Content warning: This story contains discussions of suicide and suicidal ideation, If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of self-harm or suicide, know that you are not alone and that help is available by dialing the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 9-8-8.

Nahshon Garrett’s earliest memory of wrestling is forever etched in his mind. He was just four or five years old, visiting his grandmother’s small apartment on Shasta Avenue in Chico. In the cramped living room, with little sunlight peeking through the window, Nahshon’s father, Alvin Garrett, initiated an impromptu wrestling lesson.

“I think he was just excited to teach me something, so he asked, ‘You want to learn to wrestle?’” recalled Garrett, who graduated from Chico High in 2011 before competing at Cornell University. His father—who battled his own demons throughout his life and rarely visited his son due to his frequent stints in prison—was eager to share what he knew during their limited time together. “I said, ‘Yeah! I want to!’ It was short-lived, but I remember it as clear as day. It was the first time I ever got to be excited with my dad about something.”

That fleeting moment of connection through wrestling would prove deeply significant for Garrett, whose eventual accomplishments in the sport include two California high school state championships; a Division I NCAA title; a place on the 2018 U.S. World Team; and an invitation to the 2024 U.S. Olympic trials this past April. Additionally, the Chico native was a four-time NCAA All-American; a four-time All-Ivy Team Member; and was twice named the Ivy League Wrestler of the Year. More important to Garrett though is the role the sport has played as an enduring link between father and son, a shared interest that transcended Alvin’s personal struggles.

When Garrett was just 11 years old, his father succumbed to cancer, magnifying an absence that Garrett had always felt, but hoped would be remedied. With Alvin’s passing, that void became final, but the seeds of resilience and passion had been planted, seeds that would be tended by a supportive mother as well as high-school wrestling coach whose similar life story would lead to a bond that helped both men grow.

Reflecting on his father, Garrett described him as “a troubled man who tried to fight his past—his trauma. I think he was a troubled man who was overcome by the pain of life, who had experienced some of the worst things that could happen to children and men.” Despite the hardships his father faced, Garrett believes that in the handful of smaller moments they shared together, his father saw hope and a reflection of himself in his children, wishing that they would choose a path different from his own.

With every step onto the wrestling mat after his dad’s passing, Garrett grappled not only with his opponents but also with the shadow of his father’s past. Each match and practice became a tribute to the man who first showed him the ropes, a way to nurture and preserve the core memory of their shared passion while simultaneously confronting the realities of his dad’s life.

“I was in seventh grade and was in my history class,” Garrett recalled of the day his father passed. “My brother walked in and said, ‘Hey, we got to go.’ He told me straight. We knew he was dying. They released [my father] from jail because he was on his way out. He knew we were there with him. I don’t necessarily recall his last words, but what I remember is his sense of peace. It was finally time to have some peace and rest.”

With wrestling, Garrett found an anchor amid the turbulence of adolescence, a vehicle for coping with trauma and carving his own path while keeping his father’s memory alive. The sport became a battleground where Garrett could confront and ultimately overcome the shadow of his father, process pain and forge his own identity in the process.

Through middle school and into high school, Garrett’s commitment to the sport grew, and his talent began to shine through as he leaned heavily on the support of his mother, Golden Sizemore.

Sizemore embodied the resilience and strength that would eventually shape her son’s character both on and off the wrestling mat. “She laid the foundation and the groundwork for my morality,” Garrett reflected. “And I would say just the very fabric and nature of how I want to be presented to people. She’s a very kind, very humble, smart woman. She’s very secure and stable in herself. And that’s what I saw growing up.

“Her dedication to the service of others, and a dedication to God, that aspect of essence outside of herself was beyond anything I could have seen around school. And so that’s what she offered me,” Garrett continued. “She … overcame her own struggles, overcame her own desires, her own tendencies, her own habits, her own traumas, her own struggles to fight for us in the most pivotal part of our lives.”

This fight, as Garrett described, was not just about custody or advocating for him at a formative time in his life. It was a battle against the shadows of their experiences and traumas, the pain Sizemore had endured through failed marriages, the abuse of husbands, and the addiction she had to overcome. “These are the things that we fight against, you know, and when it mattered, … [in the] most important times in my life, I was under her shelter.”

Even with his mother’s crucial presence, the absence of a father lingered, and Garrett often found himself longing for male guidance.

Keith Rollins was Garrett’s wrestling coach at Chico High, and he understood the transformative power of the sport firsthand. He also knew the pain of losing a father at a young age. Growing up in the small town of Avon, Minn., Rollins’ life was forever changed when, at the age of 18, he discovered his father’s lifeless body in the woods, a victim of suicide.

Photo courtesy of Meghan Rollins

“It was a wooded area. I saw my dad laying on the ground,” Rollins shared, his voice heavy with the gravity of the memory. “I started freaking out. Everything became a blur. They had to restrain me and put me in the cop car.”

His father had suffered a mental break, and the tragic loss sent Rollins into a downward spiral of destructive behavior, depression, and suicidal ideation as he grappled with the complexities of grief and trauma. “I was constantly in a very, very bad place,” he admitted. His once comfortable hometown now felt suffocating, every corner holding painful reminders of his dad and the stigma surrounding his death.

But in this dark time, wrestling became Rollins’ salvation. The sport gave him an outlet to channel his pain and rage. “I could go to a wrestling practice, get super physical … and the violence would take some of that pain away.” Through wrestling, he began to slowly transform his life and heal, even as he carried the scars of losing his father.

Rollins struggled in the aftermath with constantly shifting feelings related to his father’s death, and said, “It would change. I would be mad at him, mad at myself—’Why didn’t I do more?’ It was a constant pain that’s really hard to find answers when someone chooses to leave the world.”

Despite the solace he found in the sport, he knew he needed to escape the small-town gossip and pitying looks that followed him in Avon. Leaving Minnesota became a necessity, a chance to start fresh and build a new life.

Desperate to shed the weight of the past, Rollins saw California as a blank slate, and he moved to the Chico area in 1994. He got his start locally as a wrestling coach at Durham High School before moving on to Chico High School, where he currently teaches Special Education classes in addition to coaching.

He would go on to become a highly acclaimed coach at Chico High—earning the titles of 2008 Northern Section Coach of the Year and 2022-23 NFHS California Wrestling Coach of the Year. He drew upon his own experiences to guide and mentor young wrestlers, understanding intimately the profound impact the sport could have on a person’s life.

He quickly recognized himself in certain athletes—kids from broken homes, grappling with trauma and self-doubt. Garrett was one of those kids. Reserved but immensely talented, Garrett found in Rollins not just a coach, but a mentor and father figure.

“Other than my mom, he’s the only other person in my life that I truly felt safe with,” Garrett said of Rollins. “He was there. He never pushed me away.”

Rollins saw in Garrett a reflection of his own struggles and triumphs. He understood the young wrestler’s need for stability, encouragement, and tough love. “I want to make an impact,” He said of his coaching philosophy. “I want to be a part of their life. I want to help them.”

On and off the mat, Rollins was a constant presence in Garrett’s life. He drove him to practices and tournaments, spent countless hours coaching him through moves and mindset. When Garrett’s anxiety or self-doubt crept in, Rollins was there to talk him through it.

One pivotal moment came at the Five Counties tournament during Garrett’s junior year. In a heart-to-heart before the finals, Rollins shared for the first time that his father hadn’t died of Lyme disease as he’d previously said. He had taken his own life. “It was the first time he became human to me,” Garrett remembered.

That vulnerability, that shared understanding of loss and pain, only deepened their bond. Garrett went on to win the state championship that year, the first of many triumphs. But the real victory was in the healing and growth that wrestling facilitated.

The trauma in his life took a heavy toll on Rollins’ mental health. “I started having panic attacks. I started having extreme depression and anxiety where I couldn’t get out of bed,” he shared. “There were just so many things, probably about seven or eight years where I was completely self-destructive. There was just no happiness in my mind—there was zero.

Ultimately, he came to recognize the importance of dealing with grief head-on. “I think had I been very open and honest and dealt with the death of my father in a way that I confronted it, I don’t think I would have had the struggles I have,” Keith admitted. “I see that now.”

Rollins said that during his father’s difficult years, no one was aware of his struggles: “He wasn’t willing to seek counseling or medication.” Learning from his father’s experience, he made a commitment to himself, saying, “Anytime I’m struggling I’m going to turn to people and ask for help,” rather than suffer in silence.

A month before his father’s suicide, Rollins suffered a devastating loss at the Minnesota state wrestling tournament. It was his junior year. After winning his first match, losing the second, and battling back for a chance to place, he lost the final match. He had poured his heart and soul into the tournament and left without making the podium.

“I was just devastated afterward,” he remembered. “I didn’t want to be around anyone.”

But in that moment of despair, his father found him. He had left the stands, searched the locker room, and pulled Rollins into a hug. “He told me how proud he was of me—that it didn’t matter if I was on the podium or not,” Rollins recalled. “Looking my dad in the eyes at that moment meant a lot. It was one of my last memories of my dad. One of my best.”

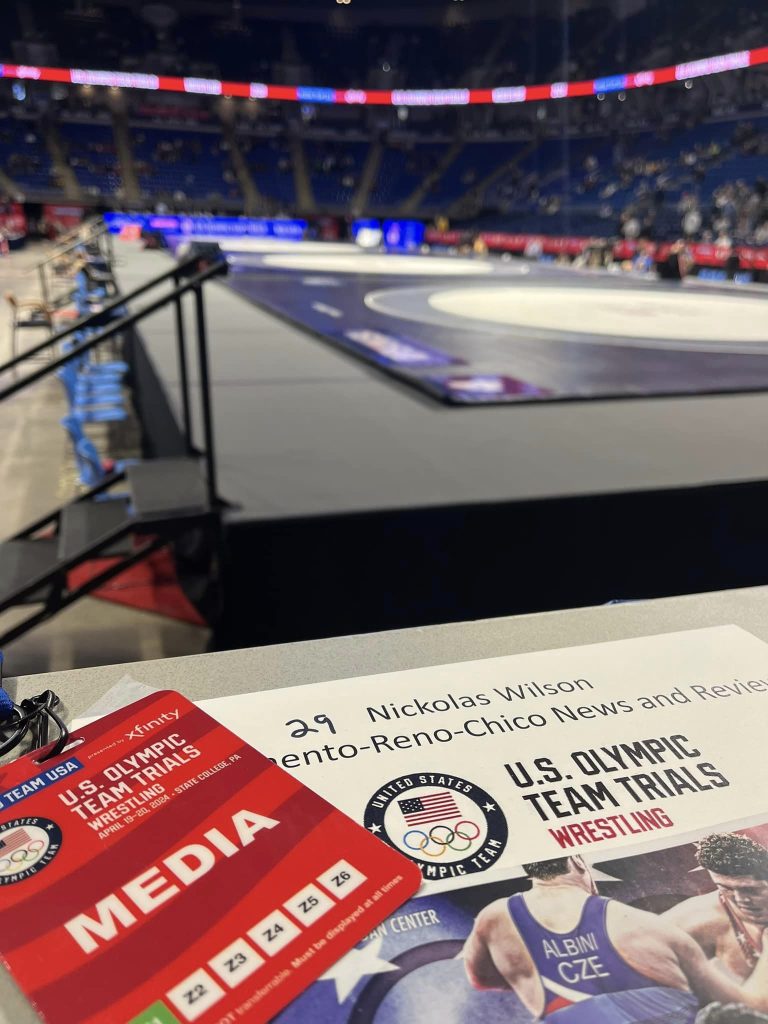

Photo by Nick Wilson

The memory supplied Rollins with a flicker of hope that sustained him during the intermittent periods of anger, grief, and confusion that followed his father’s death. The unshakable affection the son felt in that moment became a cornerstone of his coaching, guiding him to prioritize all-encompassing support and encouragement for his athletes, regardless of their performance outcomes.

Coaching became a way of processing his own grief and trauma while providing guidance to those facing similar struggles. “Serving kids—going through what I went through, just the desire to let people know that they’re not alone, that there is someone who cares and wants the best for them. I embrace that role,” he said. “I’ve always had this desire to help others, it’s always been something that’s really important for me—especially kids. It just feels almost like a healing thing for me to be able to help someone who lost someone, lost their father, whatever it is.”.

He recognized that for kids like Garrett, wrestling was a way to find control and self-worth amid chaos. “Nobody can take those couple hours in practice away from you. … This is something you can own.” Through coaching, Rollins found a sense of purpose and healing in helping others navigate the challenges he had faced himself. “The impact I have on others far outweighs any accolades,” he emphasizes.

Both men have come to a place of forgiveness and acceptance around their fathers. “I think he saw hope in us,” Garrett said of his dad. “That in some ways, he hoped we wouldn’t be like him. No matter how bad things were, I do think he really loved us.”

Though the pain of loss still lingers, Rollins’ perspective has shifted. “I’m not angry at my dad anymore. I hold onto amazing memories of my dad. He was really a good father but suffered from mental illness.”

As a coach and now father himself, Rollins is committed to being the mentor he wished he’d had. For every kid that steps into his wrestling room, he aims to provide that same safety, encouragement, and unconditional support that helped Garrett feel a sense of connection that ultimately facilitated his accomplishments.

In the moments before Garrett’s first state championship match, as the arena buzzed with anticipation, Rollins pulled his young protégé aside, away from the glaring lights and the roar of the capacity crowd. In the quiet of that moment, he looked Garrett in the eye and told him that, regardless of the outcome, he was proud of the man he had become. It was a powerful gesture of uncompromising love and support, one that echoed the words Rollins had once heard from his own father.

In each other, and in the young lives they continue to impact, both men found the most profound victory of all: The power to shape a different ending to the story.

So proud of these men! Keith as my grandson- in- law and friend and Nahshon as a friend. The impact they’ve had on the young men they’ve met along their travels is unforgettable. Love you both so much! God bless y’all!💕💕

Thank you for sharing these stories. So proud if the Chico cos hes💖

Both of these men are champions on and off the mat! Humble and caring, true champions of life!

So much to learn from and admire about this story. Keith Rollins is a gem.

Thanks for sharing the real heart of this inspiring story.

My baby Brother Nahshon❤️ You are OUR Hero. Dad would be proud 🥲