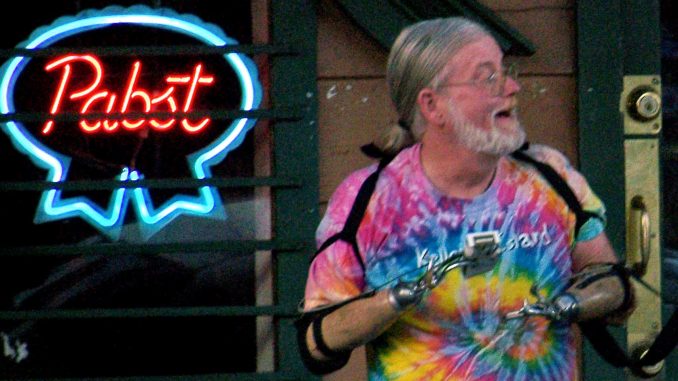

On Nov. 25, local icon Kelly Meagher died in his Butte Creek Canyon home. In memory of our longtime friend, the CN&R offers this condensed (and lightly edited) version of a story that ran in the Dec. 15, 2011, edition of the CN&R. Read Tom Gascoyne’s original full interview at newsreview.com/chico/content/hooked-on-the-cause.

That Kelly Meagher had a big impact on this community over the years is undeniable. He organized and funded numerous political campaigns, most in the name of environmental protection. More than anyone, he used his own money to support the causes he favors. He had wealth—though not as much as many other people in Chico—and he spread it around.

His generosity and financial ability to back it up helped launch a community radio station, kept the heart of the Butte Environmental Council beating during tough times, and funded numerous political causes—many successful, some not.

His once-red locks and beard turned silver, his once-fit frame a bit expanded, he was often found at his favorite perch on the west end of the bar at Duffy’s Tavern in downtown Chico, downing Pacifico beer and shots of Hornitos tequila.

Meagher was a community character, a fixture who loved to talk and drink; he was a pain to some, a savior to others.

Upon graduating from high school in 1970, and while in the process of trying to gain conscientious-objector status (he’d been drafted), Meagher went to work for César Chávez’s United Farm Workers union.

He worked as a union organizer for 2 1/2 years, before taking a job at a hospital in Fullerton for two years. He completed his government-required community-service work, and then moved to Berkeley, where he became a self-employed house painter.

“It was good living,” he said. “I was really a good little capitalist—I made a lot of money painting.”

He painted houses—inside and out—for the next 5 1/2 years. Then, on July 19, 1979—what Meagher referred to as his “rebirthday”—his life changed in a split second.

He was working on a four-story building in downtown Berkeley. Running parallel to the building was a thick black wire that emitted a pulsing buzz.

“I had learned enough in my painting time there to know that’s a dangerous wire,” he said. “It’s kind of close, too. So you could pay funds to this major utility and they would shut it off. I asked them to turn it off for two weeks while we finished the job.”

When the job was finished, he and another fellow removed the scaffolding.

As they were taking it down, a cross-rod broke loose.

“It was going to fall four stories down like a javelin and probably going to harm someone,” Meagher said. “It was on Shattuck Avenue right downtown. The hospital was right there. I could see it was going to hit the dead wire. And I thought, I can just hold it. Well, the wire was on.”

He joked darkly about what happened next: “It was a shocking experience, and I got a real charge out of it.”

He stayed conscious through the ordeal.

“I remember going up in the elevator at Alta Bates hospital and the doctor telling me, ‘I don’t think we can save your hands.’ And I looked at my hands and saw charcoal. I couldn’t feel them, I couldn’t move them. They were clinched. They were burnt black, black as night.”

He said he was in shock and felt no pain. He remained in the hospital about four months.

“I had a brilliant surgeon, but the nurses saved my life,” he said in typical Meagher style. “God bless the nurses.”

Before he left he was fitted with prostheses, “my hooks, as I like to call them.” By flexing muscles in his shoulders and back he could make them open, which enabled him to grasp objects such as glasses and eating utensils.

He filed a lawsuit against the power company, which he eventually won. He was limited by the structure of the settlement regarding how much he could say about it.

“I wasn’t defeated by the accident, but I was scared,” Meagher said. “Once I went on this river trip I knew that I could beat it. My goal was to be the same old asshole I always was. Well, guess what? I am.” The river trip, he said, was a life-changer.

In April 1980 Meagher came to Chico “just to check it out.”

He was hired by the Butte Environmental Council as an intern, and he later served on the board of directors and twice as general manager.

“That’s because we were broke and nobody else wanted to do it,” he said. “I ran the recycling center, but as [former BEC office manager] Carol Mueller will tell you, I spent most of my time at LaSalles and she ran the place.”

Meagher’s first foray into local politics was close to home—the plan to build 75 condos just below the house he owned in Butte Creek Canyon. This was the summer of 1980.

“I stopped by one night at a meeting the citizens’ committee was having, which was a bunch of housewives at the covered bridge. My roommates had told me, ‘Kelly, they’re going to build these houses down there and ruin the canyon. You know, these guys are the most powerful people in six counties.’ And I remember thinking, that doesn’t sound right.”

So he went to the meeting. He said at that time in his life he looked like Charles Manson.

“They were scared of me. … They were very suspicious of me and kind of uptight thinking I was going to do something evil. But I had a nice dog with kind eyes.”

He offered his help, and they handed him the draft environmental-impact report on the project and asked him to come back with his analysis.

“I went to the Chico State library and asked the head librarian for the law books on the California Environmental Quality Act,” he recalled. “I read the stuff, I read the report, I came back the next week. I gave them 20 pages that I wrote out in hook, and they went, ‘You’re hired.’ Although they didn’t pay me.”

He ended up as their spokesperson.

“They made me cut my hair, shave my beard, and they took me to J.C. Penney, where they bought me ‘good clothes,’ as they said. They made me take my earrings out. But it worked, you know? We did it.”

He was Chico-indie.com First Donation ever. We love you.