preceded it. In these pages, we documented the creation of the Greenline, the numerous ebbs and flows of liberal and conservative city and county governments, the creation of a robust arts community, the birth of the Sierra Nevada Brewing Company and the Camp Fire and its aftermath.

It was in these pages that Republicans, Democrats, Independents and the “we don’t give a damn” heard their own voices. Even more importantly, they heard each other.

One of the most unusual and satisfying friendships I developed over the years at the paper was with very conservative County Supervisor and State Assemblyman Bernie Richter. He was so opposed to our paper that he funded a conservative weekly to try to put us out of business. Yet eventually, through deep and prolonged conversation, I convinced him (via his Ray’s Liquor store) to cater the CN&R’s 10-year anniversary party. I visited him at Enloe Hospital when he had back problems. He came by Enloe to visit me and my wife Deborah after the birth of our son. I spoke with him a few weeks before his death in 1999.

It has been an incredible 43 years. There are too many people to thank and not enough space to thank them.

The paper owes a huge debt to Tina Flynn, the longtime designer who was there near the beginning and is still at the CN&R (wearing many hats as always). Thanks are due to the many ad managers including Alec Binyon and Jamie McCormack, and the many members of the sales staff including Brian Corbit, who made sure the paper survived year after year.

We owe a debt to the distribution team who showed up every Thursday to distribute those 85 million copies. Also, the business department staff who paid all the bills, especially Charles Marcks, our business manager for many years. And the many talented designers who made the stories and ads look so beautiful, including Flynn and fellow longtime art director Don Button.

Thanks to the reporters who got to know our community and brought you so many stories. And the editors: Bob Speer, who helped start the paper and came back numerous times to save it; my Santa Barbara college roommate George Thurlow, who brought us national recognition; and Melissa Daugherty, who oversaw our 300 Camp Fire stories as we helped our community recover and grieve.

Thanks to Evan Tuchinsky for not only his service as editor, but for his frequent returns to help the CN&R during its times of need.

And now, we are so grateful to Jason Cassidy, who has covered the arts for 20 years and now will be overseeing the transformation to an online-only edition along with Advertising Manager Ray Laager.

As we close one door with the last print edition, we open a new door with an enhanced online version of the CN&R. While much has changed since the paper was born in 1977, what has not changed is the need for an independent voice that covers the greater Chico community, including Oroville and Paradise. We continue to need a platform that allows many voices to be heard, even when they are yelling at each other, and is not afraid to cover controversial issues.

Over the years, we have made mistakes. At times we have contributed to the polarization in our community. For this I am sorry. But whatever disagreements you have with the CN&R, and I have some of my own, I would ask that these be balanced with the recognition of the importance of our Camp Fire stories, our arts coverage and our Best of Chico contests. We don’t expect or even want you to agree with us all the time. In these divided times, I believe the Chico News & Review is even more important in 2024 than it was in 1977.

As we transition to a digital-only platform, part of our online presence will include spotlights on local businesses to help ensure that Chico residents can still find and support their local business community. To stay connected, please subscribe to our free weekly editorial newsletter. And please consider donating monthly to support our journalism. Your support is a commitment to keeping our community informed, engaged, and thriving.

Looking forward to 2024, I am once again optimistic about the future of the CN&R. Why? It’s the faith that I have in the people and businesses of Chico and Butte County. Thank you for continuing to support local independent journalism.

Steve Metzger (aka Henri Bourride)

Contributor (1980-2023)

Though I’d sold a handful of freelance magazine articles by 1980, my first actual professional writing assignment came from the offices of the Chico News & Review late that summer. Well, not “offices” per se. Actually, well … a bar. Probably the Towne Lounge. Maybe Canal Street. I forget.

The formidable CARD men’s softball team the Pests—made up of Chico State professors and grad students and local journalists—were sharing pitchers of beer one evening after a game (probably a loss) when left fielder and then CN&R editor Gary Fowler asked me if I’d be interested in writing a piece on Chico fashion for Goin’ Chico, their huge annual special issue that was mailed to new students and filled the racks around town for weeks.

“Fashion?” I said. “Moi?”

He filled my mug. “Go for it, man. Do whatever you want. Funny. Serious. Doesn’t matter.”

I took a long pull and shrugged.

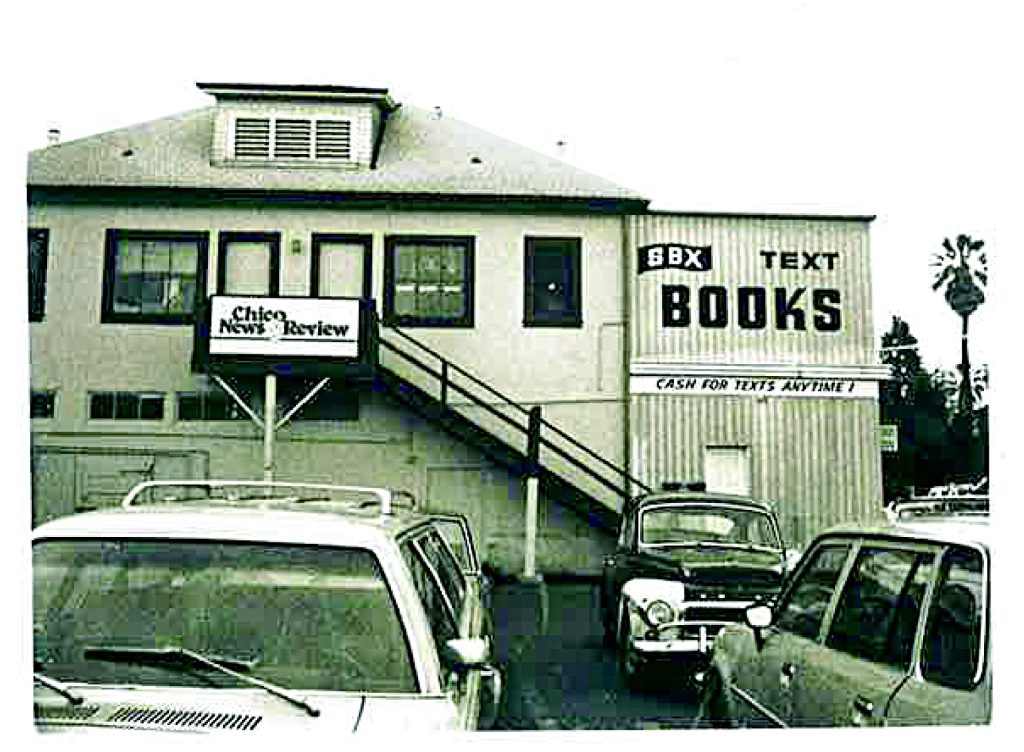

I ended up writing a tongue-in-cheek piece about the importance of fashion to academic success and gave it to Fowler. When I didn’t hear back, I nervously stopped by their (real) offices, located upstairs from what is now the Naked Lounge. The editors were in the middle of laying it out and were gathered around the proofs, howling. They got the joke.

Thus was born a 43-year relationship with the News & Review, which I’ve cherished almost as much as I have the paper itself.

Over the years, I’ve written many cover stories (including one on author John Gardner, who taught creative writing at Chico State in the early 1960s, and one on climbing/skiing Mt. Shasta), tons of reviews (of CDs, books, movies, Laxson Auditorium shows), and lots of guest editorials. Plus more spoofs, including one about JFK Jr. after he died. I’d grown weary of all the articles by writers who claimed to have known him so I wrote a piece about how we’d grown close when he was a student in my freshman writing class at Chico State. Every sentence was a joke (he was the sole occupant of the top floor of one of the dorms; he loved skiing Mt. Lassen because his family owned it; we hung out at La Salles a lot because he couldn’t pass the bar …), but not everyone got it. Lots of folks expressed their sympathies, and a few local teachers asked me to come speak to their classes about him.

One day in the spring of 2003, I came across an ad in the paper that said they were looking for a food writer. Anyone interested should submit a couple of sample columns. I’d spent the previous 15 years writing travel books so had written about food a lot—both in the form of restaurant reviews and recipes from places I’d researched. Since I firmly believe that reviewers—especially restaurant critics—should remain anonymous, I invented a character who would be the “author” of the reviews. He was a good ol’ boy, fond of barbecue, grits, cheap American beer, and tailgate parties. I sent two to then editor Bob Speer. He got back to me shortly. “Steve, these are funny and well-written, but I don’t think that voice would last very long. Why don’t you try something else?”

I was bummed, but went back to the drawing board and invented a totally different “author,” one Henri Bourride, a 50-pound-overweight French-chef wanna-be who had recently moved to Chico from New York City. Henri was fond of bouillabaisse, polenta, cabernets, and sidewalk bistros. He was a lovable goofball, often wrong, and talked about himself in the third person. His assistant was Miss Marilyn, his aging French poodle. He was clearly gay.

Speer liked Henri and said that he thought the voice would last a lot longer. “Can you do one every other week?” he asked. Thus was born a 12-year series of “Chow” columns. I wrote something like 250 of them.

So I was among the many, many Chicoans hugely saddened by the news that the paper had fallen victim to COVID in 2020, though I was thrilled when Jason Cassidy and the tiny new crew rallied from their tiny new office and managed to continue with regular online editions and a monthly print edition. I kept contributing, not only financially but with long online essays and articles.

And now I’m even more saddened to learn that this is the final print edition. I’m thinking about how much the paper’s meant to my writing career over the years, and about how it’s shaped my Chico experience—the always-thoughtful election analysis, the gutsy investigative pieces on local politics.

But I’m also thinking of all the amazing people who have helped make the paper such a bright beacon in often-dark times—some of whom I’ve been lucky enough to cross paths with and whose work I’m humbled to have been included with in these pages: Fowler, Speer, Cassidy, K. Patrick Conner, Juan-Carlos Selznick, Joe Kane, Larry Tripp, Anthony Peyton Porter, Tom Gascoyne, Bryce Conrad, George Thurlow, Kim Weir, Evan Tuchinsky, Melissa Daugherty, Kevin Jeys, Ken Smith, Mark McKinnon, Tina Flynn, Mark Thalman, Tom Angel, Josh Indar, Joe Martin, Danielle Toussaint, Carey Wilson. Giants all. Thank you.

Melissa Daugherty

Special projects editor, news editor and managing editor (2007-2013); editor-in-chief (2013-2020); editor-at-large (2020-2024)

I was interviewed by the TV news when I became the CN&R’s editor-in-chief. In addition to simply covering the changing of the guard—me succeeding Robert Speer—the reporter asked what it meant to be the first woman to lead the paper.

It didn’t dawn on me then that I also was the first one to lead any professional newspaper in Chico.

I told the reporter I didn’t see my promotion as particularly groundbreaking. After all, this was 2013.

How naive.

I realized it was a big deal for Butte County when I got a death threat early into my tenure. It was scribbled on an editorial I’d written regarding a police shooting I viewed as unjustified, an opinion validated a few years later when the city of Chico settled a wrongful death lawsuit with a nearly million-dollar payout.

At the time, I asked Speer how many death threats he’d received in his 40 years of journalism. The answer: none. I was shocked, but shouldn’t have been.

The threat was telling. The writer called me a slut and a whore, among other things not fit for print. It was the first of several such notes. That’s on top of the woman-hating voicemails and emails—too many to count.

But for every vile message from an incel or male supremacist, I received hundreds of others from supportive readers, men and women.

At first, it changed me a little. Instead of shrinking, I swung harder. Too hard on occasion, I’ll admit.

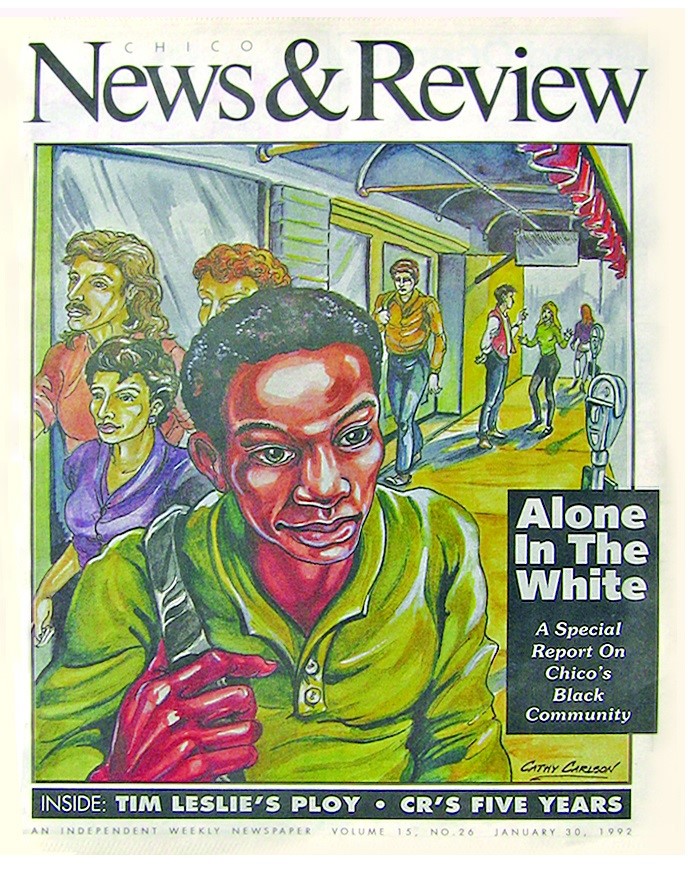

In truth, it took me years to find my footing as editor. But when I did, I was more excited than ever about journalism in Chico. Over the years, I assembled the best team of journalists, reporters who left other outlets to be challenged by this paper’s higher standards, the type of reporting that makes a difference, bringing awareness to issues that ordinarily wouldn’t reach the public consciousness, and in many cases actually affecting change.

There are too many examples to list, but the one closest to my heart is the Chico Police Department making it policy to announce when a deceased person is found in a public right of way, something a former police chief agreed to do solely at my unrelenting urging. You know, because homeless people are human beings and the public needs to discuss what it means about society, our community, when so many are dying on the streets.

Sadly, no other organization has been able to step in to do the type of enterprise and investigative work that was the hallmark of this newspaper, leaving a gaping hole in the journalism landscape. The CN&R has been the pulse of Chico, and watching it flatline hurts.

One of the hardest things for me to accept since the pandemic shutdown is that the paper was decimated just months before we were set to expand our newsroom with the addition of a grant-funded reporter. I suppose it’s a little selfish on my part, but watching my vision for its future slip from my grasp was devastating.

And now, having spent more than a third of my life working for this publication, saying farewell feels a bit like grieving the death of a loved one.

I’m in good company. Longtime Art Director Tina Flynn recently told me she felt like she was going through the stages of grief herself. More than half her life has been spent in service to the community through the CN&R.

“Service to the community” are the key words. Anyone who’s worked for the paper knows it’s more about giving than receiving.

By the time this last print issue hits the racks, I may finally have reached “acceptance.”

I think I’m close, because I know that, despite the sadness I now feel, I’d do it all over again.

Kevin Jeys

Early staff writer (1979-1981) and longtime contributor

When Gary Fowler was CN&R editor his father was running McClelland Air Conditioning. Which, naturally, was intimate with area developers. His dad knew all those people; so did Gary. People we were ceaselessly skewering in the newspaper. Like Dallas Lewis, a man we commonly monikered Malice Sue-Us, pretty much begging him to come after us for our Libels. After nearly every issue one or more of these people would call Gary’s father and exasperate: “Jim! Something needs to be done with that boy!” But that never happened. Gary would not be done. He just kept on keeping on. That’s the sort of people who worked there. I raise a glass to all of them.

When the town burned down then-editor Melissa Daugherty, who I had never met, drove up here, though the town was closed, to basically take care of me. She hadn’t known me, but I had been at the paper, and so was of her karass. That’s who we are, too, CN&R people. We will always be connected. And. For all time.

Mark Lore

Associate editor, calendar editor, arts editor (2004-2008); contributor (2008-2020)

In the mid-’80s my family would go to the cultural hub that is Round Table Pizza in Red Bluff on a Friday night, where I’d grab a Chico News & Review from the stand. At that point I don’t think I even knew where Chico was. But reading the columns and seeing those ads for the music venues, I knew I should probably be there.

By the early ’90s I was driving to Chico to see shows (Mudhoney and Monoshock at Lava Lounge!), and finally moved to town in 1996, while also realizing my dream of writing for … The Synthesis. Anyway, the CN&R was still huge for finding the good shows, and knowing where the cheap drinks could be drank. And I could tell it was the better paper, with a far deeper connection to the community.

Once I awakened from my new-to-Chico hangover, I began the path I was meant to take (thank you, Peter Berkow)—studying journalism at Chico State, and with that came an internship at the CN&R. I filed a few stories that summer, and met some of the motley crew I’d eventually call colleagues and lifelong friends.

My official tenure at the CN&R was comparatively short to the many that came before and after. I’d like to think I left some sort of a mark (scar?) in that time. But the paper has definitely helped shape me. The skill of being a writer and editor, and the desire to fight injustice have always been in me—the CN&R helped me hone those things and put them to important use.

I’ll always be a journalist, even as the institution continues to deteriorate. My hope is that the CN&R will find new, creative ways to exist online. The alternative is not a good one, as checks and balances for city governments are more important than ever. And shedding light on local artists and musicians is essential.

Here’s hoping the CN&R’s almost-50-year legacy will at the very least inspire people to continue fighting the good fight. And give voice to those who can’t.

George Thurlow

Editor-in-chief (1981-1991)

I came to Chico in late 1981 as the Editor of the Chico News & Review at the invitation of Jeff von Kaenel, a dorm mate at UCSB who introduced me to journalism in Santa Barbara.

I had just returned from covering the war in El Salvador and it was quite a change to walk into La Salles at 5 p.m.

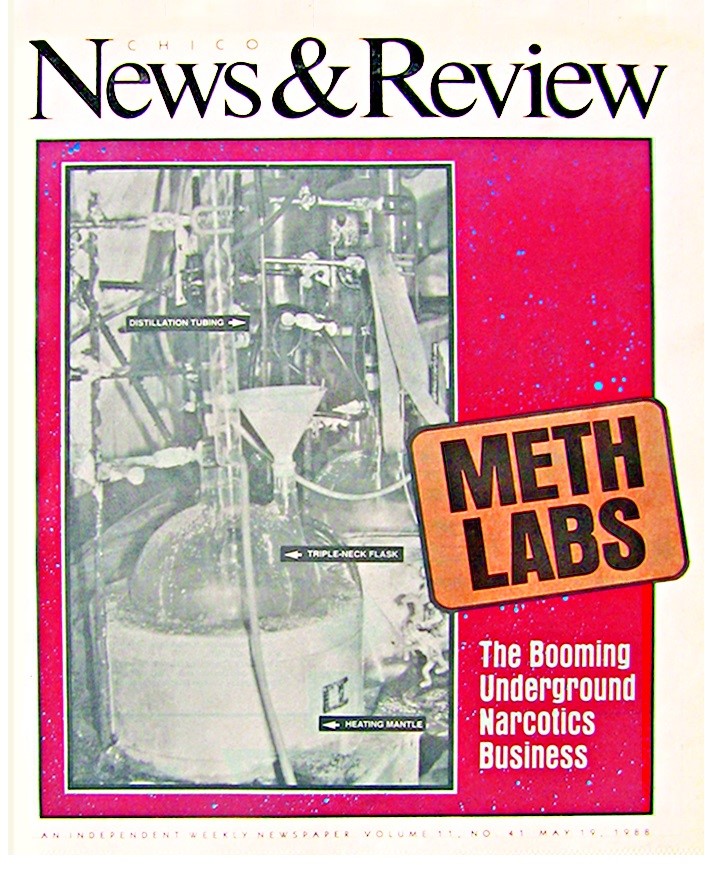

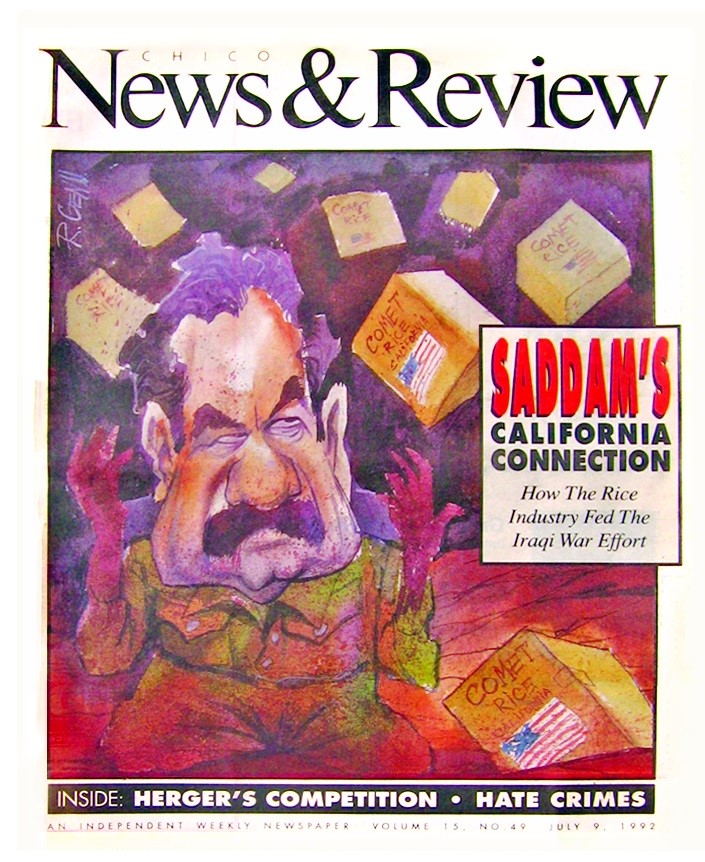

I developed some exciting stories, starting soon after my arrival with a series of pieces about how wealthy rice growers were cheating the federal government in the rice subsidy program.

Then it was on to a series of revealing stories showing then Sen. Jim Nielsen, who bragged he was a farmer, was in reality a pesticide salesman who fudged on his legal residence and enjoyed free cowboy boots from special interest groups.

I studied the underbelly of the huge cocaine business in Chico in the ’80s, showing how restaurants, lawyers and banks set up money laundering schemes. After my first story a N&R staff member visited me in tears telling me the bad guys had a simple message for me: my son attended Little Chico Creek Elementary School. I was not a brave soul then. I dropped the ongoing story. I would rather have my son than reveal the names of accountants, lawyers and bankers who were involved in the money wash.

We had a tremendous staff with Danielle Toussaint and Mark Thalman covering the environment and Butte County’s rich natural world; Robert Speer promoting the arts and theater (he was the best copy editor I’ve ever met); Tom Johnson producing a war story like no other before. Others came and went to remarkable careers: K. Patrick Conner to edit at the San Francisco Chronicle; Mark Ulriksen to illustrate covers for the New Yorker; Kim Weir to Moon Publications.

We covered politics and government with a fierce attitude. We celebrated the best of Chico and its people.

Jeff vonKaenel provided the spark and his wife Deborah Redmond, also a Santa Barbara News & Review veteran, held it all together. Tina Flynn was upstairs keeping an eye on everything.

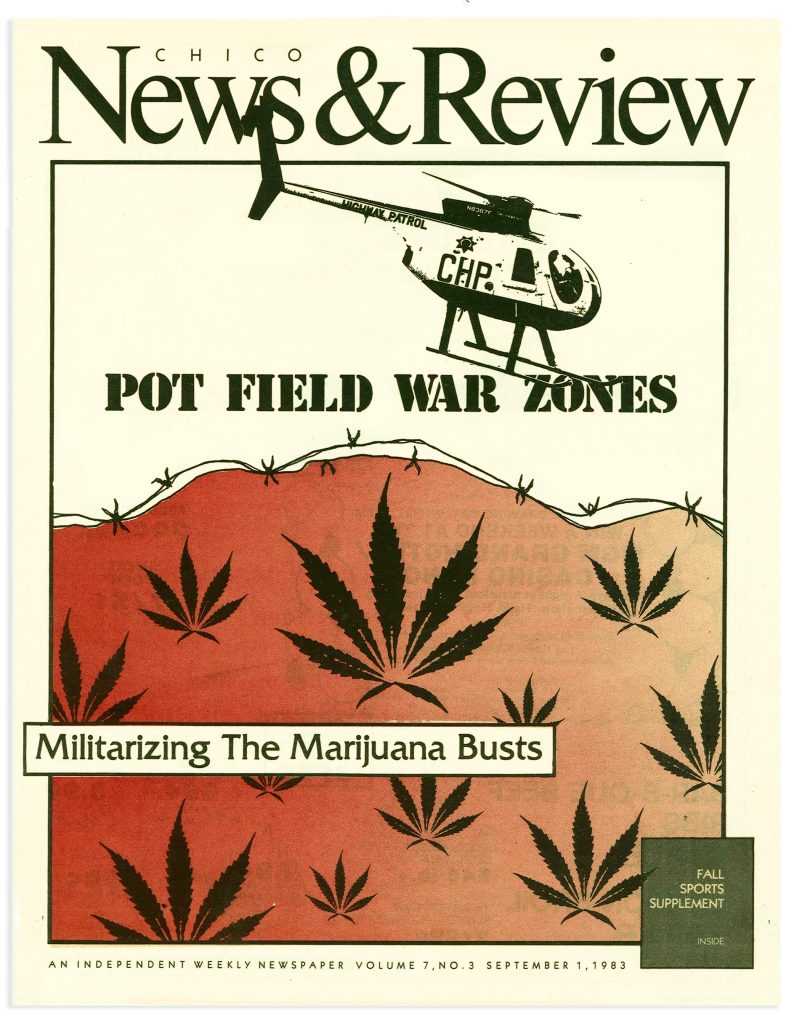

I met my wife in Chico and her daughter. My two sons were born there. We owned property in Butte Creek Canyon but when I learned somebody was growing pot on an almost unreachable cliff, I decided to sell it. Like so much of Chico, it had beautiful views and a peacefulness not found anywhere else. But it was in the middle of the pot wars of the ’80s and the DA said he would confiscate property where marijuana was found, whether the owner was aware or not. That was the dialectic of our Chico,

I have come full circle with this article having returned to Santa Barbara. My book on El Salvador. Blood On All Our Hands, will be released in February 2024 and it is being laid out and published in Chico by veteran word craftsmen Dave Hurst and Heidelberg Graphics’ Larry Jackson. I could have taken it anywhere in the world, but I trust the work of these Chicoans. They are the gifted guardians of the printed word. They will continue the legacy of the Chico News & Review.

Tina Flynn

Art director, production designer, wrangler of cats (1978-2024)

My job has mostly been behind the scenes producing the print version of CN&R but I’ve been fortunate to be around journalists all the time. That taught me these simple life lessons: be curious; always tell the truth; be aware there are more details below the surface; have a plan B; respect a deadline.

Ashiah Bird (née Scharaga)

Staff writer (2018-2023)

My history with the Chico News & Review is permanently etched onto my skin.

In late 2020, I got two small quote marks tattooed on my wrists. When I told my tattoo artist about the style I wanted, I said “like this” and showed him a picture of a story in the CN&R. These tattoos complement another one of mine, my first, that I got during my first year as a writer with our paper: an intricately designed pen nib with a sword in the center on my right inner forearm.

In many ways, I am still grieving the loss of my life as a full-time community journalist and CN&R staff writer. After my colleagues and I were laid off in March 2020 due to the pandemic, I became a freelance writer for our then online-only paper. Shortly after, I was rehired part-time, and I stayed in that role as long as I could. I reached my fifth anniversary with the paper in January, and my last byline was published in our August 2023 issue.

It’s difficult to encapsulate those years and what they meant to me. My experience at the CN&R has forever changed me for the better. I became a better journalist. A better truth seeker. A better story teller. I became deeply connected to my community. And I made friends that I now consider family.

CN&R Editor Jason Cassidy beautifully officiated my wedding, and my husband and I have played music together in his backyard. I am a proud nanny of our Art Director Tina Flynn’s precious senior cat. And Melissa Daugherty, CN&R editor-at-large, and I grew so close over our shared love of community journalism and thrifting that we now affectionately call one another sisters.

My work at the CN&R also helped land me my current job with True North Housing Alliance, the nonprofit that operates the Torres Community Shelter, because of the relationships I established as a reporter covering issues related to homelessness. I also dove headfirst into reporting on the recovery of survivors after the Camp Fire, documenting their struggles and stories, advocating for them in the only way I knew how: through my printed words on a page in our local newspaper.

In all of the work that I did, I always strove to represent the humanity and dignity of folks, especially those who are so often demonized, marginalized, victimized and silenced. To those interviewees, all I have is gratitude for you—for your vulnerability, for trusting me with your story, your truth. I’ve forever been changed by you. I’ve forever been changed by my time at the CN&R.

And now I carry a permanent reminder of that everywhere I go.

Ken Smith

Staff writer/contributor (2009-2024)

I moved to Chico from San Diego in 2009 and, at the time, I wasn’t too stoked about it. Having grown up in Redding, I’d spent half my life trying to escape Northern California, and was quite fond of the life I’d built over a decade in America’s Finest City.

As I prepared for the move, a good friend and fellow journalist who’d spent a few years here gave me one of the best and most fateful pieces of advice I’ve ever received: “Hit up Jason Cassidy, the arts editor at the Chico News & Review. He’s the best dude, you guys like the same weird stuff, and he’ll give you work.” I took his advice.

There is no better way to become intimately familiar with a place than to work at a newspaper, especially one with the history, independent spirit, and commitment to community as the CN&R. Freelancing for the paper, I quickly became entrenched in the local arts scene and branched out to write the occasional news story and contribute features to the now long-defunct Greenways and Healthlines sections. People invited me into their homes to share their life stories, and I fell in love with a town that—fortunately—was a far cry and safe-distance away from my hometown.

I remember my first visit to the office, when Jason invited all the arts freelancers in one Friday afternoon for shots of whiskey with some of the staff. I was able to put faces to the names I only knew from the staff box, though they were honestly hazy from the drink by the time I left the building. I remember then-editor Bob Speer asking one of our ad people about his recent excursion to Burning Man, and he responded that his favorite part of the trip (tee hee) was a day spent exploring the art installments after consuming a heroic dose of magic mushrooms. These were professional dudes who wore ties to the office and whose work I respected. I knew I’d found my people.

In early 2012, I was asked to write my first cover story, and given carte blanche regarding the topic and writing style. I opted for a series of vignettes about my relationship with my brother Craig, a magical dude who had schizoaffective disorder. The week it was published, Bob called me into his office and offered me a staff writing position. I accepted, and for the next few years I had the best job in Chico, writing into every section of the paper and becoming even more ingrained in the community.

The story about my brother went on to win top writing honors from the California News Publishers Association that year, my first of several awards from them, and I contributed to the newspaper as a whole winning many more. I don’t mention this to brag, but to illustrate my gratitude. Print and independent journalism were already in their death throes then, and writing jobs were (and remain) increasingly scarce. It was even more rare to find an outlet that gave me as much freedom and editorial input as I’ve been blessed with here.

One of my early assignments as a staff writer was an exit/entrance piece that required me to interview my outgoing and incoming editors—Speer and Melissa Daugherty, respectively (talk about pressure). I asked Bob, one of the paper’s founders from the rebellious Wildcat days, why he’d chosen to stay in Chico and maintain a relationship with the CN&R all these years. “Because I found a community worth fighting for,” he answered, words that continue to resonate with me.

I stepped away from my staff position in early 2018, though I continued to contribute to the paper regularly. When the Camp Fire hit, I reached out to Melissa to offer my pen and within hours I was at a makeshift emergency evacuation center at Chico’s Neighborhood Church. Two days later, I made my first of many trips into the still-smoldering burn scar. In addition to reporting, we took pet food and water for the four-legged survivors, and lists of addresses so that, at the end of the day, we could tell friends and fellow staffers if their houses still stood.

I also spent days in the evacuated zone below Oroville Dam as the threat of “catastrophic failure” loomed. I rejoined the staff to help keep the paper alive after COVID hit, in time to cover the tragic North Complex Fire, local protests in the wake of George Floyd’s killing and the continuous plight of Chico’s unhoused.

Again I mention these things in appreciation and not hubris: I am thankful for the opportunity to serve my community the best way I know how—through my witness and with my words. And I’m grateful for the CN&R’s 46 years of helping to keep Chico “a community worth fighting for.”

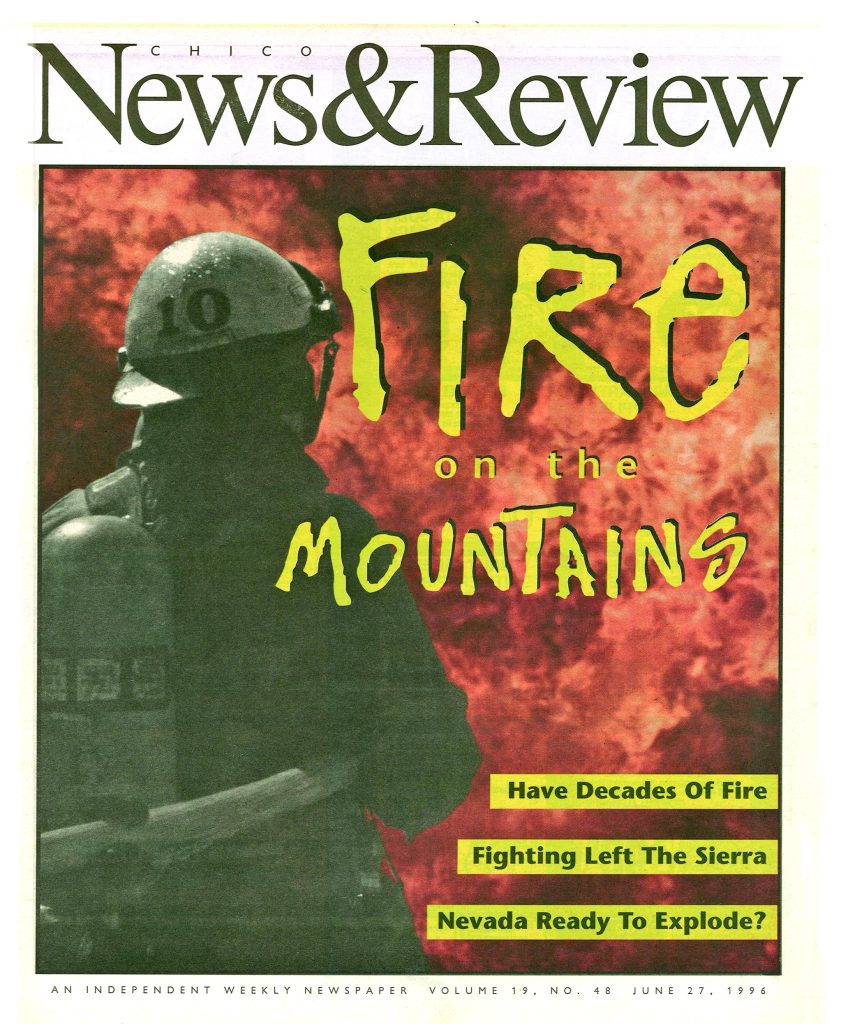

I’m also worried about that same community. Fires will burn again. The local impacts of homelessness, poverty, policing problems and inequity aren’t disappearing. As the pandemic and its fallout proved, situations we can barely imagine will continue to manifest. Chico is not the same one-of-a-kind place I moved to and fell in love with more than a decade ago, and there are forces who would be happy to see many of the aspects that make it unique disappear. Politics—local and otherwise—get crazier by the day, and democracy itself is in peril. I know the CN&R will continue the good fight online, but not having the power of print Is a great loss.

My tenure at the CN&R also ends with this final print issue. I’m proud of the work I’ve done and to be one of the last standing, alongside Jason, who started my journey here and has worked exhaustively to sustain it. And I’m glad, more than I can ever express, that I took that friend’s advice and reached out to him.

Elizabeth Kieszkowski (aka Bitter Betty)

Arts editor (1989-1996)

Chico had something really special going on in the ’80s—and some of the best of it probably happened before I moved to town in 1988. It was a vital time in Chico, with art galleries, book and record stores, bars and stages, and miles of canyonland to inspire sunbaked thoughts, along with raw, independent music pushing up in unglamorous places, as long as there were young, creative and/or questing people around. Colleges created a nexus for different kinds of scenes, and Chico State fed the town; it helped to have an art school, and places people could get together and start a party-sized creative riot. The music scene was hot, with good bands in town and great bands coming through town. It was a special time, with one-of-a-kind, talented people, and we made something at the Chico News & Review.

We’ll debate the internet another time, but the fact that digging up news about what was happening required either talking directly to someone or physically being somewhere—a library even—made everything that much more challenging/scary/rewarding. I’d discovered the magic of reviewing art and music with the UC Davis college paper before I came to Chico. (You mean I could just ask to talk to The Flaming Lips and they would call me from an Arizona phone booth, two or three band members crowded in, raving about Evel Knievel?! And then I could go to the show, for free!?) So I figured I really didn’t need money (I was wrong, but I was young), and I decided to write for a “living.” When the Chico News & Review hired me for, I think, $9.50 an hour, 30 hours-a-week in the first year, I thought I hit the big time—and in a way, I did.

For some other people it’s 4-H or team sports, or that gang they fell in with during high school, but the way I see things is shaped mostly by the written word, friend to misfits everywhere, and rock ’n’ roll, because music is a way to break free. And in Chico circa 1989, those things became intrinsic to my (sort-of) adult life—I was a writer, and as the CN&R’s arts editor, I wrote about music, mostly, and things I came to care about because of music, like art and artists, sexuality, post-punk sad-balladeers Vomit Launch and ’50s gateway drug Matt Hogan.

The beauty of working for the CN&R was we were creating, and we were informing. We aspired to be worth readers’ time, and accurate, even with the crazy stuff (h/t firestarter Kevin Jeys)—but editor Bob Speer let us take it as far as we could, and sometimes farther. He worried that I might be harassed when I wrote about imagining myself as a man (in hindsight, Patti Smith?) to imagine doing what I wanted to do, but I don’t think he knew I was already getting fan mail in the form of penis Polaroids (no internet, remember) and letters from jail. As Bitter Betty, my column had a soft spot for drag queens and slackers (performance artists, in other words) and DIY types of all kinds.

I owe all this and a portion of my life to Bob, who treated my ideas with respect despite my half-formed, half-cocked character. Had Bob not hired me, encouraged and corrected my work and allowed me to believe I had some talent (and gifted me one Xmas with a Lucinda Williams CD), it’s possible I’d be working at an office job today. I’m truly, forever grateful.

It mattered then that it was on paper; I don’t think that’s the key point anymore, but it was good then. I worked with Talent: with dedicated photographers like Rudy Giscombe (RIP), who made photographing cows a master-class in lighting and composition; and talented designers like Blynda Barnett, whose compositions told the story and made me gasp with happiness; and genius-level writers like Charles Mohnike (having Charles as calendar editor was like having, I don’t know, Lee Hazlewood working on your records—and check it out, he’s creating an archive of Chico music online … right … now). Speer’s work and that of others who preceded me, such as the evocative Kim Weir, showed me that writing was art and craft. And the newspaper showed me that words, news, imagery and information could change things, and did.

I left Chico in 1996 to become editor of another alternative newspaper, the Honolulu Weekly, and I’m still a writer in Hawaii, though that paper folded years ago. But working with the Chico News & Review was the experience that made me—like Chico itself, heaven, hell and all points in between. I had the time of my life.

Joe Martin

Contributor (1983-1996); staff writer, news editor, associate editor, editor-in-chief (1996-2000)

I lived in Chico from 1980 till 2000, and throughout those years, reading the new CN&R every Thursday was as essential as morning coffee. It was my window into everything happening in town that week, from whatever the city council was arguing about to what bands were playing at Hey Juan’s. I started contributing to the paper as a student intern, and then as a freelancer, and eventually worked there full time for 9 years.

It’s funny, but I can barely remember anything about the news stories I covered, though they all seemed important at the time. What I do remember is the people: the CN&R staffers who became lifelong friends, and the various politicians, activists, actors, musicians, gadflies, cops, criminals, business folk, and downtown goofballs I probably would never have gotten to know if it hadn’t been my job to find out what they were doing and write something up for next week’s edition. The newspaper really was my way of connecting with the community, and what an interesting community it was. I’m sure it’s still as filled with interesting people and readers who want to know about them as it was in the ’80s and ’90s. I hope and believe the online version of the CN&R will find a way to keep telling those stories.

Peter Hogue (aka Juan-Carlos Selznick)

Film critic (1978-2024)

By some peculiar stroke of very good luck, I was teaching literature courses in the English Department at Chico State when a remarkable group of young writers and future journalists turned up in my classes. Joe Kane, K. Patrick Conner, Steve Metzger, Joe Martin. Two of them, Kane and Conner, were part of the group that founded the Chico News & Review; Metzger has long been a frequent contributor to the paper; and Martin was chief editor for a time. And all four were teammates of mine on the Pests, a slow-pitch softball team whose continuing history parallels that of the CN&R. (I first met Jason Cassidy much the same way, at Chico State, only a little later on.)

Kane and Conner knew I was also teaching cinema studies and publishing some film criticism. In the second year of the paper’s existence, they invited me to become the CN&R’s movie reviewer, and I leaped at the opportunity. They gave me carte blanche on subject matter, and accepted my decision to use a nom de plume—Juan-Carlos Selznick. (My reasoning was that Peter Hogue the academic might take weeks to compose a three-page essay—the pseudonym gave me the freedom to wing it, thoughtfully, for 500 words on a weekly deadline.)

Early on, I’d watch a film on its opening weekend, and the review would appear on the following Thursday—which was something of a disadvantage with films that had only a one-week run locally. All that changed for the better when Tim Giusta and Roger Montalbano at the Pageant Theatre started getting early delivery of upcoming films in order to provide preview screenings. Those private previews made it possible for my reviews to appear the day before the film in question had its Chico premiere. And so much the better for all involved, since most of the films I chose to review did not have the benefit of blockbuster advertising.

K. Patrick Conner

Staff writer (1977-1978 and 1982-1984)

It’s fair to say there would be no Chico News & Review if not for the Chico State Wildcat.

In its earliest incarnation, the News & Review was produced by essentially the same staff that produced the last issues of the Wildcat. We were refugees from the English and journalism departments, mostly—passionate, eccentric, not without talent. A handful of knuckleheads and trouble-makers, too.

True, the office was a madhouse, an asylum, really. The music could get loud. Empty beer cans occasionally rolled across the floor. It could be difficult to see through the smoke. There was silliness and laughter. There was outrage. On any given day, there were as many dogs in the office as editors.

But actual journalism took place now and then, some of it pretty damned good, often challenging the institutions that funded us, namely the university and the Associated Students. Truth to power can be an annoyance, and at our best, we could be highly annoying. It was that conflict that ultimately led to the founding of the News & Review.

I was sorry to see the Wildcat go, honestly. Working there was the most fun I’ve ever had in a newsroom. I’d go back and do it again in a second. I’m just as sorry to see the News & Review cease its print publication. It’s been a long and extraordinary run.

We all have our time and place, I suppose. But that doesn’t make it any easier to say so long.

Howard Hardee

Staff writer, calendar editor, contributor (2010-2017)

It had been my dream to be a writer since I was little, and the Chico News & Review was the first to pay me to do so. Working there as an intern in 2010 and as a regular staffer from 2011-2017 was one of the most exciting and fulfilling times of my life. Leaving Alaska in 2011 to take a part-time position as the paper’s calendar editor—which paid less than I was making sharpening hockey skates at a sporting goods store in Fairbanks—was a world-expanding decision. Right out of college, I snuck a toe into publishing and came to learn about art, music, the environment, local politics and the colorful characters of Butte County in greater depth than I could have imagined. I felt extremely lucky.

What I miss most are my old coworkers and the everyday rhythm of working in downtown Chico—early morning walks through Lower Bidwell Park and Annie’s Glen, filling my canteen at Peet’s Coffee, doubling back to Second and Flume, bounding up the back stairs and bursting into my shared office with then-arts editor Jason Cassidy. He’d be all like, “Word,” and I’d be like, “Jason, killer,” and then we’d both put on headphones and jam out stories. Ken Smith—hired as a staff writer within a few months of me joining the CN&R and a close co-conspirator throughout my time at the paper—would regularly excuse himself from the newsroom to the arts office to talk about music, heavy life stuff, or some heinous decision the city council had made the previous night, before stepping onto the back porch for a cigarette.

I miss cruising out on wacky assignments with Kyle Delmar, one of our many talented freelance photographers. I miss listening to former editors Bob Speer and Tom Gascoyne recall obscure local lore. I miss longtime designer Tina Flynn asking for someone to explain, in great detail, from the beginning of time, the origin story of a particular photo. I miss the Wednesday afternoon meetings after we put the paper to bed, in which we’d discuss how that morning’s calamity was to be avoided next week and maybe even plan a few issues ahead. Shoot, I even miss those pull-out-your-hair mornings under deadline pressure. I can hear my old boss Melissa Daugherty’s distressed voice—“Is that story coming?” And did I snap a photo? “Yeah? Oh, thank God.” “It needs a better caption than that,” Managing Editor Meredith Cooper might chime in. I miss the boisterous laughter from Alec Binyon’s, and later Jamie McCormack’s, office suggesting that the sales team was having a much better time than we were.

I can clearly hear the rhythm of Jason’s All Stars heavily ascending the back staircase followed by the semi-broken screen door crashing shut on the second floor of the CN&R building. Close my eyes, I can smell the musty newspaper smell of the place. Sometimes, I’ll get a little sappy and stop to put my hand in the handprint I made in once-fresh concrete in the parking lot. The initials and handprints of some of my former colleagues are there, too. They are all fading. The building is going to be an investment office now.

The loss of the print newspaper is, for me and many others, the symbolic passing of a special time and place that still feels close enough to touch. I am proud to have been there. I loved it unreservedly.

David Philhour (aka Dr. PMT, Paul Maddox Taylor)

Process camera operator (1980-1982)

I joined up with this band of journalistic merry pranksters in the fall of 1980 when they were paying themselves with Tommy Tutone t-shirts left over from the not very successful fundraiser for the CN&R held out at the Silver Dollar Fairgrounds. I was hired on to operate the gigantic Robertson flatbed process camera that occupied two rooms in the space above Nellie’s on Second Street. I was charged with creating half-tone enlargements or reductions of photos, and line shot for copy using a process called photo-mechanical transfer. Hence my name, Dr. PMT.

What a fascinating group of creatives, politically astute, and riotously funny group of comrades. Ideas kept bouncing around the office like silver balls in a mad-cap pinball machine, and the score just getting higher and higher. The editorial staff were the flies in the ointment of those who would, with dreams of greater profit, turn Chico into San Jose. With such luminaries as Gary Fowler, Kevin Jeys, Kim Weir, Danny Pollack, Juan-Carlos Selznick and a host of contributing writers the copy was insightful, well-researched, sometimes shocking, sometimes hilarious, often with a touch of Gonzo.

The production rooms were a bustle of creative energy with Tina Flynn, Mark Thalman, Kevin Cahill, Steve Barbaria, Mark Ulriksen, Merlin, Tricia Macdonald, Jennifer Atkinson. On production night the music of Charlie Robinson would float up through the floorboards from Nellie’s downstairs. Otherwise Bruce Springsteen, the Stones or some other exceptionally hip group would be blasting out from the boombox as many hands crafted the look of the paper as they hunched over their light tables. Back in the darkroom for the process camera, Dr. PMT was blasting the songs of Ituri Rainforest, Pygmy music collected by anthropologist Colin Turnbull. Lizanne Sandbach Fowler was there at her CompuWriter churning out galleys to hand to the proofer and then off to the paste-up crew.

Out pounding the streets, trying to sell ad space to the merchants who were often opposed to and appalled by the editorial stance of the paper, were Kim Tackett and Rosemary Febbo. They tried their best to keep this ship afloat and raise enough money to keep the presses rolling. And never forget Steve Silberman (Presto Silbo), who valiantly distributed each weekly issue into the hands of an eager readership. Those were the halcyon days, but the money was running out.

Staff meetings epitomized the collective spirit of the CN&R in those days, where every voice was heard and every opinion was discussed. A true work of democracy …. but that was not to last.

I raise a glass to those who took the Wildcat off campus to become the irreverent voice that was the CN&R. Also to the new management that kept the boat afloat for these many years. May the CN&R sail on in cyberspace though it will no longer line the cat boxes and parrot cages of Butte County.

Kim Weir

Staff writer (1977 and 1980-1981)

It was all about the news from the start, for me—that start being the Chico State Wildcat. Community news. Because the town desperately needed a second newspaper, to keep the daily Chico Enterprise-Record honest.

The E-R of the 1970s had become a mean-spirited mouthpiece for Chico’s old guard. Those who enjoyed most of the benefits of life in a thriving college town—especially the money vacuumed up by mom-and-pop businesses and real estate rentals. But the money wasn’t enough. Still the good ol’ boys needed to demonize college people. The E-R did its part by viciously attacking some truly decent human beings, distorting their actions and beliefs in the process.

The E-R’s journalists were not the problem. Most were quite good, bird-dogging story details and reporting them fairly. If there was news bias, it came from the bosses, from back-room decisions about which topics would get covered. About which stories lived, and which died.

The paper’s viciousness came from then-Editor Bill Lee, the scribblings of his poison pen perhaps representing others’ views. Those gleefully malicious editorials were dark works of art. And if the E-R’s targets wrote in to complain—or worse, request a retraction—the attacks escalated, getting still more unhinged. People lost jobs and careers, friendly neighbors, long-time friends.

I grew up in Chico when it was that town. Most of you reading this would not recognize it, despite the physical familiarity. People with even mildly liberal leanings had no safe place in public life. Smug certainties and self-righteousness snuffed out open community conversation. It was appalling. Someone had to do something.

The best public protest we Wildcatters could muster, in the mid-1970s, was an April Fool’s Day spoof, a sendup, the Chico Enterprise-Retched. Mostly spot-on, from its smarmy tone and snarky editorials to tips on finding clever new uses for grandma’s tiny silver spoons. A hit! So much so that amused E-R staffers raced over to grab entire bundles of Enterprise-Retcheds, to pass around back at the office.

As April fools and otherwise, Wildcat reporters kept at it, covering complicated topics and doing a steadily better job of it. Stories such as:

The need to protect rich agricultural lands in Butte County from urban development, to fully support and value the local farm economy. The need to end illegal four-by-four lot splits—essentially condoned for ages by the Butte County Board of Supervisors—because they effectively circumvented land-use development standards about housing density, roads, property access, and health and safety. (Illegal land subdivisions contributed to the 2018 Camp Fire disaster.) The need to fold Chapmantown and other cast-off, low-income, unincorporated areas of Chico into the city, so all community residents could enjoy political representation and essential services.

Community news was also a strong suit at the Chico News & Review, once the CSU trustees nudged the one-time student newspaper into a new identity and off campus.

But it was stunning nonetheless, in 1981, some time after I’d joined the CN&R news crew, when Chico voters filled all four open seats on the city council with liberals—public pariahs no more.

It was always all about the news, and continuing the community conversation.

Evan Tuchinsky

Editor-in-chief (2006-2009); contributor (2010-2015); contributing editor (2016-2024)

I first learned of the CN&R six months before coming here. My wife’s family lived in Paradise; we visited for Thanksgiving, and as avid readers, they had a stack of issues by the living room.

Flash forward to April: I walked through the door at Second and Flume, got a quick orientation at the front desk, then walked upstairs to the editor’s office. I met Chrisanne Beckner, the interim editor who hoped to return to her real job writing for the SN&R as soon as possible; Bob Speer, who’d agreed to return on a contract that, I quickly learned, expired at the end of the week; and the lone holdovers from my predecessor’s staff, calendar and arts editors Jason Cassidy and Mark Lore.

The cover story that week profiled another new guy in town, then-City Manager Greg Jones. I don’t remember much of the first few days except hiding under my desk when folks weren’t looking and wondering, “What have I gotten myself into?”

But things turned around fast. Bob agreed to stay as news editor, willing to give me a chance—and accepting that I’d already hired an associate editor, Meredith J. Cooper, with whom I’d worked in Riverside. (She was traveling the world and wouldn’t arrive till June. She’d accepted the job from a callbox in London.) Jason and Mark were Jason and Mark: funny, friendly and unflappable.

Readers also were willing to give me a chance, even those who doubted I’d succeed as a successor. My boss’s assignment for me helped immeasurably: Jeff vonKaenel gave me a list of 30 people to meet in 90 days, and 29 of them—from council members and county supervisors to business leaders and community activists—shared their local knowledge with me. (I still haven’t met Ken Grossman of Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. … maybe some day!)

Our group of writer/editors, contributors and interns carved our own identity. Bob and I had the temerity to endorse a conservative for City Council—somehow, the world didn’t end!—and my columns became known for taking on so-called friends (see: “Frenemies of the park”) as well as so-called foes (see: “Chief concerns”). A feature on 9/11 conspiracy theorists drew a sharp rebuke from a Chico State journalism professor who liked me even less after we revealed one of his students apparently plagiarized AP in her Orion article.

We also continued the award-winning legacy of the CN&R, most notably with a feature story by Richard Ek that spurred a series of follow-ups on city pensions, long before anyone else sounded the alarm. The California News Publishers Association recognized Ek for his reporting and the CN&R with its public service award. Our opinion section, news, arts and design (i.e., Tina Flynn) also rated among the state’s best. We expanded environmental coverage with the GreenWays section.

When I left, 100,000 readers were picking up the CN&R each Thursday. The staff, which by then included future editor Melissa Daugherty, kept putting out must-read issues weekly. I started freelancing for Bob and Melissa after moving out of state; when I moved back, Melissa brought me in on three occasions as contributing editor, the News & Review’s equivalent of a professor emeritus.

I’m proud of that point in the paper’s history. Even more, I’m proud of the people. We were, and remain, family.

Bill Unger

Distribution driver (2007-2024)

Eight-track tapes, the typewriter, disco, film, and yes, print media. What do they all have in common? Hands please.

As part of the CN&R delivery staff for many years, I’ll miss my gig, driving 150 miles to such places as Artois, Proberta (let’s hear it for Proberta!), Gerber, Dairyville, etc.

I’ll also miss the personal relationships I’ve developed over the years with other CN&R employees, both past and present. After the Camp Fire, the CN&R really felt like a part of my family (the good part). As Camp Fire survivors, my wife and I (like so many others) have really appreciated the hundreds of articles and great writing you have provided on this topic.

Thanks to the CN&R for providing us with such thorough coverage for over four decades. Also thanks for having the testicular fortitude to print alternative points of view. I’ve personally had two letters printed that were quite critical of the paper. (Geez, just what does it take to get fired around here?)

Lastly, thanks to Ken Smith, Evan Tuchinsky, Melissa Daugherty, Ashiah Bird, Jason Cassidy and all the other writers.

I will miss holding the paper and physically turning the pages. The good news is the CN&R will still be online and I look forward to reading the latest political, entertainment and other news online.

The CNR was the best guide to navigating my move to the area in 2001. It helped me understand the nuances of local politics, arts, education, and business. It made Chico a weirder and more wonderful place. I appreciate its brave choices over the years and hope the move online will allow it to continue to have a much needed voice in the Chico zeitgeist. Since moving to Humboldt County two years ago, I continue to make a monthly donation to the CNR and have faithfully read the online edition. I hope many others will do the same.

It’s good to see George Thurlow here. He and Bob Speer were supportive when I applied to the University of Iowa.

I’ve only published two commentaries in the CN&R, but its founding inspired me to protest, not on the streets, but in words. I was in my 40s when I finally studied journalism, but even then, newspapers were in decline. We had a community weekly called the Icon in Iowa City, an independent weekly, but it did not survive. Most other newspapers, minus The Daily Iowan, the university’s student newspaper, were conglomerate-owned.

All print newspapers are in trouble today, and college newspapers are not so great for those who know the CN&R’s history. Even up the street at Wayne State College in Nebraska, the student newspaper adviser lost his job recently when he let students publish something college administrators did not like. I knew Max; I took his class in communication law, and he was a good instructor and editor.

The students of the fledgling CN&R survived. Hurrah! And, as best I know, the Sacramento and Reno News & Reviews have survived, too. I didn’t realize there was a Santa Barbara News & Review, but neat. Every community should have a second news source. “Publications survive when they give readers what they want…” (Tracy, J. F., 2007, “A Historical Case Study of Alternative News Media and Labor Activism: The Dubuque Leader 1935-1939”).

Good alternative, community reporting, is getting out and talking to people. Chico residents should pool resources to keep their alternate monthly newspaper in print, including volunteering as reporters and helping maintain a website — not to replace the print issue but to fill in the gaps between publications. And not just in Chico, but everywhere. If we don’t, I think we’ll lose our democracy.

I hope things work and that the online CN&R thrives. But I’m not sure websites will help bridge today’s horrific divide. Still, I’ll keep my fingers crossed and hope another oldster like me, or someone else, isn’t rubbing his hands with glee over at the Chico Enterprise-Record.

I was a reporter for the Enterprise Record from 1978-1982. When I was fired (basically for being too liberal, though most other E-R reporters were too but better at hiding it) the New & Review saw me through some lean times as a contributor until I landed new reporter gig. As Pete Seeger put it, Wasn’t that a time, Oh, wasn’t that a time!j