Some leaders are discussing building on the city’s protected rural western border

By Ken Magri

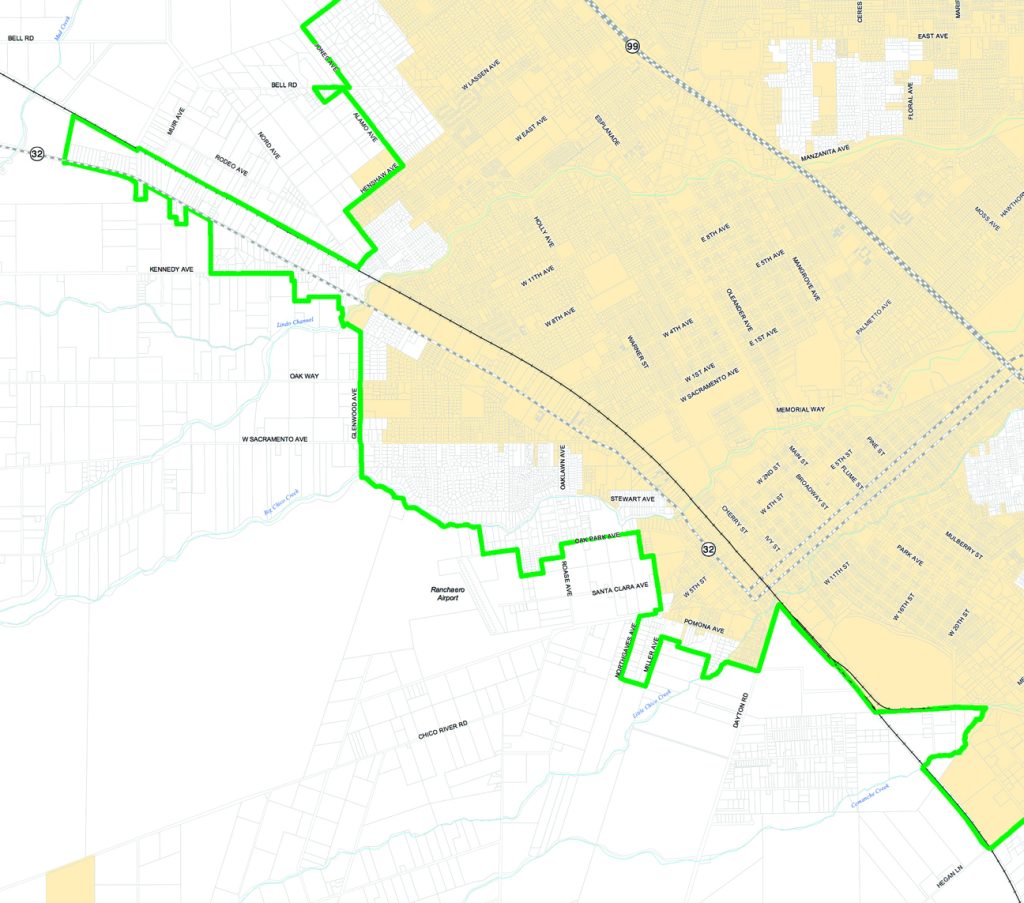

On January 14, the city council’s Growth and Community Development Committee met to discuss whether Chico’s western border, called the Greenline, needs to be expanded in order to meet state-required goals for new housing. Chico City councilmembers Tom Van Overbeek and Addison Winslow co-chair this sub-committee, which was created last June.

Chico’s Greenline, established in 1982 by the Butte County Board of Supervisors, protects essential farmlands on the western border from being eaten up by urban expansion, sometimes called “urban sprawl.” The original plan was slightly modified afterwards, but has otherwise been successful in holding steady while the city grows in other directions.

The meeting was so contentious, however, that one member resigned.

Pam Figge was the member who walked away. She’s a veteran land-use planner with over 40 years of experience, working in Gridley, Paradise and Chico. Figge cited her stress about trying to do good work while operating “in the political arena” where consensus was increasingly difficult to achieve.

At the meeting, committee member Jim Stevens, a principal of Northstar Engineering, presented a set of facts suggesting that additional growth on Chico’s eastern and northern sides is so problematic that it’s unfeasible. In their response, some committee members suggested that the city may need to build on the western side of town, advocating for expansion.

Others argued for more infill housing (homes built on available empty lots) and greater housing density, measured as “units-per-acre,” in future projects. Committee member Ann Bykerk-Kauffman and housing advocate Marty Dunlap made a visual presentation about the current state of affordability for prospective Chico home buyers.

Still others wanted to bring back large, previous housing projects like Valley’s Edge on the southeast side, which was voted down in a 2024 referendum.

These different positions add up to a complicated and difficult set of questions. Where should Chico expand and how dense and affordable should its housing be?

Some statistics and housing history to consider

Housing is considered affordable when the household pays no more than 30% of gross income for housing costs, including utilities, according the US Department Housing and Urban Development, or HUD.

In Chico, the annual median (or mid-point) wage for households is $61,464. But the current median sale price for a single-family house is $466,000, according to redfin.com. That means about half of Chico’s households could afford that mid-range $466,000 house, but only with a 20% down payment at a 3.0% interest rate. At this time, however, a 30-year fixed mortgage interest rate is 6.95%. This would only afford the median income household a home priced between $250,000 and $280,000. To be more specific by example, it would buy a two bedroom, one bathroom house with 715 square feet on 23rd Street, on a 0.06 acre lot in the Chapmantown neighborhood, currently listed on Zillow.com for $264,000.

Yet Chico keeps building a disproportionate number of larger single-family homes that are only affordable to buyers earning above that median-income.

In 2015, the City of Chico set a goal for itself to develop a range of “mixed income/inclusionary zoning options for council consideration.” This concept required developers to include “a percentage of low-income affordable homes” as a part of their more expensive housing projects.

But is zero considered “a percentage?”

On page 428 of Chico’s 465-page Housing Element master plan, the city actually admitted in 2023 that the objective was not met nor even attempted.

“The City Council has not been interested in pursuing an Inclusionary Zoning ordinance” was the report’s brief explanation.

What is “missing middle housing” and could it help?

Missing middle housing refers to duplexes, four-plexes, townhouses and other types of multi-family living structures. The term was coined in 2010 by Dan Parolek, a Berkeley-based architect and co-founder of Opticos Design.

Once common in the years before World War II, this type of housing was more affordable and could accommodate more people on a single parcel of land. Middle housing is considered missing “because such building types were often made illegal or difficult to build” under local zoning laws, according to the National League of Cities.

To blend in with existing neighborhoods, Parolek said multi-unit structures can be built at “house scale,” meaning that their height, width and depth are similar in size to single-family housing, “even though there are multiple units inside.”

Middle housing can increase the housing density of a single acre to achieve the 16 units necessary to support small commercial and service amenities and mass transit.

A large part of this strategy also includes adding onto existing homes with room additions, garage conversions and Accessory Dwelling Units, ADUs, which are small homes built in backyards. Chico is championing ADU support. The city offers a variety of pre-approved designs that cut down development costs.

Likewise, California Senate Bill 9, which went into effect in 2022, allows eligible single-family homeowners to split their lots and build up to two homes, at least 800-square-feet each, on both parcels, creating four units where there was once one.

Besides ADUs and parcel-splitting, is there enough available infill land in Chico to make middle housing work? Or should more of it be incorporated into future large scale developments?

While she’s no longer on the committee, Pam Figge told the News & Review that “the Chico General Plan and consistent zoning regulations allow for the development of middle housing. The issue is why aren’t developers building that type of housing?”

Figge added, “I asked this several times at the committee meetings.”

Committee member Douglas Gullion answered Figge’s question for CN&R with a vague statement that claimed “existing housing is middle housing.”

Gullion, a real estate developer who was involved with the Valley’s Edge housing plan, is also a Growth and Community Development Committee member.

“That [middle housing] market is being addressed, but the market with the most demand is not,” Gullion asserted. “The 3 bedroom/2 bathroom single-family detached house is being opposed by special interest activists and obstructionists.”

Committee member and housing advocate Eric Nilsson disagrees.

“Data from [Chico’s] Housing Element shows that we have built far more 3/2’s over the last ten years than what was recommended in the Housing Element,” Nilsson observed.

Which is the right direction for Chico’s expansion?

In 1988, a proposed development called Rancho Arroyo wanted to build 3,000 units on 788 acres in Chico’s northeast corner, near the entrance of Upper Bidwell Park. It was defeated by voters in a referendum.

A smaller follow-up proposal on the same site, called Bidwell Ranch, was opposed and also never built.

The city ended up purchasing that property as a natural fire-break and is preserving it to offset carbon requirements if the nearby airport is expanded.

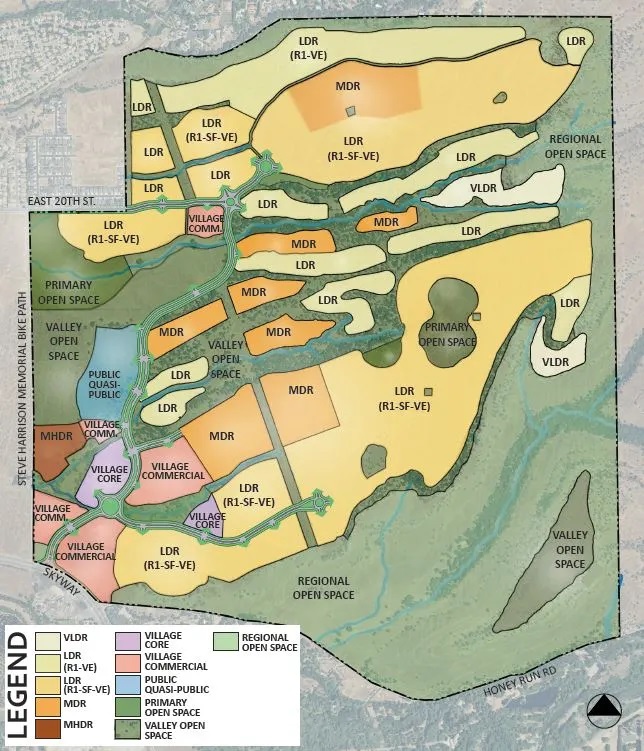

Last spring, Chico voters also defeated the Valley’s Edge proposed mixed-use housing community of 2,777 units on 1,447 acres designated for the southeast corner of town.

“People began to realize … that this was a development for a small minority of people, mostly buyers outside of Chico who could afford the expensive homes,” Eric Nilsson told ChicoSol in an article after the 2024 vote.

But Bill Brouhard, one of the landowners and a principal in the Valley’s Edge project, disagrees.

“The idea of densifying the urban core and articulating how it is being densified, the original plan had it,” Brouhard told the News & Review. “But we didn’t articulate it in a way that was understandable, and that was our mistake.”

Councilmember Addison Winslow countered that “over 80% of the residential land in the Valley’s Edge plan was dedicated to low-density.”

Both Brouhard and Winslow were right: Valley’s Edge did have 40% medium and medium-high density housing units, beautifully designed to fit in with nature-scaping near commercial units located in the front.

Brouhard estimated that the smallest unit type, a 640-square-foot one bed/one bath all electric home with solar and a covered lanai but no garage, would have been priced at around $299,000. The “Type B” 2 bed/2 bath versions were estimated to sell for $339,000.

But 60% of Valley’s Edge (not 80%) was in fact more expensive single family homes on individual lots, labeled “low” and “very low” density. There was such a lack of density that it brought the whole Valley’s Edge average number of units-per-acre down to 4.7.

That is slightly over half of what housing experts consider appropriate for any smart growth.

On the subject of Valley Edge’s density, or lack thereof, Winslow noted, “We only have so much land appropriate to build on, and sprawl comes with serious environmental and financial costs.”

CN&R asked Winslow to name any recent housing projects that meet his calculus of affordability, density and access to mass transit and services.

“The Foundation on Park Avenue is probably the best situated affordable housing project post-Camp Fire,” Winslow responded. “Creekside Place near Meriam Park and North Creek Crossings in Meriam Park are also in lovely and walkable areas. “Doe Mill on the other side of Bruce Road; all great examples of mixed-housing with good street design.”

Winslow further elaborated, “When I say ‘good urban development,’ I mean what the Sacramento General Plan says: walkable, mixed-use, diverse to match the diversity of the population … Street design is an important component.”

Finally, the whole committee is asked about expanding the Greenline

Committee Co-chair councilmember Tom Van Overbeek said yes, the Greenline should be modified.

“Some parts of the Greenline are only one mile from Downtown,” he told CN&R. “Some newer building is going on four-plus miles from downtown.”

But Van Overbeek wants bipartisan support.

“If we want a compact urban form,” he went on, “it’s obvious we should look to the West, but carefully.”

Winslow disagrees about expanding that line for now.

“No, I don’t think so,” he answered. “But we may want to consider it someday … Planning is all about balance and, frankly, the balance Chico has had in 75 years of suburban sprawl has left us with overstretched, underfunded infrastructure chasing the dragon of affordability with a fundamentally unaffordable pattern of development.”

Former committee member Pam Figge was very clear.

“The Greenline protects the best class of agricultural soils,” she stressed. “We should not break the Greenline.”

Figge explained that Butte County already allows for some residential development to occur on these rich soils, mentioning this “really meets the definition of sprawl – large lot, mono use (single-family residential), auto-oriented with little or no services.”

She added, “This is why the City of Chico decided in the 1990s that we would accommodate growth to the east where the soils are not suitable for agriculture.”

While an attendee, but not on the committee, Bill Brouhard agrees with Figge and Winslow about not expanding the Greenline.

“We should be building houses where food doesn’t grow,” Brouhard acknowledged. “I committed all of my development and expertise on the east side of Chico because I support the Greenline.”

CN&R asked Brouhard if he would support a scaled-down version of his own Valley’s Edge project at the same location, but with more housing density per-acre. He answered ‘yes,’ in theory, though emphasized that it was “too early to tell” about personally spearheading such an effort.

“I like the idea of spreading density into traditionally single-family neighborhoods,” Brouhard remarked, “but, again, that has to be laid out physically in a way that makes sense.”

Committee member Bykerk-Kauffman had three crucial conditions before supporting an expansion of the Greenline.

“I would only consider expanding it after the city has (1) taken all the steps it can to make ‘missing middle’ housing easier to build, (2) let those steps take effect for several years, and then (3) found that there is still insufficient housing to meet the needs of our residents,” Bykerk-Kauffman replied.

Doug Guillon deferred on the Greenline, saying it was too early to be asking that question.

“The location of Greenline modifications will be studied extensively and supported by studies, public/private sector input, with land use expert’s overview,” Guillon pointed out.

“At this point, I do not support expanding the Greenline,” said committee member Nilsson, who also felt the discussion was premature “given the fact that we have yet to determine an agreed upon set of data related to housing: inventory, current construction, approved projects, projected growth etc.”

After multiple attempts, the News & Review was unable to contact committee member Jim Stevens for a response.

Whatever happens in the future, this spearhead question about expanding the Greenline generates several other important housing concerns that Chico is failing to directly address. Perhaps the most urgent question of all is how to build a simple affordable place to live in Chico.

A point on a comment of mine: you report that I gave the amount of land in the Valley’s Edge plan wrong. You mistook percentage of housing units for percentage of land. 80% was the proportion of land dedicated to low-density.

Chico is no longer the small/big town I loved. In the ten years I have lived here I have watched orchards disappear and housing units after housing units being built. The traffic is now horrendous. It is almost impossible to find a parking place on the street. The small but amazing small feel of the town gone. I don’t understand Chico has to keep expanding and expanding. Where does it end?

Chico is losing its small town feel with population and traffic increase. I grew up in what became Silicone Valley and watched the orchards disappear. I’d prpbably fall under the obstructionist label. Not only agriculture but wilflife needs space.