CN&R file photo

Hundreds of supporters filled the Chico Masonic Family Center to hear presidential candidate Bernie Sanders unveil his climate plan.

PG&E under pressure

Following months of investigation, Cal Fire announced in May that it determined electrical transmission lines owned and operated by PG&E caused the Camp Fire. The blaze destroyed nearly 19,000 buildings in eastern Butte County and killed 85 people, becoming California's deadliest and most destructive wildfire.

The finding wasn't a surprise. The utility had informed regulators months earlier that it sustained a power failure where the Camp Fire started near Pulga on the morning of Nov. 8, 2018. Workers also found damaged equipment on a transmission tower in the area.

In January, PG&E filed for Chapter 11 reorganization in U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of California in anticipation of billions of dollars in wildfire liabilities. By June, the utility had reached agreements with local cities and counties totaling $1 billion. The payments included $252 million for the county of Butte and $270 million for the town of Paradise.

Then, earlier this month, PG&E announced it had amended its bankruptcy reorganization plan after reaching a $13.5 billion settlement to resolve all major wildfire claims stemming from the Camp Fire, as well as multiple Northern California wildfires in 2017. Gov. Gavin Newsom, however, has opposed PG&E's plan, saying it falls short of establishing a path toward providing safe, reliable and affordable service. He added that it also does not comply with Assembly Bill 1054, the state fund that's been established to pay for eligible wildfire claims.

PG&E has said it is aiming to emerge from bankruptcy by June 30, 2020, to take future advantage of the fund.

CN&R File Photo

Environmental activists honored victims of the Camp Fire and criticized PG&E during a meeting at Children’s Playground in Chico days before the fire’s first anniversary.

Newsom's wrench in the utility's bankruptcy plan followed his sharp criticism of PG&E's more frequent intentional blackouts on “red flag” days following the Camp Fire.

Meanwhile, the utility remains under criminal investigation by Butte County District Attorney Mike Ramsey, whose prosecutors have been viewing the body of evidence it has collected with two possible felony charges in mind: unlawfully causing a fire with gross negligence, and more than 80 counts of involuntary manslaughter.

The long identifying process

The state's deadliest and most destructive wildfire created a massive, challenging job for coroner's investigators over the past year: conclusively identifying the degraded remains of victims.

In July, about eight months after the Camp Fire ripped through eastern Butte County, six people remained unidentified.

Wally Sipher of Chico told the CN&R about the frustrating holdup in identifying his deceased sister, Judy, 68. She lived in Paradise and didn't flee her apartment as the fire barreled toward her. Sipher and his wife, Carol, knew Judy had perished, but the wait for the Sheriff's Office to officially identify her was agonizing (see “Vanished,” Cover story, July 25).

“We know she's gone, but it would be nice to have that noted for real,” Carol told the CN&R at the time. “And if they can't do it, they need to tell us that, too.”

CN&R file photo

Plastic water meters in Paradise did not withstand extreme heat during the Camp Fire.

Butte County Sheriff Kory Honea said the identification process was complicated by the intense heat of the fire. In some cases, victims were burned down to mere bone fragments, and efforts to identify their remains using DNA analysis had proved futile.

The DNA technology firm ANDE, which specializes in “rapid” DNA analysis, ultimately was hampered by the quality of the remains, said Richard Selden, the company's founder and chief scientific officer.

In August, the Sheriff's Office eventually turned to circumstantial evidence to identify Sipher's sister. Not long afterward, investigators released the names of the remaining victims for whom they had circumstantial evidence pointing to their identities.

Out of the 85 people killed in the fire, one person remains unidentified. The Sheriff's Office, after initially refusing to release information about the victim, said in September that he was a large, older man who had had dental work with crowns. His remains were found commingled with the remains of a woman, 72-year-old Ellen Walker, at a property in Concow.

Contamination conundrum

One of the many and arguably most difficult hurdles to overcome post-Camp Fire—at least on the Ridge—is the contamination found in the water conveyance systems.

After tests in January came back positive for unhealthy levels of the chemical compound benzene, which is known to cause cancer, the Paradise Irrigation System (PID) warned customers not drink water from the tap—or use it for brushing teeth, making ice or preparing food.

PID officials and plumbing experts brought in to help with the issue believe the contamination stems from plastic piping and meter boxes that melted during the blaze, leaching benzene into the water system. The lack of precedence, aside from the Tubbs Fire in Santa Rosa—which has a water system considerably different from Paradise's—made for a daunting task. In February, PID estimated it would take two to three years and cost hundreds of millions of dollars to fix the plumbing system.

Further complicating the issue is that the contamination existed not just in PID's infrastructure, but also in home plumbing that homeowners would need to test on their own. Moreover, unhealthy levels of “volatile organic compounds” also have been found in the system.

Thus began PID's complex effort to isolate and mitigate contaminated areas along 170 miles of pipe—either declaring portions clear of contamination or replacing the pipes. PID eventually determined that the contamination was mostly found in lateral plumbing lines—the pipe that goes from the main line to customers' meters.

Meanwhile, the Del Oro Water Co., which serves Magalia and its environs, also found unhealthy levels of benzene. However, the private company conducted simpler testing and told customers all along that its water was fine to drink.

As of November, PID had tested half of its distribution lines to standing structures—and cleared 38 percent of those. That same month, researchers from UC Davis announced preliminary results at a PID community meeting that showed minimal contamination within standing homes—some, however, had unsafe levels of chemicals from disinfection byproducts that required follow-up testing.

Progress and setbacks on homeless help

Two steps forward, then two steps back. That's an overarching theme of 2019 when it comes to addressing homelessness.

CN&R File Photo

Richard Muenzer was recently arrested while seeking a safe, dry place to sleep.

One of the highlights: In January, the Torres Community Shelter began operating 24/7, and secured enough grant funding to do so through June 2021. The day center concept marked a significant development, as local service providers historically have offered shelter only during late afternoon and evening hours.

In February, the city of Chico's new progressive City Council took an unprecedented step by setting up tents at Depot Park to create a warming center during a cold snap. The next month, the panel partnered with the Jesus Center, paying the nonprofit to operate warming and cooling centers the rest of the year. A “Code Blue,” city leaders initially decided, would be triggered when temperatures are predicted to fall below 32 degrees, and a “Code Red” would come into play when temperatures reach 100 degrees or higher for two or more days. In December, however, the council revisited the criteria for warming centers, expanding the scope. As of deadline, however, the Jesus Center's board of directors had not yet agreed to the new terms.

A significant motivation for the change: at least four people have been found dead on the streets of Chico this year. And a fifth, a well-known homeless man named Wilson “Grant” Tyler, suffered a health emergency at the City Plaza in June and died two days later at the hospital.

In terms of setbacks, two of them are attributed to NIMBYism.

After months of searching, Safe Space Winter Shelter and the Jesus Center announced in April plans to lease a building on Orange Street to open a 100- to 120-bed, 24/7 low-barrier shelter, buoyed by a $1 million grant from the Walmart Foundation. The project quickly fell apart, however. Public opposition swayed the Jesus Center to back out later that month. Then, in May, the North Valley Community Foundation returned the donation to the Walmart Foundation, which ultimately granted the lion's share of the funding—$850,000—to the Jesus Center, and the remainder to the Torres Shelter for its 24/7 operations. The Orange Street Shelter was no longer possible.

Another project long in the works will be hashed out in court. In September, the Chico Housing Action Team received final approval from the City Council to begin establishing its tiny home project, Simplicity Village, to create 33 tiny homes for about 45 seniors on Notre Dame Boulevard. But shortly thereafter, in November, Frank Solinsky, president of neighboring business Payless Building Supply, filed a lawsuit against the city and Brendan Vieg, its planning and housing director. The dispute comes down to land use: The city maintains that Simplicity Village is allowed temporarily and without a permit, per the shelter crisis declaration made last year. Solinsky argues that the project is permanent, and not allowed without a use permit and environmental review.

Meanwhile, the Renewal Center, the Jesus Center's proposed relocation/expansion project—including transitional and permanent housing, a day center and other services—is lagging. The council approved the sale of a 3.56-acre city-owned lot on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Parkway, the facility's proposed location, but the property still hasn't closed escrow. In November, the city extended the deadline to Dec. 2, 2020. According to a staff report, the unanticipated workload at the city post-Camp Fire has resulted in delays facilitating the relocation of the property's current lessee, Silver Dollar BMX, to a new location.

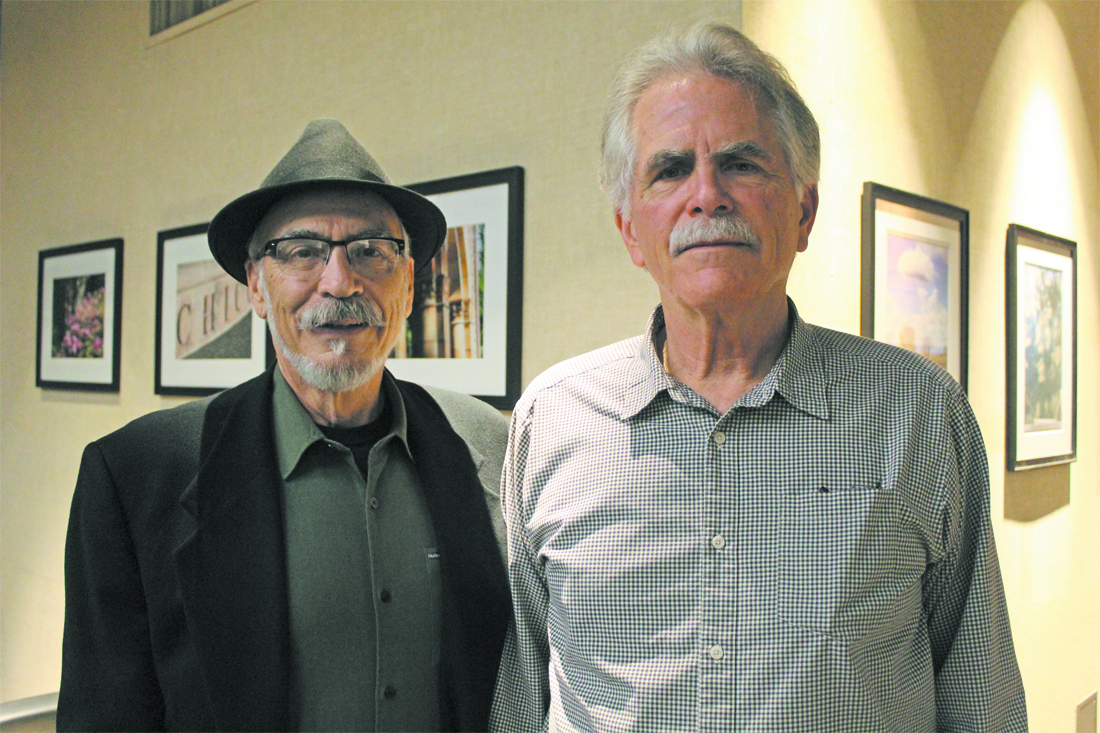

CN&R File Photo

Districts for Chico founders Ken Fleming (left) and Robert Speer started calling for district-based elections in 2015.

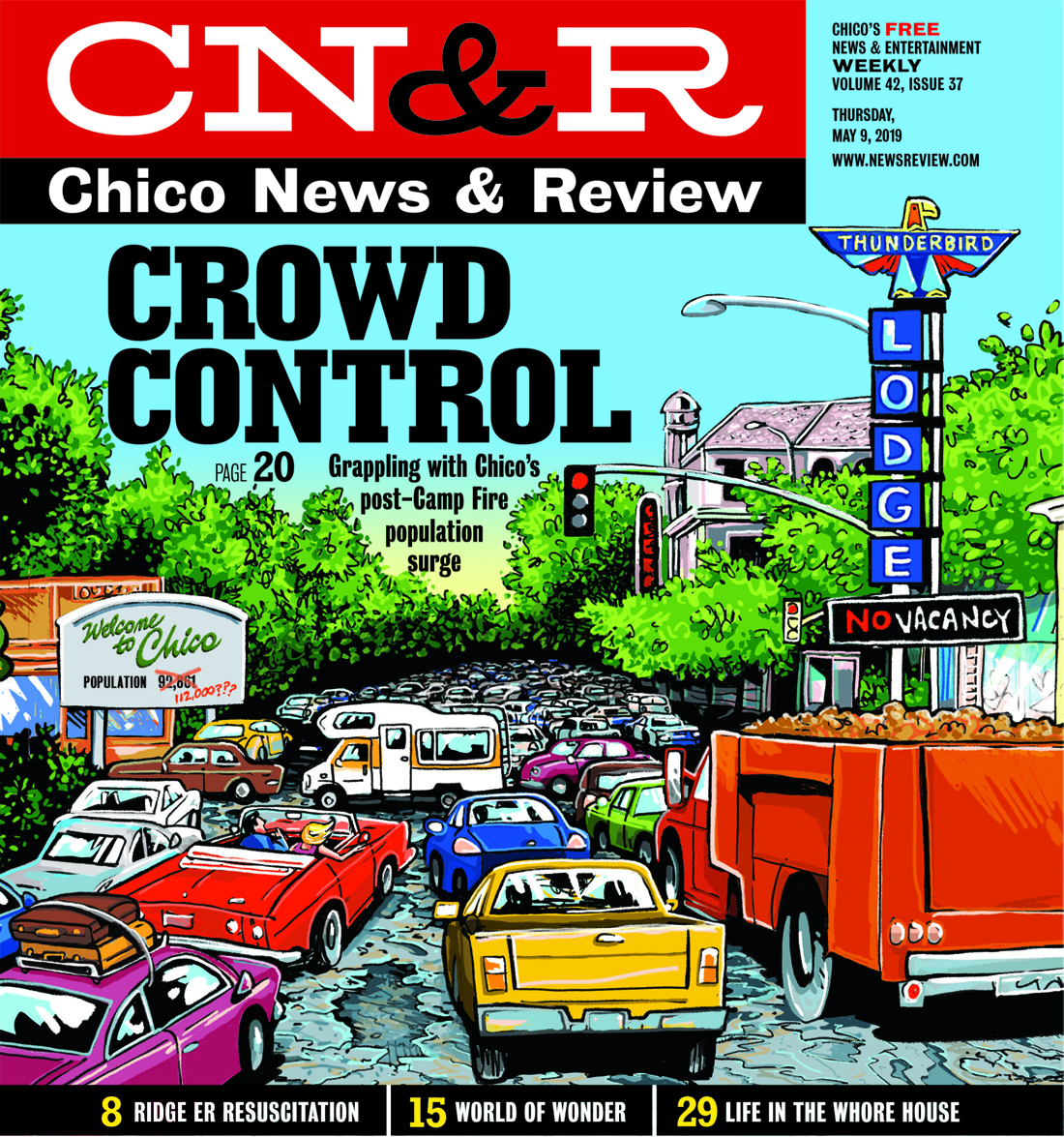

Unprecedented growth

Tens of thousands of residents displaced by the Camp Fire resettled in Chico and Oroville, immediately altering the municipalities' respective populations. But it became clear in 2019 that the surge wasn't temporary.

Early on, city leaders in Chico had estimated the increase at somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000 based on numerous factors, including a spike in traffic and sewer volumes. In early May, the state Department of Finance backed up the figures. Based on year-over-year analysis, Chico had gained more than 19,000 residents as of Jan. 1. That's a 20.7 percent increase. As the CN&R reported in a cover story at the time (see “Secondary effects,” May 9), under normal circumstances, the city would expect to see that level of growth in the 2030s. Oroville, meanwhile, experienced a 20.4 percent increase.

Among the services greatly strained in Chico as a result: public infrastructure (such as roads and sewer systems), public safety, refuse collection, medical care (see Healthlines, page 8) and housing supply.

Chico's average home price soared by more than $50,000 with the spike in demand. Looking to cash in on the post-disaster prices, landlords put their properties on the market. That created another wave of displaced residents—renters.

The unprecedented growth remains an ongoing challenge for Chico, but city leaders have taken several steps to address certain issues. An anti-price-gouging law that prohibits rent increases of more than 10 percent was instituted shortly after the fire and has been extended twice (it expires Dec. 31, 2020). Additionally, late summer and early fall, several City Council members organized a series of discussions related to the community's needs, including affordable housing.

One bright spot: The state allocated $3 million and $2 million to Chico and Oroville, respectively, for disaster relief. The funds come from a one-time state budget appropriation. In Chico, half of the funding was earmarked for public safety needs. City Manager Mark Orme called the allocation a “huge gift to this city and its citizens,” but noted that it was “a drop in the bucket of the actual impacts.”

Council drama

Chico progressives took control of the City Council toward the end of 2018, following four years in which conservatives held the majority. About five months later, in May, members of a community group and others filed paperwork aimed at recalling newly appointed Mayor Randall Stone and Councilman Karl Ory.

Gripes about how unsafe Chico had become was the rhetoric du jour. However, in June, Chico Police Chief Mike O'Brien put a damper on that narrative when he released a report revealing that crime had dropped during the first four months of the year when compared with the same time period in 2018.

Stone and Ory's detractors charged that the councilmen were wasting time on frivolous policies, including an ordinance to legalize commercial cannabis sales and efforts to address climate change.

In September, Councilman Sean Morgan made a request to reconsider Stone's appointment to mayor. Discussion of his motion revealed that some of Stone's progressive colleagues were less than enthusiastic with his leadership. In the end, though, he held onto the post.

Two months later, a few weeks before a deadline to submit 7,000 signatures, recall proponents threw in the towel. The purported reason: the city's expected move to district elections.

Interestingly, over at the county seat, the pendulum swung the opposite direction. The Oroville City Council transitioned from progressive to conservative and tossed out a plan to allow commercial cannabis. In May, the City of Gold's conservative mayor, newly elected Chuck Reynolds, found himself in hot water. Councilwomen Janet Goodson and Linda Draper filed a lawsuit against the council, alleging Reynolds violated the Brown Act and the city charter in March when he removed them from the committees on which they served without consent of the full council.

CN&R File Photo

Concow residents Teri and John Rubiolo in their large storage shed, where they keep food, toiletries and clothing to supplement the aid their neighbors receive at formal food pantries and donation centers.

In September, a reversal of sorts took place. Reynolds reinstated both Goodson and Draper on one of the committees from which they'd been pulled and the panel voted unanimously to confirm the appointments.

A new way to campaign

The two last months of 2019 spelled big changes for elections in Chico and Oroville. Both cities voted to move from an at-large system to district-based elections.

What that means is that voters will select City Council members from their district rather than from the entire bunch running citywide (although Oroville chose to continue electing its mayor at-large).

District boundaries have yet to be solidified for either city. They will be drafted and reviewed during an extensive public process in early 2020 to make the switch during the next general election.

The change didn't come voluntarily, nor did it come without consequences. Both cities were prompted to make the switch after they received letters from attorneys threatening a lawsuit, alleging a violation of the California Voting Rights Act of 2001 (CVRA). It prohibits the use of at-large elections if they impair the ability of minority populations to elect candidates or influence election outcomes, as the attorneys allege has happened in both Chico and Oroville.

Both cities determined that it wasn't a battle worth fighting: none of the other municipalities challenged in the state have successfully defended against such lawsuits, and several have shelled out millions of dollars in attorney's fees only to have to switch anyway (the CVRA requires losing jurisdictions to pay attorney's fees).

CN&R file photo

In May, Councilman Karl Ory, left, and Mayor Randall Stone were served with notices indicating a citizen effort to recall them from their seats on the Chico City Council.

In Chico, the kicker is that the city could have avoided the rush to switch had the council listened to members of Districts for Chico, who advocated for such a change back in 2015. The nonpartisan group argued that districts would create a more representative government that would improve efficiency and increase the chances of minority members and political independents getting elected. The topic was shot down then, and went nowhere when it resurfaced in 2018.

On top of that, both cities will end up paying to make the switch, as much as $30,000 in attorney's costs, as a result of being forced to comply with the CVRA. They'll also have to turn around and re-district when the 2020 census is completed.

Survivors struggle

More than a year has passed since the Camp Fire, but the struggle is nowhere near over for many whose lives were upended by the disaster. In 2019, it became clear that many survivors were still struggling to meet their basic needs, such as feeding themselves and their families and finding a stable home. Many are still living in cars and tents.

One of the prime examples: Though several neighborhoods have been established by the Federal Emergency Management Agency in 2019 to offer shelter to survivors—including one with 224 manufactured homes in Gridley and another with 73 homes in Chico—these developments are only temporary. In Gridley, for example, the federal government's deadline to vacate the space is May 2020. And in every neighborhood, FEMA employees perform monthly assessments of each household's efforts to secure permanent housing.

In a September cover story, Gridley FEMA community resident Jennifer Powell told the CN&R she had been searching for a new home for her and her boyfriend every day, and it had been impossible to find anything that was affordable (see “Home sweet temporary home,” Sept. 5). “We're stranded, like everybody else,” she said. “Everything is up in the air.”

Meanwhile, up on the Ridge, the Magalia Community Church became an epicenter for ongoing relief after opening the doors of its donation center in December of last year. It continues to serve thousands of fire survivors each month by providing clothes, furniture, toiletries and food. The latter is the most pressing need, even now. The center, which runs entirely on donations, recently received some good news: It was awarded $102,000 by the Butte Strong Fund to help continue its operations for another six months.

CN&R File Photo

Jenna Murray (left) and Kyla Awalt launched the Camp Fire Zone Project in March to help the Ridge rebuild and stay connected.

Relief efforts have been ongoing in outlying Ridge areas as well. In Concow, for example, couple Teri and John Rubiolo—who also lost their home in the blaze—have focused on helping their neighbors. They make and serve dinner for 35 to 50 people three days a week (something they started before the fire), and another three days a week they make deliveries, reaching 90 to 120 people per month. They arrive bearing donations of everything from canned goods, shampoo and clothing to generators, cars and trailers.

Recovery progress

Though recovery on the Ridge has been slow going in many respects, Butte County also made significant progress in 2019. That includes completion of the state's debris removal program in November, an effort that cleared nearly 11,000 lots of more than 3.6 million tons of debris.

Meanwhile, few homes in the region have been constructed. As of this month, 216 people have applied to rebuild their homes in unincorporated Butte County, but only 123 permits have been issued and only eight homes are in the “final” stage or “may be occupied,” according to Butte County. In Paradise, 24 homes have been rebuilt and 604 applications have been received.

Though the county and town have worked to streamline barriers to development, those seeking to rebuild or continue to live on the Ridge have been faced with unexpected price tags, such as permits for generators needed to power their trailers or homes during PG&E power safety shut-offs. Additionally, homeowners living in high-fire risk areas have found that their home insurance policies are not being renewed or have become unaffordable—in some instances spiking more than 250 percent.

In the education realm, significant efforts to repopulate the Ridge have forged onward. Paradise Unified School District's students returned to Ridge campuses for the fall 2019 semester. Because of the destruction, however, some campuses were combined or relocated. As of October, the district had about 1,700 students, compared with its pre-fire count of approximately 3,380.

Meanwhile, other initiatives launched to encourage the repopulation have been greatly received. This includes the Camp Fire Zone Project. The group, founded in March by two survivors, encompasses 33 zones in the burn scar, with volunteer leaders in each serving as an informational resource, neighborhood event planner and government liaison.

State legislators also worked on policies to help survivors recover and rebuild.

In October, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Sen. Jim Nielsen's Senate Bill 156 into law, allowing Adventist Health Feather River to open a standalone emergency room. The health care provider committed to reopening one at its existing main campus on Pentz Road, which was damaged in the fire.

Also in October, Newsom signed Assemblyman James Gallagher's Assembly Bill 430, which circumvents certain California Environmental Quality Act mandates to streamline residential development in Biggs, Gridley, Corning, Live Oak, Orland, Oroville, Willows and Yuba City (Chico chose to opt out).