By David Bacon

This story is produced by the award-winning journalism nonprofit Capital & Main, as part of its Ill Harvest series, and co-published here with permission.

For Maria Zavala’s family, there are no easy years. But last year brought the family to the edge of disaster. Zavala, a lettuce worker, is diabetic, and in addition to two other medicines she has to take regularly to control diabetes, she carries an insulin pen. Her 17-year-old son has attention deficit disorder, and she says his doctor told them his depression is one reason why his weight grew dangerously.

Then this year, her 15-year-old daughter also became seriously depressed. Zavala looked for a psychologist or therapist at the local clinic and hospital in Salinas. “There were no appointments,” she says, “and especially no one available who can treat adolescents.”

The Zavalas are covered by the health care plan from her union, the Robert F. Kennedy Farm Workers Medical Plan. It works fine for her everyday needs, she says. She pays $25 every time she fills a prescription, far below the over-the-counter price of the medicine her family needs. A doctor visit costs $25 for the first five visits and then goes down to $15.

But the closest treatment she could find for her daughter was from the Ohana Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health in Monterey, 20 miles away from their home in Salinas. Ohana is not part of the network of approved providers under the RFK plan, but she talked to the plan administrators and they agreed to provide coverage. Still, the co-pay was a hardship for the Zavalas. For the $4,000 bill, the plan paid $3,000. “A thousand dollars is still a lot for us,” she explains, “but it’s much better than $4,000.”

The RFK plan covers about 3,000 members of the United Farm Workers — about 7,500 people, counting spouses and children. “While that’s a small percentage of the state’s estimated 700,000 agricultural laborers,” according to plan administrator Patrick Pine, “it sets a high standard even for state policymakers and other growers.” In 2015, the Affordable Care Act mandated that all employers with more than 50 full-time workers offer medical coverage.

People who work in the fields, however, are usually faced with plans that cover very little, with premiums that are often prohibitively expensive, according to Lauro Barajas, a regional director for the United Farm Workers. The RFK plan may not cover everything with no co-pays, but it gives farmworkers the kind of coverage that’s familiar to union workers in urban jobs that often pay much higher wages. According to Farmworker Justice, campesino families still have annual incomes that average $25,000 to $29,999 nationally.

While the RFK plan provided the basic medical care for the Zavalas at a cost they could afford, Maria’s situation became more perilous this spring. For reasons she never understood, the clinic she uses in Salinas, the Santa Lucia Medical Group, began saying the plan would not cover her diabetes medication. “I talked to Edgar [her union representative], and he talked with the plan,” she says. The plan administrators were able to straighten the pharmacy out, but it took two months, and in the meantime her medicine ran out.

“The pain was bad,” she remembers, “but I tried to just live with it because going to the hospital would be expensive. But then I couldn’t urinate anymore, and it got so bad that one night I asked my husband to take me to the emergency room.” When she got out, that was another bill. The plan paid $1,600, and she paid $700. “The reality is that we depend completely on our plan,” she emphasizes. “Without it, I don’t know what we’d do.”

That is the prospect that faces them now. Zavala works for the D’Arrigo Brothers Company, one of the largest growers in the Salinas Valley. She has medical coverage because it is negotiated in the contract D’Arrigo has with the United Farm Workers. The company pays the entire premium, but in order to qualify for coverage, she has to work about 80 hours a month. She can do that from May to November, but it leaves four months in the winter when she has to pay the premium herself.

Her husband also works, but at another company with a health plan that’s much more expensive and covers much less. He supervises a crew of contract workers on agricultural visas, and for months he’s on the road, only coming back on weekends to see Maria and the children. Still, they are all covered by RFK. So, between his job and her savings, they have been able to make it. They even bought a modest house in Salinas, where a large print of the Last Supper hangs proudly on the wall of her spotless living room. The mortgage is $2,300.

Every year, she saves about $4,000, from a monthly wage that adds up to about $3,000. That’s what she uses to keep her insurance in the winter. But she expects the plan’s cost to increase in 2023. Her hospital visit and her daughter’s care have already wiped out her savings, and the twice-weekly visits to Ohana will continue to cost a lot. Jobs in any farmworker town like Salinas are hard to find until work picks up again in the spring. As she listed the bills she feared she wouldn’t be able to pay, she began to cry. “It’s going to be very hard. I don’t know what we’ll do, but we have to keep our insurance. My back is to the wall,” she says.

Origin of the RFK Plan

The idea for a farmworker medical plan came out of the grape strike that started in Delano in 1965. The vice principal of Garces Memorial High School in Bakersfield, LeRoy Chatfield, went to work for what became the United Farm Workers in the strike’s first year, at a salary of $20 a month.

Chatfield then explained to his Catholic superiors that Cesar Chavez had put him in charge of developing a plan for farmworker cooperatives. “Our idea,” he told them, “is to build a complex of cooperatives (clinic, pharmacy, credit union, garage, etc.) somewhere in the valley … owned and controlled by farmworkers themselves.” The union’s first effort in health care was setting up a clinic at its Forty Acres headquarters in Delano. That was followed in subsequent years by clinics in Salinas and Coachella. “We look upon this as a prerequisite for serious grassroots organizing,” he wrote.

Chatfield was put in charge of recruiting doctors, nurses and other health professionals to staff them. “The clinics were important because prior to them, there really wasn’t a place farmworkers could go to get good medical care,” recalls Arturo Rodriguez, who was UFW president from Chavez’s death in 1993 until 2018, when Rodriguez retired. “They’d end up in emergency rooms, and there were all kinds of horror stories. What little care they got cost an exorbitant amount of money. And because farmworkers had no access, they were susceptible to all kinds of illnesses.”

The clinics were not just service providers, however. They were the means to show workers that their collective action could create change. “They demonstrated to workers and their families,” Rodriguez says, “that the union was trying to deal not just with low wages and bad treatment in the fields, but with the needs of families outside of work. We were saying, this is what the union can do, providing things they never got before from employers, labor contractors or the government. It gave workers a reason to take the risks we were asking to bring in the union.”

The Coachella clinic was inaugurated with a march through the valley at the beginning of union representation elections in 1976. In the 1980s, the union established one final clinic in Salinas, but the clinics had become difficult to sustain. “In the ’60s and ’70s, a lot of doctors and nurses wanted to volunteer and spend time in programs that required work in rural communities, serving their needs,” Rodriguez explains. “That changed, and we could find fewer and fewer every year who wanted to live in places like Salinas and Coachella. Once we accepted that setting up clinics was no longer possible, we began working extremely hard on a medical plan that could provide the services workers and families needed at a low cost.”

Chatfield had been charged by Chavez with setting up such a plan, and by 1975 it had begun to be included in the negotiation of union contracts. Chavez would meet with the ranch committees, which were elected to represent workers at union companies. “Last night at the Perelli-Minetti winery meeting,” Chatfield wrote in a journal he kept at the time, “the workers were shell-shocked about the benefits. One of the workers said, ‘A year ago, I had nothing, and now you ask me if I like these benefits? They’re great!’”

Changing the union’s emphasis from clinics to the RFK plan, however, also meant that instead of services available to all workers, the plan only covered those who were under union contracts — a much smaller group. For the larger workforce, the union organized political campaigns to improve conditions in general.

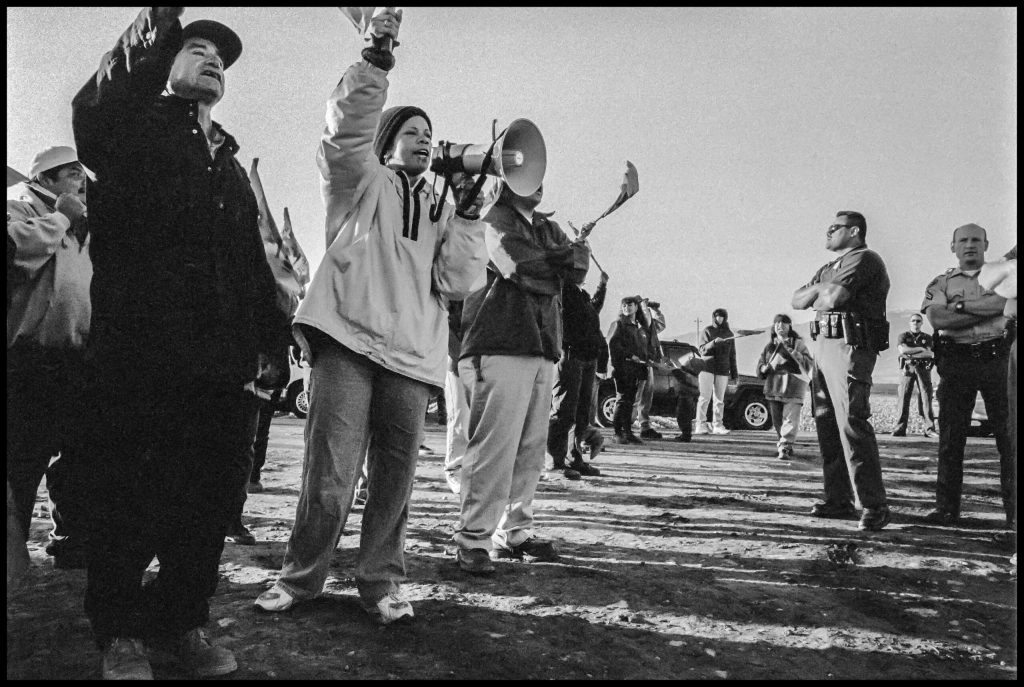

That included union campaigns in support of a suit by California Rural Legal Assistance to ban the short-handled hoe, which the state Supreme Court upheld in 1975. The use of the hoe contributed to spinal damage among workers who had to bend over when thinning vegetables and other crops over a period of years. Later, when cancer clusters were discovered in McFarland and other small towns in the southern San Joaquin Valley, the union launched a campaign against pesticide use on table grapes. And in 2005, after four workers collapsed and died in the summer’s extreme heat, the union successfully lobbied for an administrative rule establishing the right to shade and additional breaks in temperatures over 95 degrees, among other protections.

Until 2015, the D’Arrigo Brothers Company, one of the Salinas Valley’s oldest existing corporate vegetable growers and Maria Zavala’s employer, had a very contentious relationship with the United Farm Workers. The nascent United Farm Workers Organizing Committee signed a contract with D’Arrigo Brothers during the great Salinas lettuce strike of 1970. It lasted only two years and was not renewed. Workers voted for the union in 1976, but were unable to get an agreement.

Nevertheless, a core of union supporters worked for D’Arrigo Brothers through those decades. In 1998, another strike ended only when one of the company’s owners suddenly died. During negotiations in 2014, the D’Arrigo Brothers Company agreed to pay for the RFK plan, and the union signed a contract, which has been renewed. Under that contract, D’Arrigo has agreed to pay the entire premium for the RFK insurance plan, about $700 per employee per month this year. It includes vision and dental coverage and covers all immediate family members.

The plan is administered under the Taft-Hartley Act, with a board of three employer representatives and three union representatives. According to Patrick Pine, RFK plan administrator, “The challenge we face is that we cover workers in an industry with low pay, who live in markets like Salinas where the hospital and health care costs are some of the highest.”

Some California agricultural employers who have no UFW contract buy medical insurance through the Western Growers Assurance Trust or the United Agricultural Benefit Trust. For coverage similar to that of the RFK plan, however, Pine says growers pay premiums about 25 percent higher. According to Barajas, they usually pass most of it on to their employees by having them pay a large part for medical insurance with high co-pays and limited coverage.

Pine says the RFK plan keeps administrative costs below those of its competitors and doesn’t advertise or pay commissions to insurance brokers. Those savings result in lower premiums, according to Pine. “Our overhead is a lot less,” he says. “I get a much lower salary and work in [the UFW headquarters in] La Paz, where the cost of living is a lot less than in Los Angeles.” Rodriguez, one of the trustees, says the goal has always been “to maintain the lowest cost possible for employers and workers for a medical plan with the basic services workers use, including maternity, doctor visits and certain surgeries.”

To keep hospital costs low, John D’Arrigo, president of D’Arrigo Brothers, has contributed to Salinas’ Natividad Hospital, which launched the D’Arrigo Family Specialty Services clinic. Natividad has hired trilingual interpreters in Spanish, English and the indigenous languages spoken by many valley farmworkers, including Mixtec and Triqui. D’Arrigo promotes the Agricultural Leadership Council, which has 160 members and donated $4.1 million to buy equipment for the hospital.

Supporting long-term employment

A big part of D’Arrigo’s motivation is maintaining a stable workforce. “It’s hard to find workers today,” he said in an interview. “We have a shrinking, aging workforce. We have to take care of who we have and make our jobs attractive to the people who live here. We need a long-term workforce, and we want direct hires — people who work directly for the company.” At peak harvest season, D’Arrigo directly employs about 1,000 workers, and as a result the RFK plan covers about 2,500 people, including their families.

Maria Zavala may be a high-level user of plan benefits, but she is also a skilled worker, and the plan has kept her in the company’s workforce. For five years, she’s labored in the “corazones” crew, which cuts the lettuce for the company’s leading Andy Boy brand of packaged hearts of romaine. Her crew is mostly women, doing a job that 30 years ago was limited to men. Now just one or two men load the boxes onto trucks, and women do all the other work. Still, even with the union contract and health plan, D’Arrigo finds it hard to fill all the open seats on Zavala’s crew’s lettuce machine.

Hiring a labor contractor who provides the workers has helped fill in the gaps. Last year, workers with one contractor who brings crews from the Arizona/Sonora border petitioned to join the UFW so they could get covered by the RFK plan. “We worked with people in San Luis Rio Colorado to help put up a new hospital and meet the needs of the workers there also,” says Rodriguez, the plan trustee. More than 200 of those workers are now included under RFK. About 250 working for D’Arrigo with another contractor, however, are not. In addition, the company has increased its use of H-2A contract workers, recruited in Mexico on temporary visas. Those workers also are not included in the RFK plan.

“To me,” Zavala says, “RFK has functioned well. It would be great if it paid for everything, but compared to others, it’s much better.” When she had problems with getting her diabetes medication, she was able to use the union’s representative to complain and solve problems. Every year, D’Arrigo’s employee relations director, Marla Henry, visits each crew with Mercedes Martinez, the RFK plan’s assistant administrator. “If anyone expresses a concern, we get their name and contact information and investigate it,” Henry says. According to Rodriguez, “Workers have access to the plan’s administrators and do call the office to understand why they had to pay what they paid.”

“It’s not perfect,” Barajas concludes, “but RFK is a model for farmworkers. D’Arrigo and Monterey Mushrooms [large companies with UFW contracts], by offering the plan, are forcing their competitors to have better medical plans in order to attract workers. Every time we go into contract negotiations, those other employers are watching. They know that what we get is what they’ll have to pay, too.”

Be the first to comment