Gail Tozier placed her hand upon the bark of a dying olive tree in her Butte Valley orchard. The trees are over 120 years old, she said, and haven’t been irrigated since November 2018, when the Camp Fire raged through the foothills and destroyed the orchard’s life force: the Miocene Canal.

“It’s so depressing to look at them,” Tozier said with a heavy sigh.

Her family used to produce award-winning olive oils, but without water—save winter rains—the orchard isn’t producing viable olives. Tozier Ranch products have lost their spot on the shelves of many major and local retailers.

Tozier has yet to quantify the loss—even the trees that are still alive will “never produce like they used to,” she said. This year’s drought is a challenge for most farmers in California, but for Tozier and others in this portion of Butte County, long-term survival has depended on the historic Miocene.

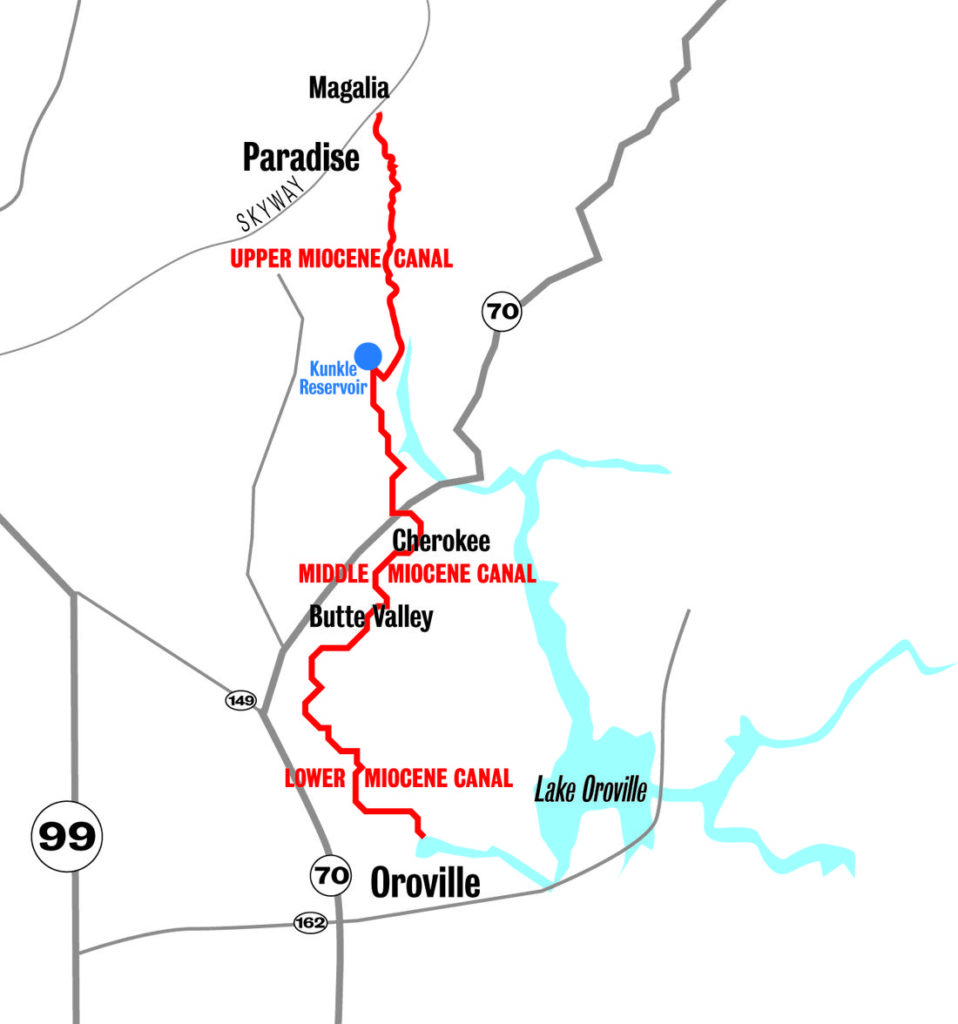

Life without the canal—which is largely owned by PG&E, whose equipment started the 2018 Camp Fire—has been devastating for farmers, ranchers and families living adjacent to the man-made waterway. Known for its series of flumes, the Miocene has run dry for three consecutive summers.

During that time, longtime agricultural users have called on PG&E to restore the infrastructure, not only to secure their livelihood but also to preserve wildlife and defend the region against future wildfires.

PG&E originally balked at the cost of repairing the canal, choosing to explore alternatives. In the meantime, it delivered some water to Miocene customers. Then, last summer, the company pledged to dedicate $15 million toward providing water access over the next five years while long-term solutions were explored.

But for farmers reliant on the Miocene, little progress has occurred over the past year. In fact, facing drought in addition to the loss of their primary water source, many feel more desperate than ever as they await news that could make or break them.

Last week, PG&E spokesman Paul Moreno said via email that engineering designs for repair of the Miocene should be completed by the end of this month. The plan will be used to determine requirements for permits and entitlements from local, state and federal agencies and for final review and consideration for approval by PG&E management.

And therein lies the rub: PG&E has not specifically pledged to embark on a rebuild, the cost of which is not yet public but is estimated to exceed the company’s initial commitment.

Moreno said that the company cannot speculate on what-ifs but added that “should PG&E not approve spending more than the committed $15 [million], the remaining funding would likely be used to continue to deliver water to local residents but would also be available to contribute towards other long-term water delivery solutions.”

Drop in the bucket

Since July 2019, PG&E has delivered 5,000 gallons of water per week to Miocene customers who’ve requested it. However, that volume of water is a proverbial drop in the bucket, farmers say—nowhere near what they need to irrigate thousands of acres of parched ag land and stave off future fires.

In 2020, PG&E began offering water deliveries to households that were never paying customers but had benefited from the Miocene leaking, creating a lush environment. The canal—a system of ditches and wood-supported metal channels—was originally created in the late 1860s or early 1870s by the Miocene Gold-Mining Co.

Recently, PG&E started delivering 10,000 gallons per week and 2,500-gallon water tanks to seven users who requested additional supplies, Moreno said.

For Kurt Albrecht, owner of Chaffin Family Orchards, PG&E’s deliveries have helped provide water for his cattle, but his family had to tear out 30 acres of dead and dying peach and apricot trees. They’re keeping 20 acres of citrus trees alive with water from a family reservoir that filled to only one-third capacity this year.

“We’re starting low on water and basically trying to spread the water thin enough to keep the trees alive to get through the summer,” he said.

It’s a financial hit that has required him to dip into savings to pay the bills and keep his employees on payroll. Chaffin Family Orchards has been farming at a loss for three seasons post-Camp Fire, Albrecht said.

The hardest part is the uncertainty, he added.

“At this point, we can’t even make replant plans, ’cause I don’t know if the water is gonna come back. [PG&E’s] actions have been so questionable. … I’m gonna wait till there’s water in the canal till we start planting,” he said.

Meanwhile, even domestic water use is a concern. Some families are rationing water for everyday needs such as showering and toilet flushing; dirty clothes are hauled to laundromats in town.

Ed Cox, spokesman for the Miocene Canal Coalition (an advocacy group made up of water beneficiaries), is familiar with such conservation practices. He’s spent $30,000 adding storage facilities to his property and pumping his wells to fill ponds that are used by his cattle and for fire suppression, he said.

And as much as he’s invested, he knows of neighbors who’ve spent more to secure water.

Everyone in the valley is hurting, he said, but the drought has made things particularly painful. In previous dry spells, the canal helped locals get by, Cox said. In his family’s case, it fed a nearby creek that ran year-round and kept his ponds full. The creek has since dried up.

“It’s a matter of survivability, not profitability,” he said. “What do you do? Do you sit your family down and say: ‘We have no water. Are we moving, are we going to try to sell our property and go ahead and move on?’”

‘Beyond frustrated’

Stakeholder meetings after the Camp Fire, including explorations of solutions such as installing a pipe to siphon water from Lake Oroville and connecting to Ridge irrigation districts, resulted in dead-ends. Tensions mounted between the utility and water beneficiaries.

At one point, Paul Gosselin, the former director of Butte County’s Department of Water and Resource Conservation, chided PG&E for its lack of substantive participation and told property owners to seek legal counsel and file in PG&E’s ongoing bankruptcy proceedings.

Though PG&E made the announcement last summer to commit $15 million toward restoring water access, a permanent long-term solution wasn’t specifically identified.

Butte County Supervisor Bill Connelly, whose district encompasses this portion of Butte Valley, said the county has participated in the meetings to “try to help the people there that have been dewatered.”

Connelly said that the county’s $252 million settlement with PG&E will be used for impacts to county government and infrastructure, not for impacts to individuals or privately owned utilities.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen until they come out with their [engineering] study and PG&E exposes themselves,” he said. “PG&E has kind of studied this to death, and they’re trying to limit their cost … In my mind, it’s unrealistic they can do it for

$15 million. So it’s really [up to] the [district attorney].”

Butte County District Attorney Mike Ramsey told the CN&R that PG&E’s pledge to dedicate $15 million to restoring water access to the canal was one made in “good faith”—made in a letter penned by former CEO and President Bill Johnson just before the company announced its plan to plead guilty to manslaughter charges for those killed in the Camp Fire.

“I am committed to finding a solution for these residents while PG&E works with the community to find a long-term plan to replace water previously provided by the Miocene Canal,” Johnson wrote.

In Ramsey’s view, “it certainly was the idea that that $15 million was to find that long-term [solution], be part of that long-term solution,” he said.

PG&E provided Miocene beneficiaries with a $15 million estimate for repairs years ago. “That figure came from some place,” Ramsey added. “The context was the belief that that would be the solution.”

He continued: “Is it enforceable? Enforceable in the court of public opinion, and I think PG&E is very concerned about that, let’s put it that way.”

For the two dozen or so residents along this stretch of rural Butte County who are are contracted water users, their recourse is the ongoing bankruptcy proceedings, he added. For those whose families have benefited from the canal’s seepage, the situation is “somewhat muddy,” Ramsey said, “by virtue of the fact that many of them had no water rights.”

Albrecht is one such water user—with a contract so old it is written in miner’s inches—who chose to file in the lawsuit for fire victims. He says he’s yet to see a payout and anticipates that “there’s no way we’ll get full coverage. But there might be something.”

Ryann Newman, whose family owns Aloha Ranch Inc., home of Ryann’s Happy Day Pony Ride and Fruit Caboose Concessions, received a USDA grant to help with the costs of installing a well at her property. This year, she was finally able to move her livestock back. They’ve been gone since summer 2019.

The well has helped, but groundwater access in the region is spotty even outside of drought years.

Newman expressed frustration at the drawn-out process of finding a solution with the utility company. According to a Butte County report from a Miocene Canal Workgroup meeting this past April, the earliest water could possibly be restored to the canal would be summer 2022, and that’s if PG&E decides to fund its repair.

“We’re basically at square one to this day. And it’s incredibly disheartening for landowners who’ve watched their crops dry and had to move their animals,” Newman said. “We are beyond frustrated, I can tell you that.”

Moreno of PG&E noted that the utility has spent time exploring myriad options for water access. Pumping water uphill from Lake Oroville and bringing in treated water from an irrigation district both proved unfeasible due to insufficient lake water levels, permitting and associated costs, he said.

PG&E has already spent nearly $1 million on water deliveries and expenditures with engineering firms, according to the county’s report. For Newman and others, this is worrisome—the concern is that the company will continue to provide insufficient water deliveries instead of dedicating the $15 million it pledged toward a permanent solution.

Moreno said that the $15 million was “broadly defined to support implementation of a plan to deliver water to local residents over the next five years,” and that the “costs to perform studies related to the evaluation of water delivery alternatives is consistent with the intended use of those committed funds.”

Scars from the Camp Fire

Even with the water deliveries, olive farmer and rancher Tozier has had to cull her herd of cattle. Her husband has been running their backhoe constantly in order to take the water PG&E delivers from one tank to the different cattle troughs.

“My husband and I are retired, and we’ve never worked harder in our lives,” she said. “How long will PG&E continue to bring us water? I have no idea. And if in fact they decide to rebuild the canal, how long will that take? There are too many unknowns.”

The uncertainty makes it impossible for anyone in the valley to make plans.

As Tozier took the CN&R on a recent tour of her property, the skies above began filling with a smoky haze from the Dixie Fire. That blaze has consumed at least 67 structures and more than 248,000 acres across Butte and Plumas counties since igniting on July 14, and Cal Fire is investigating PG&E equipment as a potential cause.

Last summer, the company pleaded guilty to manslaughter for the deaths of 84 people in the Camp Fire, as well as one felony count of unlawfully starting the 2018 blaze. Many victims who have filed in ongoing bankruptcy proceedings have yet to be compensated; meanwhile, KQED reported in May that the Fire Victim Trust in charge of compensating them has racked up over $50 million in overhead costs while disbursing $7 million to victims.

For Tozier, the specter of the Camp Fire lingers, especially considering the Dixie Fire and current drought conditions.

Cal Fire had not only used the Miocene to draft water to fight fires but had also drawn from ponds and springs throughout the area that are typically fed by the canal. Tozier’s property usually has ponds. Now, the landscape is bone dry.

“I’m just so afraid of fires again in this area, especially when we have no water to protect our property,” said Tozier.

“That’s the scariest part for me.

Be the first to comment