And the seasons they go round and round—Joni Mitchell

December, 1891, the YMCA International Training School, Springfield, Massachusetts. It’s cold, northeastern-U.S. cold, and the association’s young Christian men need a way to work out indoors during the winter months. Enter Dr. James Naismith, Canadian physical-education instructor, assigned by his supervisor to come up with a game to allow the athletes to train inside until spring thaw.

Naismith’s plan: two teams of nine, with the simple goal of tossing a soccer ball into two peach baskets nailed to the balcony at either end of the school gym, plus 13 basic rules, including:

A goal shall be made when the ball is thrown or batted from grounds into the basket and stays there. If the ball rests on the edge and the opponent moves the basket it shall count as a goal.

The Springfield YMCA sponsored the first public game of “basket ball” three months later. In March.

Of course, these original games had to be stopped after every goal so a janitor could haul a ladder onto the “court” and climb up to get the ball. It’s unclear who brilliantly suggested cutting holes in the bottoms of the baskets so that the ball could be pushed out with a stick.

The YMCA, along with the U.S. Army, continued to be an important early advocate of organized basketball, arranging international matches in 1893 in Paris, India, Japan and Persia (Iran). In February of that year, Nashville’s YMCA team played Vanderbilt, the first American college to field a basketball team. Two years later, Minnesota A&M (now the University of Minnesota) beat Hamline University 9-3 in the first recorded college match-up. The next year the soccer ball was replaced by a ball of Naismith’s design.

Most sources agree that the first modern college game (five players per team, not nine) pitted the University of Chicago against the University of Iowa, in 1896. The following year, the Amateur Athletic Union took over management of college basketball from the YMCA, and in 1905, a year before hoops, nets, and backboards were introduced, 15 colleges joined forces to create “The Basket Ball Rule Committee,” which, in 1909, morphed into the National Collegiate Athletic Association. In 1939, the NCAA sponsored its first annual tournament. Eight teams. Oregon beat Ohio State for the title.

That same year, Henry V. Porter, a ref from an Illinois high school, first used “March Madness” to describe college basketball—though the term wasn’t used to describe the NCAA Division 1 Tournament until 1982, when CBS sportscaster Brent Musburger introduced it in his broadcasts.

Shortly after the end of World War I, my father’s father, Pennsylvanian Henry Metzger, a stateside veteran of the war, was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Told he had six months to live, he married his girlfriend, the (very) Irish Catholic Alice Rooney. Disappointed with the care they received at a veteran’s hospital in Virginia, they headed for the southwest, where, according to the medical prognostications of the day, he’d have a much better chance of surviving the disease. They settled in Prescott, Arizona, where their first son, James, was born in 1922. Shortly after, they purchased a house on South Virginia Street, not far from downtown, where second son Robert was born, in 1925. Thomas (my dad) was born in 1929, Paul, in 1935.

(Robert would go on to join the US Army Air Corp, training as a night fighter flying out of Chico Army Airfield in 1944. He was killed in November of that year when his P-70 went down just outside of Roseville.)

My grandfather, on disability and unable to work, converted the garage of his new home to a pool room and the back yard to a basketball court. He was also an amateur filmmaker, experimenting with innovative angles, filters and points of view in otherwise generic home movies. He also served as an assistant to Ernest McFarland, Arizona governor and chief justice of the Arizona supreme court, also known as the “father of the G.I. Bill,” having sponsored the bill that Franklin D. Roosevelt signed in 1944. Our family lore is that Henry wrote the actual text of the bill, though I’ve been unable to confirm that. Aides are rarely credited with behind-the-scenes real work.

Meanwhile, the pool hall and basketball court became the weekend and after-school hangout for my dad, his brothers and their pals, and was known, unofficially, as the Prescott Boys Club. So my dad grew up shooting pool and basketballs. In fact, he was so good at pool that his dad would take him around to the local pool halls, including the notorious joints downtown on rowdy Whiskey Row, hustling the arrogant, unknowing sharks, the kid confidently sinking unlikely shot after unlikely shot as his dad collected their winnings.

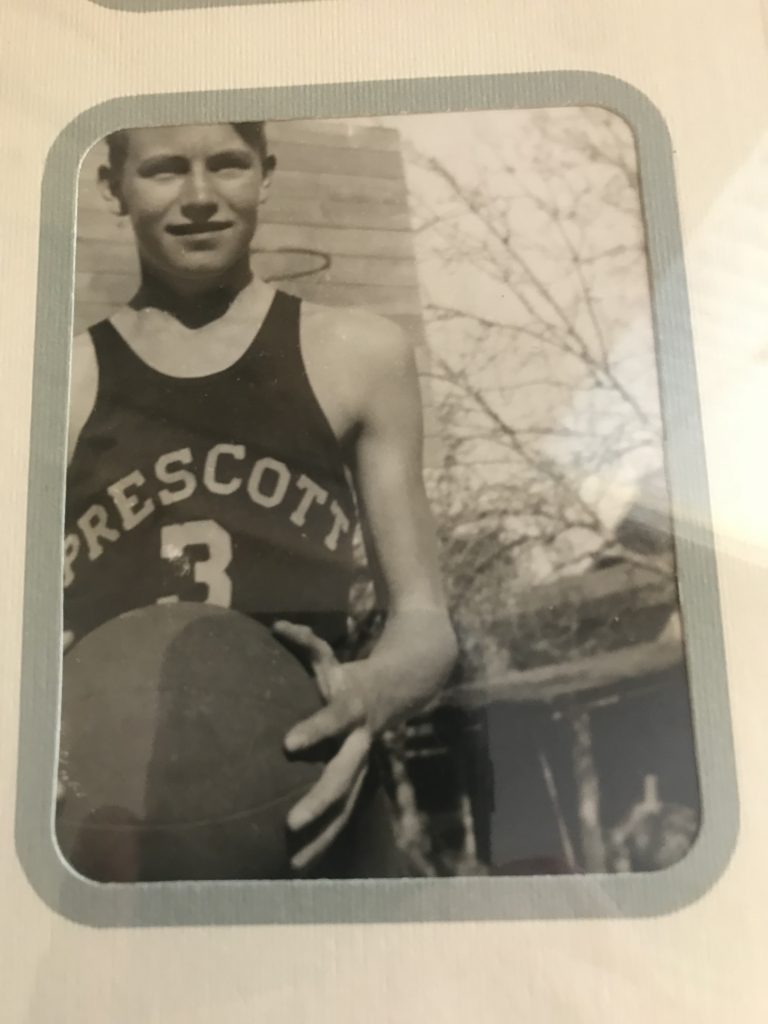

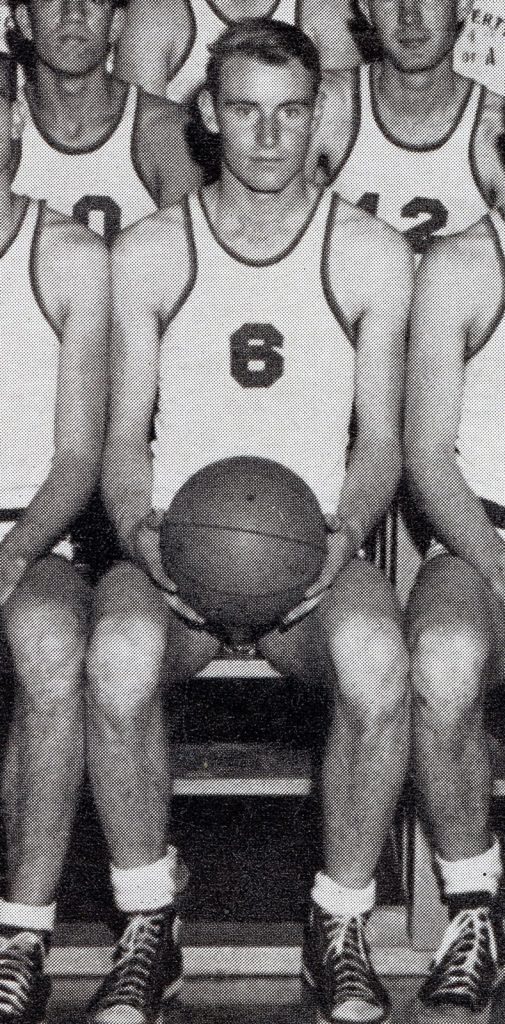

Prescott High School didn’t have a pool team, but they did, of course, have a basketball team, and by his senior year, my dad, a 6’3” center, had established himself as the star of the Prescott Badgers. That year, 1949, he was selected captain of the All-Arizona state team. He was also awarded a full-ride basketball scholarship to the University of Arizona, despite his so-so grades.

My grandfather died in 1952, at 57, having stretched the six months into 30 years.

After my dad moved to California, in 1953, to take a job as a highway engineer with Caltrans in San Francisco, he continued playing in Marin adult recreation leagues into his thirties. He loved telling us kids about the time he and his Arizona Wildcats beat the Harlem Globetrotters—more family lore that I have been unable confirm.

I didn’t get the basketball gene. Neither the player gene nor the fan gene. While I could always hold my own in a schoolyard pickup game, and I can watch a pro or college game with my pals, I was never the guy you’d go to in a big game as the clock ran down. Baseball? That’s another story.

That said, I played organized basketball off and on for much of my life, including in seventh and eighth grades, playing in tournaments against other Marin County junior highs. In October of 1969, my first year at Terra Linda High School, I tried out for the freshman basketball team. I knew my chances were slim, as I was competing with guys I’d been playing against the previous two years. Some of them were really good.

But I made the cut, barely, thanks in part, I’m sure, to the hours I spent shooting baskets in our back yard, my dad having assembled and installed a cheap Sears Roebuck backboard, hoop and pole on our little patch of concrete—especially playing HORSE with my brothers and sister, all afternoon, till it got dark and Mom called us in.

Turned out, I was the eleventh man. Which meant that as Coach Yamagata taught the plays to the first team, and the second team defended against them and learned the plays that way, we, the third team, watched from the sidelines where we were expected to learn the plays.

One day in December, we bussed across the Bay to play against some high school we’d never heard of. It was a non-league game, so the stakes were low, virtually non-existent.

Which is why Coach Yamagata started his third team, including me at forward.

I don’t remember much about the game—except being on fire. I scored 13 points, and we won 42 to something.

After the game, Coach Yamagata congratulated me, sat me down on a bench in the locker room and told me how proud he was of me and how he looked forward to coaching me in the future. I wiped a towel across the back of my neck and unlaced my white Converse high-tops (part of our required uniform). “I’m quitting,” I said. “That was my last game.”

He shook his head, as if in disbelief. “You can’t quit now.”

I shrugged. Truth was, most of my friends were spending their weekends skiing at Heavenly Valley, not running up and down inside sweaty gyms. It was, as they say now, a no-brainer.

Coach Yamagata looked me in the eyes. “I understand,” he said. “Just don’t turn into a hippie.”

When I told my dad at dinner that evening that I’d quit the team, he took a bite and nodded. “I hope that works out for you.”

In 1951, the NCAA Division 1 men’s tournament doubled to 16 teams, then doubled again in 1975 and yet again in 1985. Since expanding to 64 the NCAA has added a tourney play-in round—one game in 2001, upped to four games in 2011—which brings the total to its current 68 teams for both the men’s and women’s tournaments. Along the way, the country has grown more and more interested, especially as games were televised. Interested? Perhaps “obsessed” is a better word these days.

Yet, despite my dad’s love of the game, and long history with it, he wasn’t much of a fan, either of college or professional basketball. I can’t remember his ever sitting down in front of the television to watch a game—March Madness finals or NBA playoffs. On the other hand, my brother Rick recalls Dad taking him to several Warriors games in the 1970s. “He was always talking to the refs,” Rick says.

Dad also kept tabs, especially during March Madness, on his University of Arizona Wildcats. Who have done rather well over years: qualifying for the NCAA Division 1 Tournament 25 years in a row, from 1985 to 2009, reaching four Final Fours and two finals—in 1997 and 2001—beating Kentucky in the former and losing to Duke in the latter. This year they lost in the first round to Princeton.

Notable Arizona Wildcat basketball players include Mo Udall, U.S. Congressman from Arizona, U.S. presidential candidate (1976), and member of the Denver Nuggets (1948-’49); former Sacramento Kings point guard Mike Bibby; Golden State Warriors star Andre Iguodala; and current Golden State Warriors head coach Steve Kerr.

In 1979, I was invited to join the iconic Chico Area Recreation Department (CARD) softball team, the Pests, originally sponsored by George’s Pest Control, hence the name. From early April through October for over 25 years, highlights of my life—outside family—included Saturday morning practices and weekly games at the Hooker Oak fields and, later, Community Park (20th Street). One evening, drinking beer at the old Reddengrey Pub after a Fall Ball win, we were lamenting the season’s approaching end and the onset of winter. Someone suggested that we put together a CARD basketball team. A good way to keep working out indoors during the coming winter months. No objections. So for the next six or eight seasons I played for the Spuds (named for Spuds Mackenzie, the Budweiser dog), the basketball version of the Pests (as did Chico News & Review film critic Juan Carlos Selznick and former editor Joe Martin) in the gyms at Chico Junior High and Pleasant Valley High. At the same time, I’d joined Chico Sports Club and was playing with a group of the same 15 or 20 guys every Tuesday and Thursday morning starting at 5 a.m. Often we were showered and headed out to our cars before sun-up. That lasted about 15 years.

One day I rolled an ankle. Badly. Really badly. I lay on the court on my side, guys from both teams circled round me, my leg pumping like a pneumatic hammer gone berserk. As the doctor set my cast that afternoon, he said, “What were you doing playing basketball at 48?” I played for another few years.

Basketball’s a winter game, has been since 1891. So this year’s March Madness was especially appropriate here in California, with relentless rains most of the month, even some snow here on the valley floor. Lindo Channel and Big Chico Creek roared, trees uprooted; Tahoe was buried in snow; the Coast Ranges were blanketed peak to valley floor. By the end of March, California had recorded its deepest snowpack in 70 years.

I confess to paying very little attention to March Madness and feeling like it was marching off without me, not that it mattered.

But then it came down to the Final Four, April 1, still rainy and cold, and I was glued to the semi-finals. When San Diego State’s Lamont Butler sunk that buzzer-beater to eliminate Florida, a million basketball memories raced through my mind, about playing in junior high, countless hours shooting free throws in my parents’ back yard and at the outdoor courts at my elementary, junior and high schools, that half season on the freshman team, Chico CARD games, pre-dawn games at Chico Sports Club, and about my dad.

In 2006, he was inducted into the Prescott High School Athletic Hall of Fame.

He died in April, 2015, of Lewy body dementia, spending his last few months in a small room in an assisted-care home in the East Bay, hallucinating about his days as a young man.

Basketball is a winter game, but Monday, April 4, two weeks into spring, was clear, with deep blue skies and a crisp morning breeze. In Houston that afternoon, the San Diego State Aztecs were playing the University of Connecticut Huskies in the finals of the NCAA tournament. March Madness.

I tuned in at game time. I didn’t have much of a dog in the fight (not even a Huskie), although after teaching at Chico State for 30 years, I was kinda pulling for San Diego State. They felt like compadres, especially since they were the underdogs.

Final score? UConn 71, San Diego 57.

But I didn’t mind losing: After all, it was baseball season, and my Giants had trounced the White Sox in Chicago earlier in the day, 12-3, with seven home runs, including four in one inning to tie a 12-year-old franchise record.

The home opener at Oracle Park was less than a week away.

And spring was here.

Steve: Great memories and even a better journal of your grandfather & father’s life which are also your’s. Great recollection and the memory of Hank Y will never fade from my past TLHS days. Appreciate the share and inclusion in great memories. Justy got me thinking of much we thought we know someone, and realize there is much hidden behind the curtain. Thanks for rolling back those curtains.

Jon

Glad you enjoyed it, Jon. Thanks for reading and taking the time to respond. I hope all’a well. S.