Jim Brobeck is a long-time Butte County water advocate, water policy analyst for AquAlliance, and the environmental community representative on the Stakeholders Advisory Committee for the Vina Groundwater Sustainability Agency.

The mature urban forest of Chico and valley oak woodlands of Butte County exist because of the Tuscan Aquifer. This system underlies the valley floor portion of several Northern Sacramento Valley counties and the lower Tuscan—the pressurized deep portion of the aquifer that supports the overlying water table–is literally the foundation of the quality of life for all that thrive here.

The water table provides baseflow to streams and water to our deep-rooted trees. The Tuscan baseflow below connects tributary streams to the Sacramento River, allowing Chinook Salmon migratory pathways between their foothill/mountain spawning waters to the ocean as well as critical rearing refuge for young salmon.

If used conservatively, the Tuscan Aquifer can even sustain our homes, businesses and farms as we face the uncertainty of prolonged drought. However, if overuse tips the system out of balance, we risk losing this buffer altogether.

What follows is an attempt to provide a basic foundation of understanding of this most vital resource by answering some general questions about how water works in Butte County.

Where does Butte County get its water?

Surface water, groundwater and precipitation.

According to the 2016 Butte County Water Inventory, the valley floor portion of Butte County consumes 715,000 acre-feet of surface water diverted from rivers and streams (Feather River, Sacramento River, Butte Creek) and 411,000 acre-feet of groundwater pumped primarily from the Tuscan Aquifer system annually. (One acre/foot = 325,851 gallons and is enough to fill an acre with one foot of water.)

The surface water provides irrigation for rice cultivation and wildlife refuges.

Groundwater is used predominantly for irrigation of orchards and annual crops. Groundwater is also the source of water for urban and industrial use. Chico, for instance, uses about 20,000 acre/feet of water per year.

Precipitation provides an estimated 914,000 acre-feet of water annually to agriculture, streams, wetlands, oak woodlands and urban forests.

What is an aquifer?

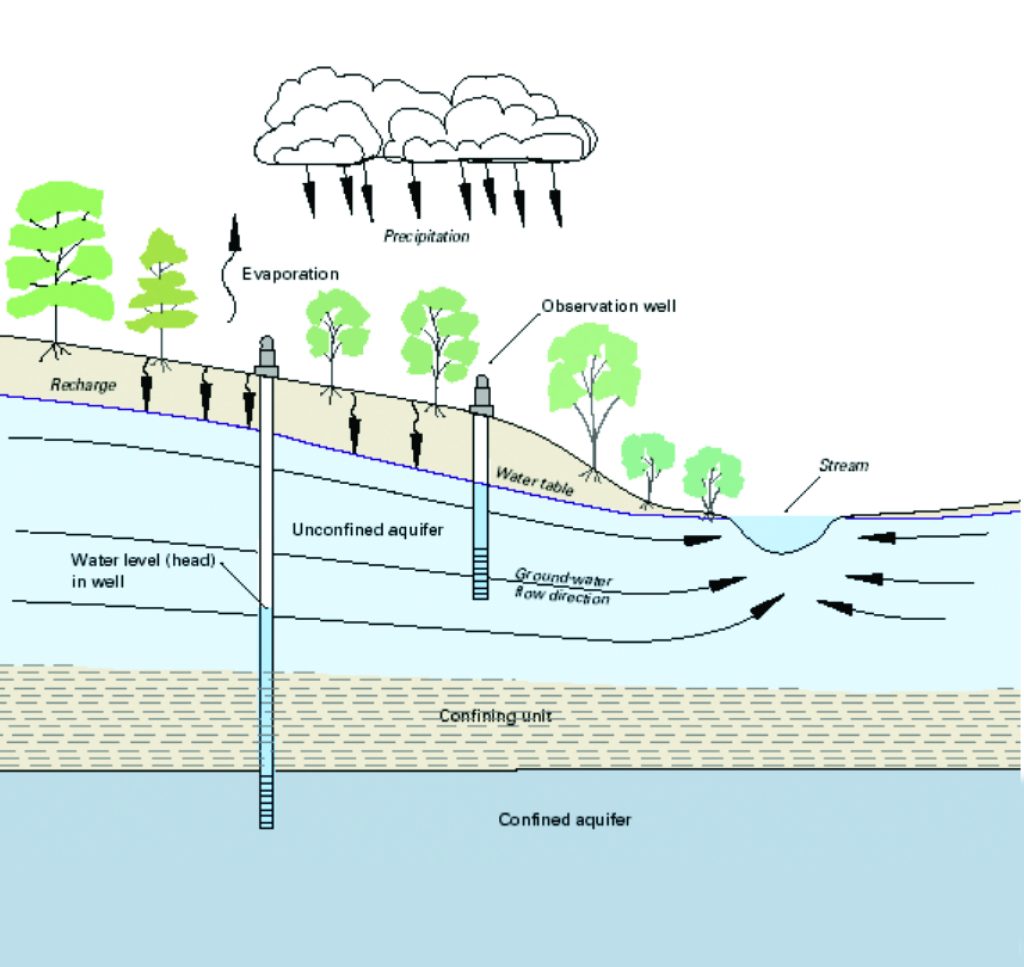

An aquifer is an underground structure of porous or fractured rock, beds of gravel and sand or silt that can absorb transmit and store water. There are two general types: unconfined and confined.

The water table is an unconfined aquifer that is connected to the regional aquifer system. Deep rooted trees can reach into the capillary zone just above the water table. When the water table extends to the surface it creates springs and supports streamflow.

A perched aquifer—a type of unconfined aquifer—can form when a lens of impermeable material is located above the water table. Percolating precipitation can collect in these areas. A perched aquifer is isolated from the regional aquifer system and is a less reliable source of water.

A confined aquifer underlies the unconfined layers. In the Sacramento Valley, confined aquifers are recharged (by rivers, creeks and precipitation) at locations above the valley basin and are located under geologic layers of nearly impermeable aquitards created by periodic volcanic flows. The elevated origin of recharge results in pressurized conditions below that can push upward, supporting the regional unconfined water table above.

What do we know about the Tuscan Aquifer below us?

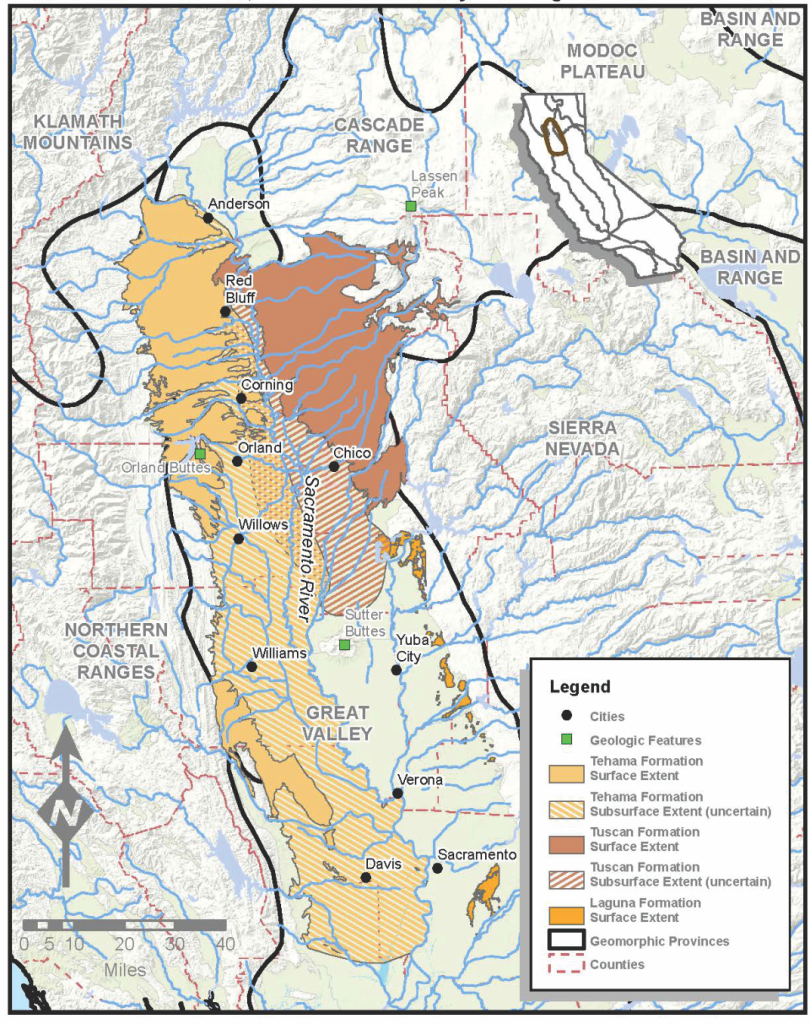

While it is known that the aquifer is the foundation of the hydrology that sustains the ecology and economy of much of the Northern Sacramento Valley, an accurate characterization of the system is still uncertain. Some experts describe the Tuscan Aquifer as a multi-layered groundwater system that underlies the North Sacramento Valley from Red Bluff to the Sutter Buttes, and from the edge of the Sierra Cascade foothills on the east and westward under the Sacramento River into Glenn County as far west as Orland and Willows.

The lower Tuscan Aquifer is about 500-700 feet below the surface in Chico, 1,100 feet in Hamilton City and up to 1,500 feet below Orland. Isotope analysis by the California Department of Water Resources indicates that the “age” of the groundwater ranges from under 100 years to tens of thousands of years. Wells in the lower Tuscan Formation along the eastern edge have the youngest water, and the deeper wells in the western and southern portions of the valley have the oldest water.

The aquifer system is often depicted as layered like a lasagna, but new studies show it to be more complex in structure. Chico State geology professor Todd Greene—a faculty associate for the university’s Center for Water and the Environment—describes it as more like a bowl of spaghetti with interconnected stream channels buried by overlapping sediment, including concrete-like volcanic mud flows.

In either case, geologists seem to agree that the lower Tuscan contains paleo-channels, remnants of rivers or streams that have been filled or buried by younger sediment which gets cut into and eroded by subsequent generations of streamflow. Another Isotope study—commissioned for Butte County between 2015-2017—indicates that the lower Tuscan is replenished by precipitation in the foothills and mountains on the eastern side of the valley. The recharged water flows slowly into the Sacramento Valley under cemented Tuscan lava cap creating a pressurized lower Tuscan Aquifer that helps support the shallow aquifer above, which supplies streams, capillary moisture to trees and fresh water to most of the domestic wells in the basin.

The model of the Tuscan Aquifer that I envision is not based on pasta varieties but on arterial circulatory systems: pressurized arteries (deep strata Tuscan) that flow to ever smaller blood vessels and capillaries (the shallow Tuscan). Like a circulatory system. the smaller vessels need to have arterial pressure to function. But gravity has a role to play. If the lower Tuscan is lowered by groundwater pumping, the upper layers drain down well casings and permeable layers while being pulled toward the large extraction wells.

How much water is in the Tuscan?

The aquifer system is not a bathtub. The pumpable water is in layers of gravel and sand, while the layers of clay and volcanic mud flow do not produce water. The fresh water moving through the Tuscan Aquifer may be 20-23-million-acre feet.

A healthy environment requires a balanced water budget, so only a small portion of the total water can be safely extracted. Wise use would limit pumping to the amount that is naturally replenished minus the amount that must provide baseflow to streams and other groundwater dependent habitat. In the San Joaquin Valley pumping has greatly exceeded recharge over the past century, causing groundwater levels to fall as much as 400 feet in places. This has resulted in shallow wells going dry, oak woodlands fading and dramatic land subsidence to spreads—sinking nearly 30 feet since the 1920s in some areas—damaging buildings, canals and roadways. As the water pressure has dropped, well bore perforations have allowed the water table to leak downward through the confining beds into the evacuated lower aquifer.

How is the Tuscan utilized today?

The shallow unpressurized aquifer at the top is the source for many domestic wells as well as groundwater dependent ecosystems, including the Chico urban forest. Historically, irrigation wells have tapped this unconfined aquifer.

The confined pressurized aquifer below is the source of Chico’s municipal/industrial supply and most of the recently developed agricultural wells on both sides of the Sacramento River. Irrigation district infrastructure was designed to divert river flow to irrigate crops. But during recent decades, water districts have punched many new wells into the lower Tuscan Aquifer to supplement their surface water supply.

What’s the status of our aquifer?

The overall level of the Tuscan Aquifer is trending downward as the cumulative impact of increased extractions exceed natural recharge.

The citizens of Chico have done a great job in cutting the amount of water used—by over 30 percent during the past few years.

Some data indicates that orchard crops in Butte County are not adding acres, however, that’s not the case in other counties in the Tuscan region. Investor-owned agricultural enterprises west of the Sacramento River continue to break ground on new orchards. New demand on the aquifer is expanding as water districts supplement supplies during dry years when river diversions are reduced. Senior districts in Glenn and Colusa Counties market portions of their river allotments and replace them with groundwater.

The greatest decline in aquifer level is occurring in Glenn and Colusa Counties. In Butte County declines have been noted around Durham.

Agriculture pumping in the North Valley is connected to subsidence here as well. It’s occurring near the I-5 corridor between Arbuckle and Orland where, since 2018, the ground has irreversibly dropped more than 2 feet in some areas. The cumulative impact on the shared North State aquifer appears to contribute to the overall decline in groundwater levels all the way into Butte County.

The true scope of any decline is still unknown. According to hydrologists at Chico-based Davids Engineering, “[The] ultimate effects of pumping can occur significantly after pumping starts, or even after pumping has ceased. The timescales involved in aquifer responses to pumping and other stresses can be on the order of decades, making it difficult to associate cause with effect. In general, the longer the timeframe for effects to be observed at a given monitoring point once they become evident, the longer those effects will persist, even if the pumping causing the effects is halted immediately.”

How is our groundwater managed?

Groundwater extraction by agriculture in the region is, with the exception of well spacing regulations, unmanaged. Farms certainly pay to develop wells and to operate the pumps, but there are no limits on how much water is used. Municipal customers on the other hand have been encouraged by state policy and rate-tier pricing to conserve water.

What is SGMA?

SGMA (pronounced “sigma”) is the acronym for the California Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. This 2014 legislation was a response to the extreme land subsidence and water-quality issues resulting from a century of groundwater overuse in the San Joaquin/Tulare basin and other smaller basins in the state. Sustainable groundwater management under SGMA seeks to avoid “significant and unreasonable undesirable results.” SGMA proposes that groundwater management is best accomplished at the local level, and Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) around the state have been charged with drafting Groundwater Sustainability Plans (GSPs) to help meet this challenge.

The final GSPs were due in January of 2022, and the final plan for the Vina subbasin—one of the main groundwater sources for Chico and the northwestern portion of Butte County—was approved by a Vina GSA board made up of one representative each from five entities: Butte County Board of Supervisors, Chico City Council, Durham Irrigation District, agricultural well-user stakeholder, and domestic well-user stakeholder.

Representatives from the environmental community (including this author), domestic well owners, business associations, Cal Water, Butte College and Chico State were chosen to participate in the Stakeholders Advisory Committee (SHAC) alongside numerous agricultural pumpers.

The submitted GSP has drawn criticism from several members of the advisory committee who are concerned that the potential increased pumping of the aquifer allowed in the final plan could cause more domestic wells to go dry, lead to depleted streamflow, and desiccate both urban forests and oak wooodlands.

Closing words: Honor the carrying capacity of resources

Century-long mega-droughts during the Medieval period (especially between 900 and 1350 CE) forced the native peoples of the Southwest to abandon their civilization. But the people living in the great Central Valley were able to endure these dry periods. Robust aquifer systems provided the buffer needed for oak woodlands to persist and for streams to connect with rivers for anadromous fish like salmon to complete their life cycle. The Tulare Lake region has been continually inhabited for more than 10,000 years. The lake, the rivers, and the groundwater supported perhaps the largest population of Native Americans north of Mexico.

Even during the paleo mega-droughts the Sacramento Valley of Northern California maintained a rich, diverse environment that supported some of the densest populations of non-agricultural people in the world. Groundwater migrates slowly downstream and modest amounts of precipitation allowed the basin aquifers to remain in balance with the ecosystems like oak woodlands and salmon spawning/rearing streams to remain intact.

Paleosalinity records that reveal salinity conditions in the western Delta as far back as 2,500 years ago indicate that the last 100 years are among the most saline of periods in the past 2,500 years. One hypothesis is that depleted groundwater conditions allow salt water to intrude into the Delta.

Great Valley aquifers have buffered the impacts of the mega-droughts. If the Tuscan is drawn down during dry periods to meet regional and state-wide demand, we risk the destruction of that protection. Domestic wells will go dry. Streams will leak away. Valley Oak groves will be eliminated. The Chico urban forest will wither.

True sustainability identifies and honors the carrying capacity of resources.

Thank you for this informative article. An informed public can push leadership into better decisions. Would you please consider extending this into a series? What aquifer recharge methods are being implemented in our regions?

Artificial recharge projects carry significant legal consequences that can lead to privatization and over-use of aquifers. The Tuscan Aquifer can and should operate under natural recharge regimes. Groundwater management here must focus on demand management, conservation and defending the public trust. The emerging groundwater market is a tremendous threat to the stability of the water table. AquAlliance.net

Jim, I enjoyed this article and learning about the Tuscan Aquifer for our region. I learned briefly about this during my Butte College geology course; are there any resources you’d recommend to learn more about our local aquifer?

Jim: What is the possibility of connecting to the Sacramento River for Chico’s residential water needs? Quality could be improved and supply would be almost limitless? I know that Davis and other cities have done this.