Windchime Park on Humboldt Avenue is known for many things. For starters, it has a giant wind chime created by former Chico artist Gregg Payne, which is why it is most commonly called Windchime rather than the official designation, Humboldt Neighborhood Park.

Among the unhoused community, it’s also sometimes called “Dog Park.” Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it has served as the location of one of the largest tent encampments in Chico. In 2020, the park was also the site protests and counter-protests of the syringe-distribution program that generated a viral spectacle of clowns, glittery butterfly wings and assault allegations.

Windchime Park was also the site of Chico Scrap Metal prior to its relocation to the site on E. 20th Street, where it remained in operation until Feb. 28 of this year. In striking resemblance to its current situation, the company was required to move from Humboldt due to operations being incompatible with the surrounding Chapman-Mulberry neighborhood, notably the low-income housing across the street.

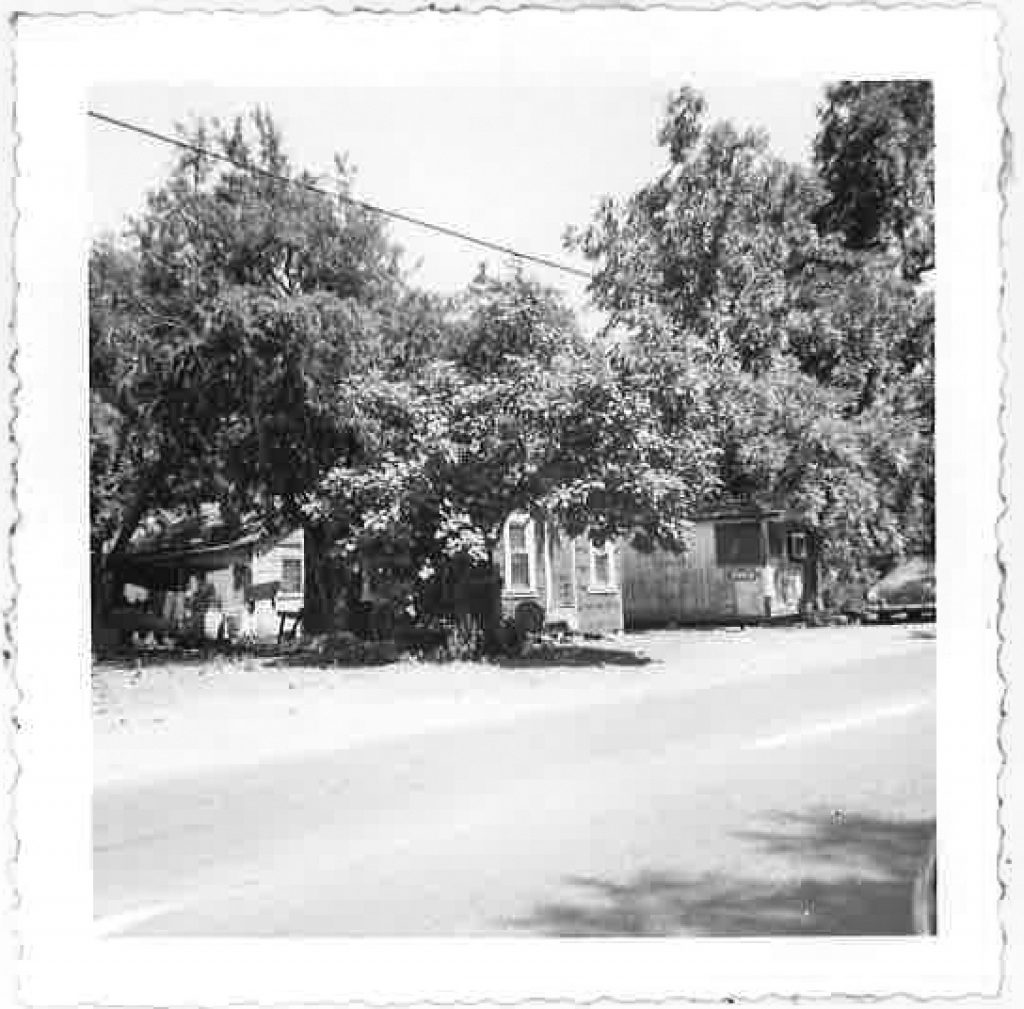

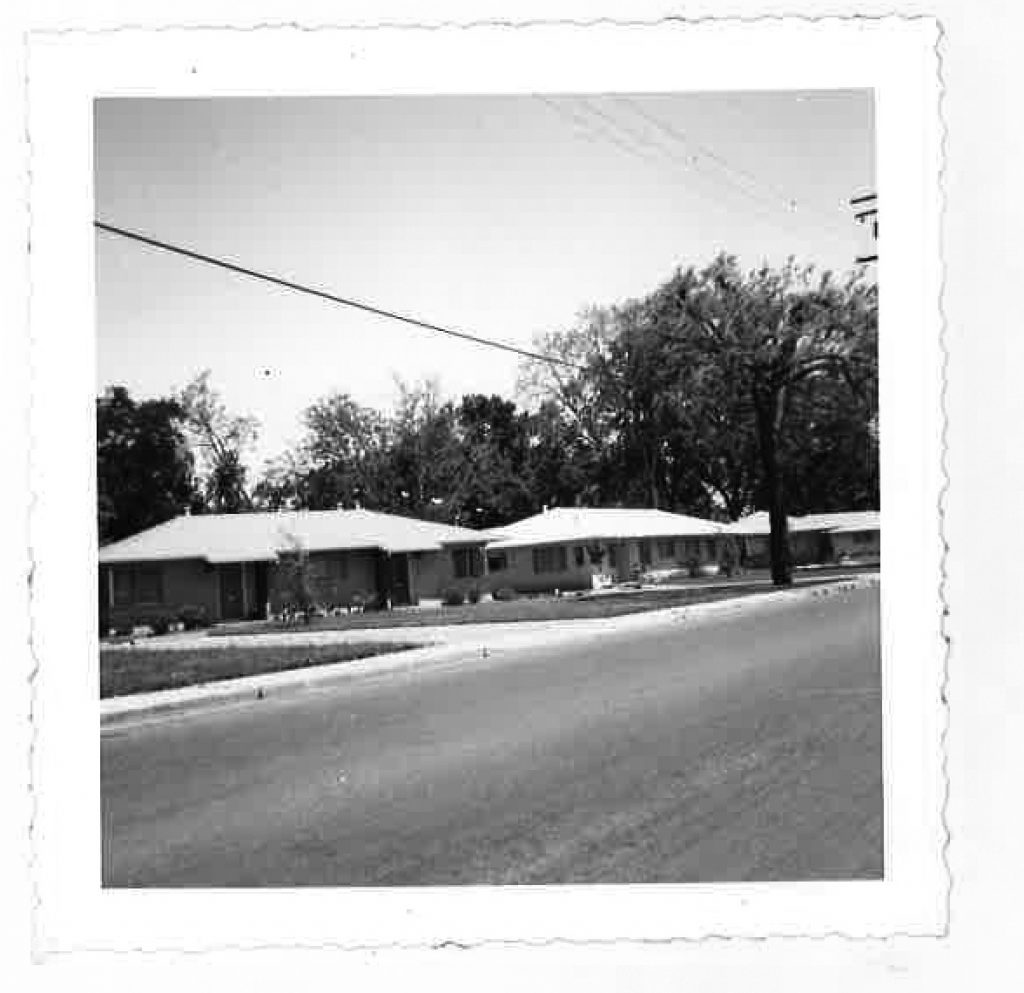

That low-income housing—a row of cinderblock duplexes facing Windchime Park— was part of Chico’s first public-housing project, its origin intertwined with hydrological engineering, municipal-housing politics and racism. The area was called Daisy Lane, and there is very little known about the place or the people who used to live there.

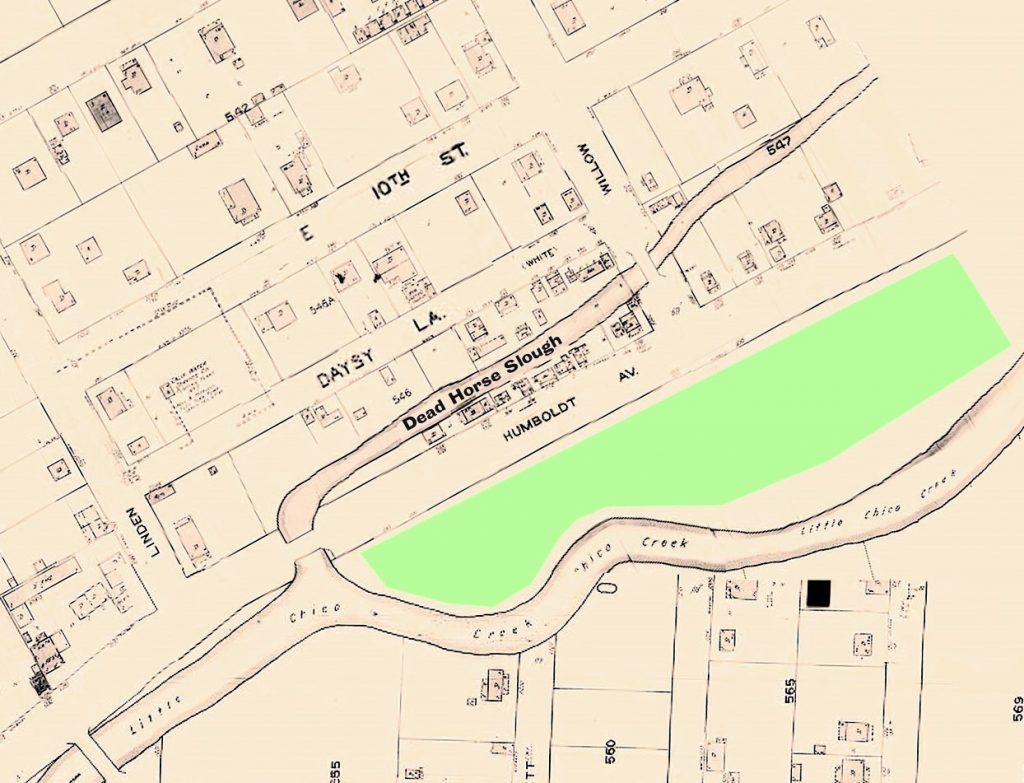

If you stand in the gravelly parking lot of Windchime Park and turn towards Little Chico Creek, you’ll see a great big cottonwood tree jutting out of the embankment. Examine the ground surrounding the trunk, and you’ll see a pebbly concrete fill where a stream once entered the creek. This is the original confluence of Little Chico Creek and its largest tributary, Dead Horse Slough.

Dead Horse Slough is a seasonal creek that runs out of the mountains just south of Big Chico Creek. It forms the gentle ravine where we now have Canyon Oaks Country Club, then is captured between a dam and a levee along Bruce Road to form the lakes of California Park.

Dead Horse Slough in the area in question—commonly known as Chapmantown—is of a humbler origin, as the name would suggest. Humboldt Avenue was the first highway into town from the foothills and, as with much of the city’s outskirts, it formed the setting of a lot of industry. The Big Chico Creek V-flume terminated at a sawmill yard east of Pine Street. A slaughterhouse located farther east served the cattle ranchers in the foothills, and butchers were known to use Little Chico Creek as waste disposal. The building where Has Beans roasts its coffee once hosted, by some (possibly apocryphal) accounts, the nastiest saloon in town.

After WWII, central Chico experienced urban decay. Like other U.S. cities during that era, affluent segments of the population moved to new suburbs and commuted by car while Chico’s downtown and core neighborhoods declined in wealth and population. Several of Chico’s largest buildings would be demolished before the end of the 1960s. So, Chapmantown was not the only of Chico’s neighborhoods plagued with under-maintenance and neglect at the time, but it did have a special reputation.

In 1957, sociologist Ritchie Lowry published a brief report called “Chapman Town: A Study of Substandard Housing.” Contrary to popular belief at the time, Chapmantown was only 9 percent nonwhite. However, around Daisy Lane (spelled “Daysy” Lane in some documents), all but two families on the block were African-American. This same block was singled out as the most utterly dilapidated. Lowry described the area as “entirely blighted: families living in decaying and rotting one room shacks, open privies shared by three or four families, no paved areas and so on.” Both the concentration of poverty and the condition of the dwellings can be connected to its location along the edge of a swale in an area that remains at high risk of flooding today.

Lowry’s work ignited support for public housing from the Chico City Council. Seven years earlier, the council had discussed accepting a round of projects, but their efforts were interrupted by the addition of Article 34 to the California Constitution, which mandates a local referendum be held before public funds can be committed to low-income housing. The issue thus complicated, the council dropped it. Public housing in Chico only reentered public dialogue through the efforts of groups like the League of Women Voters (LWV), First Christian Church and the Chico Grange. In 1956, the LWV initiated a study of zoning with regards to creating new housing.

The City Council soon after submitted a referendum to cooperate with the Butte County Housing Authority in the construction of 100 units of public housing. Like most public housing in the United States today, it would be low-rise and dispersed among different locales in the city. To assuage the concerns of local realtors—who had successfully tanked two public-housing referendums in the Oroville area in the previous years and organized a committee against this one—it was stipulated that within five years, at least as many housing units as are built would be demolished or renovated.

On November 4, 1958, the referendum passed with support from voters in every precinct in Chico. A series of luncheon meetings to detail the execution of the agreement took place afterward at Hotel Oaks, by many historical accounts a whites-only establishment and the tallest building in Chico before it was demolished for a parking lot.

Reinette Clark Porter, in her 1963 thesis for Chico State College on public housing in Butte County, recounts the meetings. The city government was fixated on ridding themselves of Daisy Lane by putting a portion of the new housing there, which the council believed was what motivated voters to support the referendum. The Housing Authority, however, loathed dealing with Daisy Lane’s many property owners and the slough running through, preferring instead to build in a field near the university. The city government was concerned about residents displaced from the demolition relocating near white and middle-class areas.

In the end, the city handled the slum-clearance part of the program, bulldozing Daisy Lane and filling in Dead Horse Slough with refuse from another effort, the Esplanade reconstruction project, which created the gorgeous gateway to the city’s northern frontier.

Because fewer than 12 of the residents of Daisy Lane were registered to vote, the city could push through annexation as an “uninhabited area,” bypassing the opportunity for them to contest the arrangement.

Public housing duplexes of identical design were set out in three additional sites in south Chico: La Leita Court, Natoma Court and the southern end of Hazel Street. The Hazel projects were built last and after some delay because, as Porter put it, “it was hoped that the [African-Americans] would move on rather than across town.”

If the people from Daisy Lane did stay in Chico, it’s likely they remained in the neighborhood. In a 1964 survey of the Black population, 77 percent of Black residents in the city lived in southeast Chico, primarily between Little Chico Creek and Boucher, California and Guill streets. Black people were found to commonly live in lower-quality housing than their white neighbors of the time, and of those who expressed dissatisfaction with where they lived, the most common factor cited limiting their relocation was their race. The study found that no Black people lived in northwest Chico and only four north of Bidwell Park.

The primary intent of the projects may have been to demolish undesired housing, but 60 years on, the cinderblock duplexes actually remain a successful endeavor, providing good quality housing for low-income residents.

Last year, when a resident of the Humboldt Avenue projects spoke to a local TV news outlet about frustrations with the homeless people living nearby, the newscast titled the story “Homeless vs Homeowners,” which in a way speaks to the dignity afforded to tenants of Chico’s public housing.

As far as those displaced to make way for the projects, while working on this story, the CN&R did encounter one Black resident of the Chapman neighborhood who remembered moving from Daisy Lane as a young child. But overall, we know no more than Porter did in 1963 when she wrote, “It has been impossible to determine what has happened to the other former Humboldt area residents, or exactly how many there were.”

Note on sources:

A thank you to the Special Collections department of Meriam Library at Chico State for providing images and materials cited in this article.

Interesting slice of history! Worth noting that the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) church is still just a couple short blocks from Humboldt Ave.,, at Linden and 9th street, and still serves as a hub for Chico’s black population.

I think this illustrates the concept of systematic racism well. To the author, thank you for this informative history of our community. Also please subscribe to CNR; this is the in depth journalism we m

Ritchie Lowry was a Professor at Chico State who also wrote a book about Chico called “Who’s Running this Town?” which is available in the Chico State library and Amazon. The name “Chico” does not appear–there is a pseudonym instead. Chapmantowo in the 1950s is described (pseudnymously) as well. https://www.amazon.com/Whos-running-this-town-leadership/dp/B0007DFDOS/ref=sr_1_3?crid=1DD3N1F3E1DKO&keywords=Ritchie+Lowry&qid=1655027791&sprefix=ritchie+lowry%2Caps%2C164&sr=8-3