This story was produced by CalMatters, an independent public journalism venture covering California state politics and government. For more info, visit calmatters.org.

Two winters’ worth of snow has already fallen in the Sierra Nevada since Christmas, pulling California from the depths of extreme drought into one of its wettest winters in memory.

But as a series of tropical storms slams the state, that bounty has become a flood risk as warm rains fall on the state’s record snowpack, causing rapid melting and jeopardizing Central Valley towns still soggy from January’s deluges.

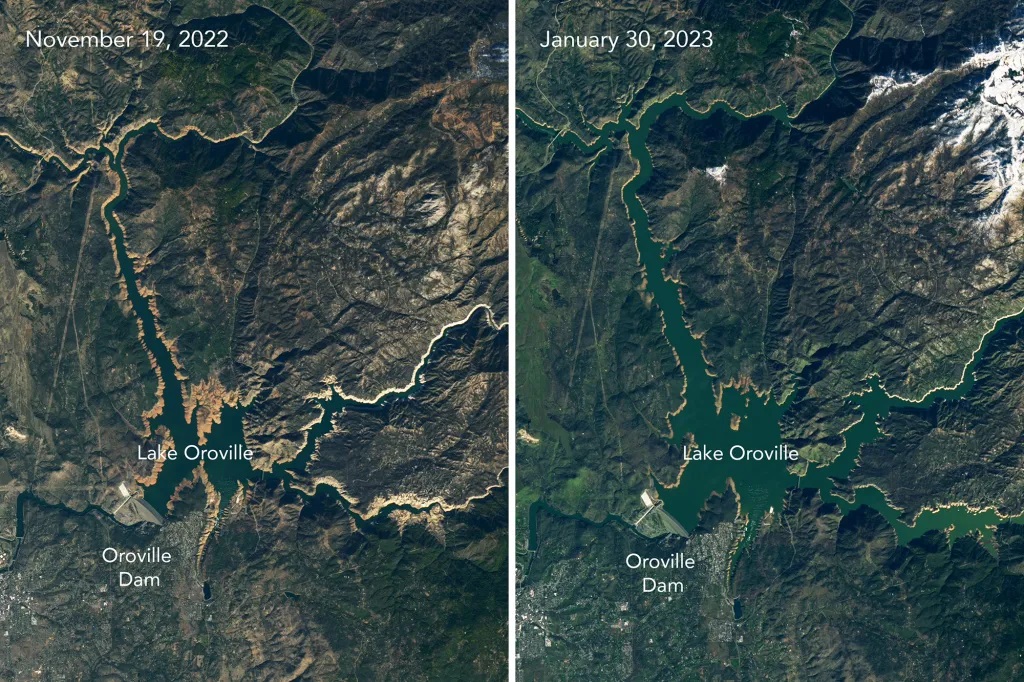

The expected surge of mountain runoff forced state officials on Wednesday to open the “floodgates” of Lake Oroville and other large reservoirs that store water for millions of Southern Californians and Central Valley farms. Releasing the water will make room for the storm’s water and melted snow, prevent the reservoirs from flooding local communities—and send more water downstream, into San Francisco Bay. The increased flows in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta could help endangered salmon migrate to the ocean.

So what’s the downside? These same storms are prematurely melting a deep and valuable snowpack that ideally would last later into the spring and summer, when farmers and cities need water the most.

The storms have created a tricky situation for officials who manage state and federal reservoirs in California, since they have to juggle the risk of flooding Central Valley communities with the risk of letting too much water go from reservoirs. They must strike a balance between holding as much water in storage, as long as they can, while maintaining room in reservoirs for more water later in the season.

“Water management in California is complicated, and it’s made even more complex during these challenging climate conditions where we see swings between very, very dry, very, very wet, back to dry. We’re now back into wet,” said Karla Nemeth, director of the Department of Water Resources.

Rivers in the San Joaquin Valley are forecast to flood today or Saturday. Eleven locations are expected to reach the flood stage, although no “danger stage” flooding is anticipated, according to Jeremy Arrich, deputy director of the Division of Flood Management with the Department of Water Resources.

To make room for more water, state and federal officials who manage California’s major dams and reservoirs are releasing water. Some will flow into the ocean—which aggravates many water managers, Central Valley legislators and growers, who often say freshwater that reaches the bay or ocean is wasted. However, efforts are underway to divert much of the released water into depleted groundwater storage basins.

On Wednesday, the Department of Water Resources increased outflow of water from Oroville from about 1,000 cubic feet per second to 3,500 cubic feet per second. By Friday, total releases could be as high as 15,000 cubic feet per second, according to Ted Craddock, deputy director of the State Water Project.

Oroville is now more than 75 percent full, containing 2.7 million acre-feet of water—up from less than one million in the beginning of December. In spite of releases, the reservoir’s level will keep rising. Craddock said inflow in the next five days could hit 70,000 cubic feet per second. That’s about half a million gallons of water per second.

In 2017 Oroville’s levels reached so high that the overflow water damaged its spillway. An emergency spillway had to be used, eroding a hillside and triggering evacuation of about 200,000 people in nearby communities.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation announced a similar operational move for Millerton Lake, the reservoir behind Friant Dam on the San Joaquin River, which supplies water to growers throughout the Central Valley.

The two-day rainfall totals will be “quite astounding” and “will lead to some really significant runoff,” said State Climatologist Michael Anderson. More storms are expected next week and later in March.

Rain on snow

Today’s storm is creating what watershed scientists and weather watchers call a “rain on snow” event. Earlier this winter, freezing elevations hovered as low as 3,000 feet, meaning precipitation above that fell as snow.

That has changed, Anderson said. Freezing levels have risen to as high as 7,000 feet in the southern and central Sierra Nevada, where the bulk of the snowpack has accumulated. A National Weather Service forecast shows freezing elevations even higher, at 9,000 feet, and warned that “snow will melt easily below 5,000 feet,” since it is already approaching the melting point of 32 degrees Fahrenheit.

State officials say the premature snowmelt from this storm likely won’t have much effect on supplies this spring and summer.

“This winter, there has been an accumulation of snow at lower to mid-level elevations, which will experience melt during this storm and will generate runoff into foothill and valley communities,” said David Rizzardo, manager of the state water agency’s hydrology section.

“However, at higher elevations, where the vast majority of the snowpack is, we will not experience significant melt. Even with higher snow levels above 8,000 feet in these storms, we still anticipate seeing additional snow accumulation at the higher elevations that will add to our snowpack totals, especially in the Southern Sierra.”

John Abatzoglou, a UC Merced professor of climatology, said deep, soft snow has the physical capacity to absorb a great deal of rain. The snow may even freeze the rain, rather than vice-versa, effectively increasing the snowpack volume, at least for a while.

“As you add liquid to the snowpack, it gets denser, it gets warm, and it gets more apt to melt when the next storm comes,” he said, noting that more atmospheric river events are coming next week.

Diverting underground

While the latest storms flood river valleys, state regulators have taken action to capture as much stormwater as possible before it flows into the ocean and use it to recharge groundwater basins.

On Wednesday, the State Water Resources Control Board approved a petition from the Bureau of Reclamation to divert 600,000 acre-feet of San Joaquin Valley flood waters into wildlife refuges and groundwater recharge basins. Diversions can begin on March 15 and continue until July.

“Given the time it takes for water to reach the downstream point of diversion at Mendota Dam, the approval period will allow for floodwater capture following storms expected this weekend,” the water board explained in a news release.

The action is intended in part to help meet Gov. Gavin Newsom’s goal of increasing groundwater storage by over 500,000 acre-feet per year, spelled out in his Water Supply Strategy released last summer.

But environmental groups protested the water board’s action.

Greg Reis, a hydrologist with The Bay Institute, said it will allow the bureau to divert all of the San Joaquin River except for 300 cubic feet per second—what he calls “a very, very small” amount of water. Floodwaters, he said, are important for ecosystem function and survival of fish, including threatened spring-run Chinook salmon.

He compared floodwaters in a river to a person’s increased pulse when they exercise.

“If you don’t get your heart rate up when you exercise, you don’t get the health benefits,” he said. “Same thing for a river. You’ve got to get the flows up, and the 300 cubic feet per second is certainly not adequate for a river like the San Joaquin.”

Be the first to comment