Photo courtesy of Cal Fire

Fire safety has suddenly become far more politically fraught and expensive. Here, firefighters respond to 2017 Ponderosa Fire, a 4,000-acre blaze that destroyed 32 homes and numerous outbuildings in the Forbestown area.

Don’t be fooled by the precipitation, the snowpack, the wildflowers. It’s unlikely that California’s iconic landscape will sustain the moisture to withstand the 100-degree summer and fall.

California has yet to recover from the five-year drought that began in 2012. For four years, record wildfires have ravaged the state, including the Tubbs Fire in Napa and Sonoma in 2017 and last year’s Camp Fire. The 2019 wildfire season officially kicks off in mid-May, but California’s wildfire season is essentially year-round now.

So what happens when the next big wildfire hits?

State fire officials are already amassing new aircraft that drop thousands of gallons of bright-red flame retardant. Emergency responders are pre-positioning fire crews in high-threat areas. State officials will no longer second guess the use of wireless emergency alerts that grab people’s attention by making smartphones vibrate and squawk.

The major investor-owned utilities—Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric—now plan to shut off power, even where fire risk is minimal, during red flag weather warnings. It’s considered a public-safety measure of last resort because a power outage can cut off internet access and make communication difficult for hospitals, firefighters and emergency personnel.

The utilities also plan to fireproof California’s electricity grid, a result of their equipment being implicated in so many recent disasters. That includes clearing brush and trees away from transmission lines, replacing wooden poles with metal ones, and using drones and weather monitoring stations to gauge danger via wind and smoke patterns.

Yet even these expensive precautions may not ward off the next towering inferno, say fire officials.

“I think we are better prepared,” said Kelly Huston, deputy director of the state Office of Emergency Services. “The real question is whether or not that’s enough.”

‘A sense of urgency’

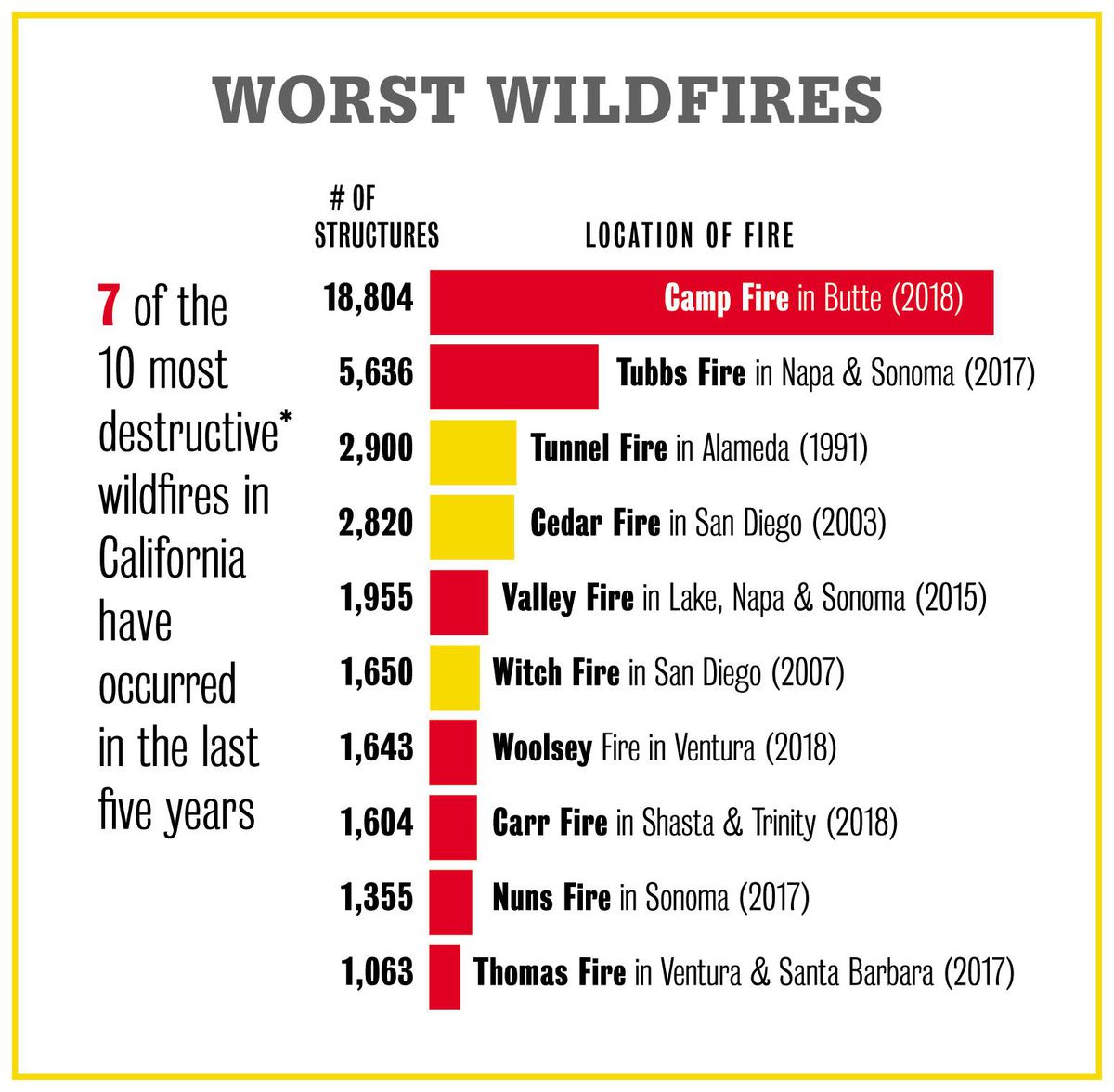

Part of the problem is that California has been caught off guard by the new climate-driven fire seasons, amplified by longer hot summers and extended droughts. Seven of the 10 most destructive wildfires in state history have happened in the last five years.

“The fires are behaving so much differently than they have before,” Huston said, noting the new wildfires are “virtually impossible to fight” as they leap mountains and gallop for miles, creating their own weather systems. “You couldn’t have predicted this based on past fire.”

Photo by Cyclonebiskit via Creative Commons

Malibu residents flee the Woolsey Fire. The blaze started on Nov. 8—the same day as the Camp Fire—and killed three people. It destroyed more than 1,600 buildings.

California Public Utilities Commission President Michael Picker told state lawmakers on Jan. 30 that climate-change-driven wildfire is happening much faster than anyone predicted. But for the state regulatory agency to enforce safety at the state’s eight investor-owned utilities, Picker said, he would need 15,000 to 20,000 new staff to police every electricity pole and wire. The agency has, roughly, a 1,300-member staff.

The CPUC regulates not only privately owned utilities from telecom to water, but also rail crossing safety, limos and ride sharing. Historically, Picker’s role has been more like that of an administrative judge than a police chief.

“If you want to get the Legislature to allow me to be a total dictator, make decisions overnight, I’m happy,” Picker elaborated to reporters. “That’s not what our job is. We are like a technical court. People have to have their day in court. It’s not a fast process. Have you been in a court proceeding that took one day?”

But his answer on the challenges of enforcement frustrated lawmakers, on whom political pressure has mounted with every disaster. The CPUC is not known for swiftness. It took nine years to issue a statewide fire-threat map after Southern California fires, caused by Santa Ana winds whipping power lines, prompted commissioners in 2009 to demand one. It has laid out a two-month schedule just for reviewing fire prevention plans utilities must submit under recent and hard-fought wildfire safety legislation.

After Picker’s testimony, Democratic Assemblyman Jim Wood, a forensic dentist who represents fire-ravaged Santa Rosa, took to Twitter.

“I want to hear a sense of urgency,” he wrote. “We don’t have time for a standard bureaucratic approach.”

Amassing ‘more tools’

Ultimately, the fire challenge involves painful long-term decisions such as how to reconcile the acute demand for California housing with the suddenly limited supply of land that isn’t in a high-risk fire zone.

Short-term, Democratic state Sen. Bill Dodd of Napa is among those who hope incremental improvements might make a difference. He is proposing the commission work with Cal Fire and the Office of Emergency Services to improve coordination for turning off power in red-flag weather, alerting residents to evacuate and better targeting crews to fight fires. His bill, Senate Bill 209, which cleared the Senate’s Governmental Organization Committee last week, would establish an official, statewide California wildfire warning center.

“It would give us more tools in trying to make sure this doesn’t happen again,” Dodd said.

Emergency officials also are studying past fires, and preparing. Survivors of the Tubbs Fire in Napa and Sonoma counties complained they had little or no warning when the flames flared up at night under dry windy conditions. Local officials opted against sending out a mass alert for fear of causing panic or hindering emergency responders.

“Everybody I talk to in our neighborhood pretty much either had family call or a neighbor knock on the door. I don’t know of anyone that got an emergency alert,” said Patrick McCallum, a higher education lobbyist who barely escaped his Santa Rosa home with his wife, Sonoma State University President Judy Sakaki. “Worse, there were police and fire engines running around but they were not allowed to put their alarms on.”

Butte County residents escaping the Camp Fire experienced similar issues with inadequate or nonexistent warnings.

The state is expected to soon issue clearer guidance to all 58 counties for issuing alerts and warnings to the public across multiple platforms. The new thinking is to over-communicate, rather than rely on the alerts of the 1980s sent over television and radio or ringing landlines.

“It is something people depend on to make decisions in a crisis,” Huston from OES said.

The state also believes pushing out wireless emergency alerts on smartphones similar to an Amber Alert can now be done effectively without creating chaos. This simple weather warning was sent out to seven counties encompassing 22 million people in Southern California in December 2017 as a precaution after authorities saw dry windy conditions similar to the wine country fire two months earlier:

“Strong winds overnight creating extreme fire danger. Stay alert. Listen to authorities.”

This fire season, Californians may see it again.

A firefighting air force

Meanwhile, Cal Fire is beefing up its capabilities. And rather than waiting to respond to a wildfire, emergency personnel have shifted to pre-positioning strike teams before a fire even starts.

The switch comes at a price; Cal Fire’s expenses now already routinely exceed its budget. Last year’s fire spending set a new record, and the political climate has made the outlays difficult to question.

“That’s expensive because you’re paying the same amount of money for firefighters whether they’re fighting a fire or sitting waiting for a fire to start,” Huston said. “But you have to weigh that against the potential for loss and the expense of a disaster.”

The state already boasts a formidable firefighting air force, featuring S-2T air tankers that dump 1,200 gallons of flame retardant and Huey helicopters for lifting fire crews in and out of steep terrain.

This spring, the Hueys will start to be replaced by more modern Black Hawks, the Army’s frontline utility helicopter. The first one is expected to be ready in May, said Cal Fire spokesman Scott McLean.

Photo by Melissa Daugherty

A motorcycle ditched along the side of a road in Magalia was among the hundreds of abandoned vehicles reporters witnessed in the days immediately following the Camp Fire. Eighty-five people died during the blaze, the deadliest and most destructive in state history.

And over the next two years, Cal Fire will add seven C-130 Hercules cargo planes. Those will be retrofitted to carry between 3,000 and 4,000 gallons of flame retardant.

“California will have one of, if not the largest, firefighting air forces in the world,” McLean said.

What about the utilities?

At ground zero in much of the state are California’s investor-owned utilities and their spark-prone equipment. PG&E has vowed to expand power shut-off territory to as many as 5.4 million customers, up from 570,000 today. Southern California Edison is focused on better weather monitoring, adding 62 high-definition cameras and 350 micro weather stations as part of a broader $582 million safety plan.

And San Diego Gas & Electric, which has been most aggressive with more than $1 billion in safety upgrades, will continue to replace wood poles with steel poles, hire a helitanker on standby year-round, and contract with firefighters specially trained to put out electrical fires.

Yet there’s no statewide standard for deciding when the power should be shut off. Instead, participating utilities base decisions on temperature, wind, humidity and other factors. San Diego Gas & Electric has been lauded for its proactive use of public safety power shutoffs.

PG&E’s rollout has been less reassuring.

Two days before the most destructive wildfire in California history ignited, 62,000 PG&E customers in eight counties, including Butte, were warned that their power could be turned off as a precautionary measure.

“This is an important safety alert from Pacific Gas and Electric Company. Extreme weather conditions and high fire-danger are forecasted in Butte County. These conditions may cause power outages in the area of your address. To protect public safety, PG&E may also temporarily turn off power in your neighborhood or community. If there is an outage, we will work to restore service as soon as it is safe to do so.”

—6:30 p.m. Nov. 6, 2018

Cal Fire reports the Camp Fire ignited around 6:30 a.m. on Nov. 8.

PG&E never shut off power. In fact, the utility went on to issue cancellation notifications hours after the deadly blaze started.

“This is an important safety update from Pacific Gas and Electric Company. Weather conditions have improved in your area, and we are not planning to turn off electricity for safety in the area of your address.”

—2 p.m. Nov. 8, 2018

PG&E wouldn’t comment on its decision. The CPUC would say only that it is investigating when asked if the state was looking at why the utility didn’t initiate a blackout.