While driving north toward Oroville for a Feather River salmon fishing trip in August of 2003, a voluminous tree beside Highway 70 caught my eye.

“A fig tree!” I called from the backseat of my parents’ car.

My dad pulled over, and we walked back to the barn-size landmark and filled bags with small, brown-skinned figs, so ripe they were bursting open.

I was 24 at the time and had recently taken an interest in roadside foraging, and I was particularly excited about figs. I had grown up occasionally eating the Black Mission figs from my grandparents’ tree in Redding, but I’d never thought much of this fruit until I was in my early 20s.

That’s when I took up cycling, and on long rides, I noticed fig trees along roadsides in the Bay Area, the Delta and the Sacramento Valley. I began coming home to San Francisco with bags of figs of many colors, shapes and sizes. I dried the fruits, cooked them into chutney, brewed them into beer, and simply feasted on them. One autumn, I spent seven weeks cycling around California, eating almost nothing but figs.

My fascination drew me to Europe and Turkey, where fig trees grow in mind-blowing multitudes. They line the roadways, overtake abandoned villages, and seem to spill out of stone bridges and castle walls. Year after year, always in fig season, I bicycled in almost every nation between Gibraltar and the Caspian basin. I pedaled over mountains, deserts and islands, looking the whole way for the next fig tree.

I was, and remain, quite obsessed with figs—and it turns out I’m not alone. Across the nation, and the world, a community of fig-crazed gardeners has emerged in recent years. Doug Scofield, of Thermalito, is one of these fanatics. Almost anytime he drives someplace, he eyes the vegetation beside the road, looking for the distinctive foliage, scattered shades of green, large leaves and sweeping branches of a fig tree. While kayaking, too, he scans the riverbanks.

“They’re always going to be where there’s a water source,” he said.

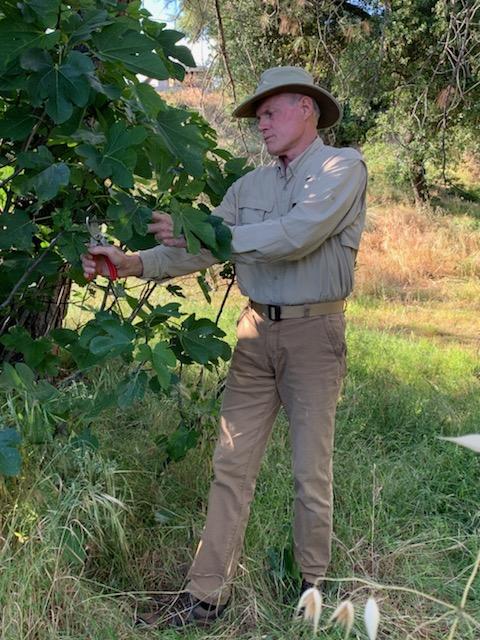

When he finds a tree bearing high-quality figs, Scofield clips off a few branches and brings them home, where the cuttings are easily rooted in pots. In a few months, miniature clones of the original tree are growing in his yard, and by year two or three, they begin producing fruit.

Scofield’s interest in figs goes back just eight years, but in that time, he has planted his 2-acre property with an astounding 700 fig trees, most of different varieties. Three-hundred are planted in the ground, while the rest grow in pots. He will freeze-dry this year’s crop for storage and also may market some commercially. Meanwhile, Scofield has been taking notes on each variety’s virtues and flaws, aiming to weed out the underwhelming ones.

He prunes his trees to keep them small, giving away the wood for propagation. There is no shortage of takers. While people have loved figs for millennia, social media—especially a number of Facebook sites and a forum called OurFigs—has amped-up the excitement while creating a hub for exchanging branch cuttings, the common currency of fig collectors. Scofield says he prefers sharing material, while others cash in on the excitement. At Figbid.com, a single fig twig, depending on the variety, can sell for anywhere from $5 to hundreds of dollars.

Naturally, the high demand fuels greed, and fraud. Scammers prowl internet auction sites, selling mislabeled cuttings at through-the-roof prices. Thieves lurk among the trees, too. Multiple times, people have trespassed onto Scofield’s property and made away with valuable trees or their branches. Now, Scofield labels his trees with numeric codes to thwart any prospective fig thieves. Other collectors protect their trees with barbed wire fences and security cameras.

Shadows of controversy shroud the online chat forums, too, cast by disagreements over varietal origins. Sometimes, trees of an established variety are “discovered” and treated as seedlings. They are given attractive new names and marketed as novel finds, generating hype and heavy cash flow, and buyers may unwittingly wind up with an extra of something they already have. Such renaming happens often, intentionally and accidentally, and it always has. The ancient Kadota fig is also called Dottato. The Black Mission fig was called Franciscana in Spain prior to its global conquest, and the Calimyrna—a staple of California’s industry—is simply Turkey’s Lob Injir relabeled for a new audience. According to Ira Condit, a fig researcher of the mid-20th century, the Brown Turkey fig has had more than a dozen synonyms.

Yet another prized heirloom variety, with mottled green-brown skin and strawberry-jam flesh, is believed to have originated long ago from a seed in the rocky soils of Croatia. Someone brought it to Louisiana decades ago. Its papers, so to speak, got lost, and today it circulates under the humble label of Smith.

The Smith fig, in fact, is one of my latest acquisitions. It arrived in my mailbox through a trade with a grower near San Jose. I’ve personally sold cuttings on FigBid but have found it more rewarding to give and receive—exactly how I have grown my own fig tree collection from about 25 varieties a year ago to 75 now. More will come.

The hobby can escalate out of control. In this niche community, many a driveway and patio has become clogged with black plastic pots containing some fig variety or another. Squeezed by limited space, many growers graft numerous varieties onto single trees—which they call “Frankenfigs”—and as soon as photos and positive reviews of a new variety appear on the forums, they scramble to get it.

As often as not, it seems, the next great fig emerges from California. Scores of new varieties—perhaps hundreds—have been discovered in the past decade alone in the state’s woodlands and creek canyons. In places like the Sacramento River basin, figs grow rampantly. They are treated as an invasive species by government roadway and watershed managers, and conservationists have decried their tendency to choke out native plants from riparian zones.

But for advocates, the fig’s proliferation has made the landscape a brighter place.

“It’s a big treasure hunt,” says Red Bluff fig buff David Burke, who has enjoyed figs all his life but became fascinated by the species about four years ago. Burke, who sells cuttings and fig culinary products under his brand “The Fig Hunter,” has created a map of California pinned with the locations of more than 1,000 roadside or riverbed figs. Most of his finds are from the Sacramento Valley, though he has found figs growing near Fort Bragg, at high elevation in the Mendocino Coast Range, and in Southern California.

“We found one outside the hotel at Disneyland,” he said.

Many of these fig discoveries are wild trees—and this is significant. That’s because a tree that sprouts from seed is a product of sexual reproduction and, therefore, genetically unique and probably growing nowhere else.

Seedlings tend to be easily identified simply by where, or how, they’re growing. A fig rooted in a cliff wall, a ditch, a thicket of poison oak, under a bridge, or in a creek bottom is almost certainly a wild tree, sprouted from a stray seed. Most such figs bear mediocre or downright inedible fruit—but often enough, a star is born.

The Yolo Bypass fig—green-skinned with dazzling, blackberry-red pulp inside—was found several years ago on the floodplains west of Sacramento. Cherry Cordial came from a private yard in Southern California, where it sprouted beside a palm tree. Raspberry Cream came from the flank of Table Mountain, east of Oroville; Holy Smokes from a Santa Barbara churchyard; and Crema di Mora from a roadside ditch near Chico. These figs and others join a vast ensemble of fig cultivars old and new from Eurasia and north Africa, where collectors similarly browse the river valleys and cliff faces for new prizes.

The common fig, or Ficus carica, is native to the Middle East, where scientists believe it was the very first plant species cultivated by early farmers of the Neolithic age, more than 11,000 years ago. Over the millennia that followed, the species spread outward in all directions, becoming essentially naturalized, if not technically native, throughout the Mediterranean and Caspian basins and eastward toward Afghanistan.

The fig came to the New World as horticultural baggage of the Spanish and Portuguese, and the species made its way across the continent with the missionaries. Fig trees reportedly arrived in California in 1769. For the next century, the trees—mostly of a few varieties, including the ubiquitous Black Mission—were confined to farms, private gardens, and mission churchyards.

Then, near the end of the 19th century, something remarkable happened: Fresno-area farmers planted Turkish fig varieties in the hope of launching a competitive dried fig industry. However, the trees’ fruits failed to ripen year after year. The U.S. Department of Agriculture investigated. The agency’s scientists conducted some studies, took some cruises to the Mediterranean, and in the late-1890s solved the mystery. Turns out certain fig varieties, such as those then planted around Fresno, require pollination—plus the presence of nearby hermaphroditic fig trees, called caprifigs, which produce pollen—in order to produce ripe fruit. So, the agency intentionally introduced fig wasps and caprifigs into the San Joaquin Valley, and by the turn of the century, the region’s Turkish fig orchards were producing heavy crops of ripe fruit.

The effort was successful, but it had an unforeseen consequence: Because fig pollination, also called caprification, makes fig seeds fertile, the introduction of the wasp to California allowed the state’s fig trees to sexually reproduce.

Seedlings began sprouting as they do in the Old World—that is, almost everywhere. Fig trees sprung from sidewalk cracks, rubble, irrigation ditches, creek gullies, suburban yards, hollows in other trees, and, perhaps more than anywhere else in the state, the fertile, moist soils of the Sacramento River valley.

“We have these huge thickets of figs out here,” Scofield said.

He browses these Ficus jungles regularly during the fruiting season—what he calls “fig safaris.” His grandkids sometimes join his scouting expeditions, and Scofield says they’ve become adept at spotting trees in the distance.

“They’ll shout, ‘Papa! There’s a fig tree!’” he said.

Scofield guesses that just one wild fig in a thousand will produce fruit worth noting on social media, but he has found several. A few years ago, he came across a wild fig tree laden with plump green fruits with jammy, berry-red pulp inside. He named it Thermalito, and it has since become a collector’s item.

More recently, Scofield found a fig that he swears is the best fruit he has ever tasted. He named the fig Angelito, and he mailed cuttings to just one other grower, Eric Durtschi, a fig collector who lives in the suburbs of Santa Barbara.

Durtschi became interested in figs back in the summer of 2018, and in barely two years, he acquired 800 fig varieties—a collection he has since halved.

“I tend to go all-in when I try something new,” he said, noting that he previously focused his gardening science on blackberries, corn and other common backyard crops.

Brian Melton, in Fresno, has about 400 varieties on his property, and Rigo Amador, a collector in Florida who helped launch a site called Fig Database, says he has cataloged roughly a thousand genetically unique figs growing in the world’s collections, and there are almost certainly thousands more.

So prolific are private collectors that they have outpaced even government germplasm collection programs. The UC Davis-USDA Wolfskill Experimental Orchard, near Winters, used to be regarded among hobbyist fruit growers as the bearer of the torch when it comes to rare figs. The facility still serves as a gene bank for many tree fruit species, but its 300-something fig varieties, many acquired through labor-intensive expeditions to Albania, Georgia and Azerbaijan, represent just a fraction of the Ficus carica gene pool.

The proliferation of new varieties on the market has, in some opinions, blown out of control. By some estimates, a new variety is introduced almost once a week during fig season.

“All these new, terrific figs keep coming along, but if you’re chasing new seedlings, you can’t keep up,” said Gary Pennington, a gardener and fig collector in western Sonoma County.

(Photo by Doug Scofield)

Pennington has focused his collecting mainly on established varieties, grown for centuries in Europe. Nearby, in Sebastopol, Achilles Stravoravdis is building a backyard fig library oriented toward berry-flavored varieties. Bassem Samaan, a Pennsylvania collector and owner of the Trees of Joy online nursery, is known for his assembly of Middle Eastern figs.

Durtschi says he particularly enjoys growing—and tasting—California seedling figs, though he shops overseas, too. He once spent $600 for a small copy of a tree called Cessac, found a few years ago growing from the crumbling ruins of a French castle (a classic European example of fig wasp progeny). Such expenses may even out; Durtschi says he once sold a Boysenberry Blush fig tree for $1,025.

Superstar status is generally short-lived for any fig variety. The Swiss fig called Ponte Tresa became so hotly sought after five or six years ago after a few photos of its dripping red interior floated across the internet that the mother tree was hacked apart by enthusiasts who wanted a piece of it. The fervor cooled as copies of the tree circulated and spread, and today Ponte Tresa is relatively commonplace. Some collectors have even said it was, after so much fuss, overrated.

A well-known passage in the Bible calls for prosperous men to sit beneath their own fig tree. I often think of this as I walk among my own trees, for nearly all are less than three feet tall.

But figs grow quickly, and even this summer, I expect my small trees to reach head-height and bear a substantial crop.

“What are you going to do with them all?” a neighbor asked.

“I can eat a lot of figs,” I said.

I have about 30 small trees in the ground, and while I certainly don’t need many more, it sounds like the Angelito fig is a must-have.

Durtschi recently told me that a fig called Colonel Littman’s Black Cross is perhaps the best he’s tasted. It, too, is now on my wish list.

Other varieties will arrive unexpectedly, I know. A neighbor fig grower recently invited me over to collect some extra trees. I drove over and filled my car with eight potted trees, including the highly regarded Genovese Nero, Hative d’Argenteuil and LSU Tiger.

“Where does it stop?!” I recently wrote to a trader as we negotiated an exchange.

“It never ends,” he replied.

Alastair Bland is a longtime News & Review contributor who writes about the environment, agriculture, science and food.

Thanks Alistair for including us in your passion. And thanks for sharing that jammy one with me.

Jim

As a single mother of four, heavily rooted at home, I do not lead a life of such great adventure, but I enjoyed reading about yours. I, too, am in love with figs. Thanks for sharing.

Wonderful article! Thank you so much! I have been following California fig discoveries very closely. We lived in Chico and would take the kids out for long walks on country roads and in the summer we ALWAYS found a “wild” fig tree and enjoyed their fruit as a special treat. I had no idea that these figs trees would become famous!