In A Life for a Kiss, a 13-minute western made in 1912, a lone bandit with a posse on his trail takes a brief detour to get a drink of water at a small tree-shaded ranch house. On impulse, he steals a very forceful kiss from the woman who gives him the water, then rides away again. The woman (played by Pauline Bush) realizes her bold visitor is a wanted man, goes out to where her husband (early cowboy star J. Warren Kerrigan) is working on the ranch and tells him what has happened.

The husband immediately saddles up and goes off to join the pursuit of the bandit. They soon cross paths, and a lengthy chase ensues. The posse stops briefly at the ranch, and the woman joins the pursuit. After much gunfire and a cliff-hanger style brawl, the bandit (played by the formidable Jack Richardson) is close to killing the wounded husband, but the woman and the posse arrive just in time for her to bring down the bandit with a single shot.

As such, A Life for a Kiss unavoidably sounds old-fashioned and merely conventional, but watching this restored film on the Eye film museum’s YouTube channel shows it to be a surprising and surprisingly satisfying piece of early movie storytelling. The narrative is conventional, but the conventions are scrambled in interesting ways. Kerrigan’s “good guy” has top billing, but it’s Bush’s female lead who rides to the rescue. And the bandit is the character we see first, and most often, in the film’s brief, unrushed running time. And he’s also in the film’s haunting, oddly angled final shot, with members of the posse crawling toward his corpse on that very steep hill.

Bush’s ranchwoman has the “hero” role here, but Richardson’s bandit is arguably the central character in this small, swaggeringly off-handed tall tale. His passionate recklessness sparks the action and gives a touch of romantic outlaw balladry to the entire proceedings. (Think about that title: A “life for a kiss,” anyone?) Early on, he waits for the posse to get close enough for him to wave in defiance before galloping away. Later on, in the chase sequences with Kerrigan, he slows down at times and even stops, as if daring his pursuer to fight face to face. This villain is a bad guy who seems to know that his goose is cooked. We aren’t party to his life story, but we do get the sense that he’s determined to go out with a flourish.

Director Allan Dwan, whose filmmaking career would ultimately span a half century, stages those chase sequences on curved hillside trails and roads. The camera remains stationary as the riders rush past and into the distance or, less often, as they emerge in the distance and swirl down toward the camera. Those long, patiently composed shots observe the surging action but maintain an impassive distance from it, rather as if to give precedence to the rough, glowing landscape over the furies of humans and horses. The results make for a rich mixture of the pastoral and the epic.

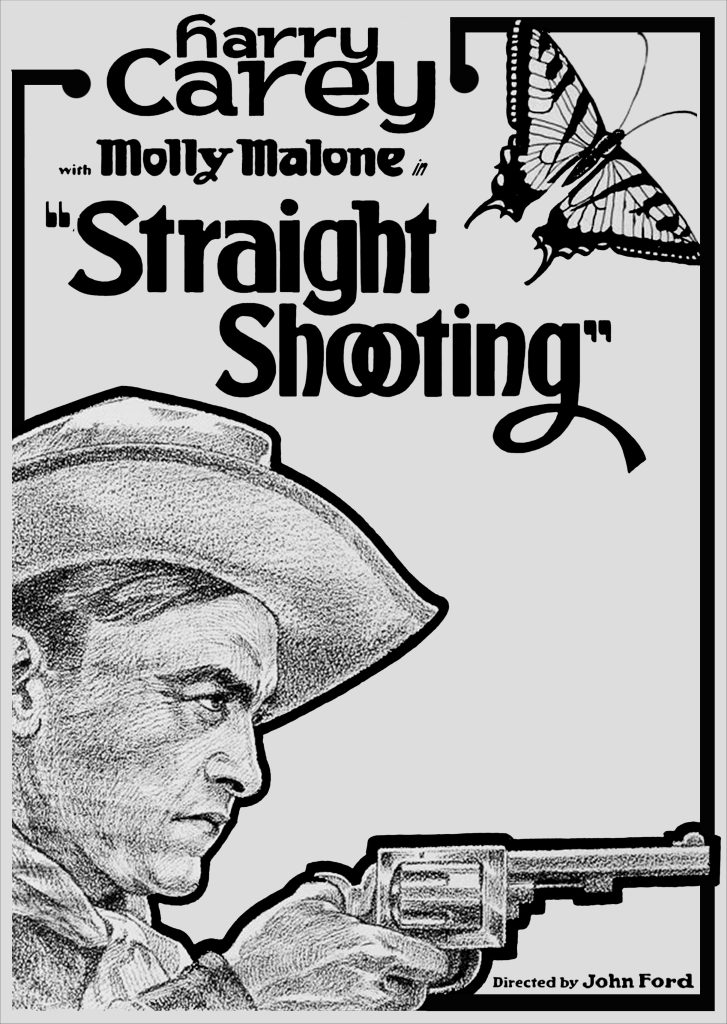

One of the great pleasures of “streaming in place” has very much to do with an abundance of opportunities to visit and explore early cinema treasures like A Life for a Kiss. It’s in that spirit that I’d recommend online visits to the film collections of the Library of Congress and the Eye film museum, and video visits to such beautifully restored silent westerns as William F. Haddock’s In the Tall Grass Country (1910), William Nigh’s Salomy Jane (1914), John Ford’s Straight Shooting (1917), Ruth Ann Baldwin’s ’49-’17 (1917), Dwan’s Tide of Empire (1929), and two with Buck Jones in country-boy roles—Ford’s Just Pals (1920) and Frank Borzage’s Lazybones (1925), etc.

Be the first to comment