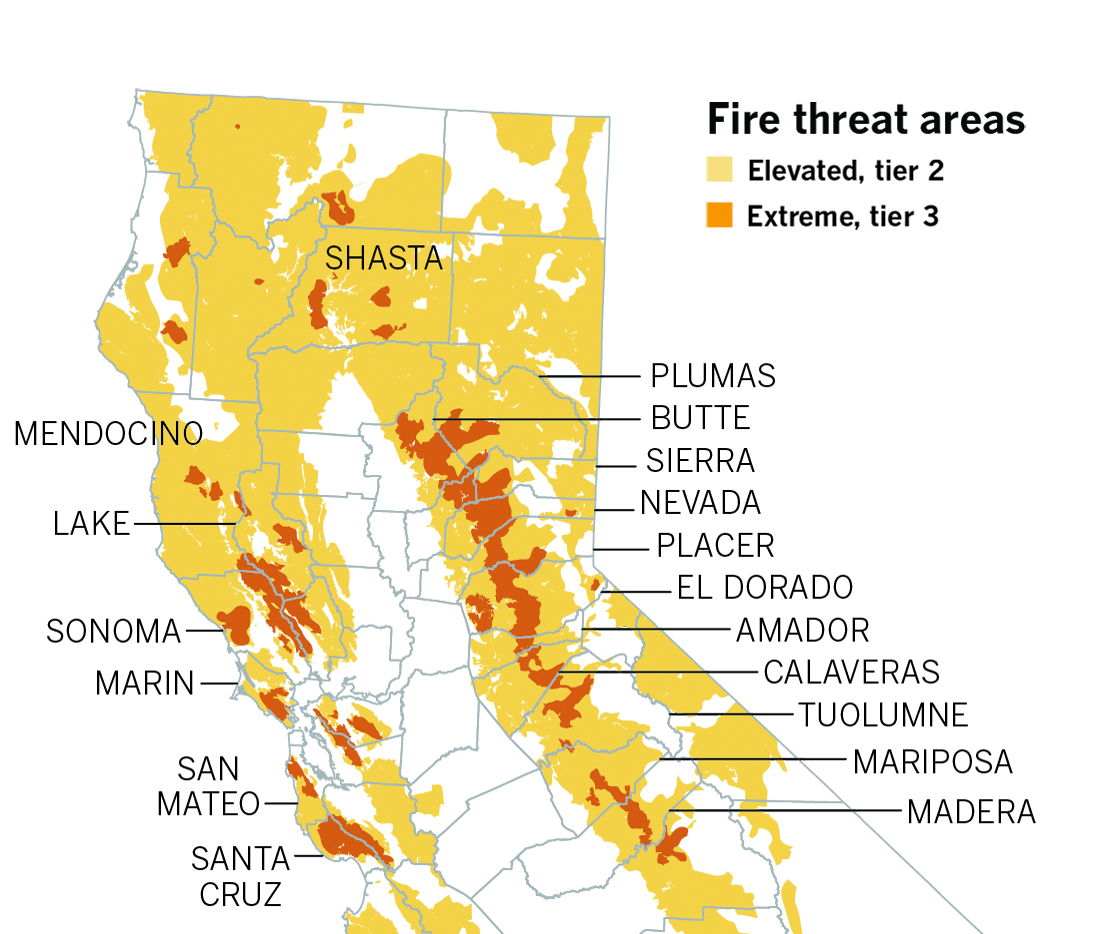

Map courtesy of California Public Utilities

Map shows counties most vunerable to wildfires in Northern California.

The city of Winters is a cluster of old Italianate façades and worn Western storefronts tucked between Putah Creek and a dry, sweeping expanse of the Vaca Mountains. Over the years, the ranchers and farming families who live here have weathered drought, disease and at least one devastating earthquake.

It takes a hardy mindset to keep the hamlet thriving. It survives mainly on the whims of the beef industry and the health of its endless tracts of almonds and walnuts. Most residents are self-reliant. So when homesteads beyond the city’s outskirts were hit with a complete blackout June 7, Yolo County’s Office of Emergency Services wasn’t flooded with worried calls.

That’s partly because Winters residents don’t fluster easily, but it’s also because county officials prepared for this moment for nearly a year. The outage was only the second time ever that Pacific Gas & Electric Co. activated its Public Safety Power Shutoff program. The controversial initiative is aimed at stopping catastrophic wildfires before they start by flagging a combination of dry conditions, high winds and low humidity—and then de-energizing entire sections of the power grid in those areas.

PG&E equipment has been blamed for sparking hundreds of wildfires in California, including last November’s Camp Fire—the deadliest and most destructive in the state’s history—that killed 86 people, burned more than 150,000 acres and all but wiped out the town of Paradise. The estimated $30 billion in claims from those fires forced the utility giant to file for bankruptcy protection in January.

PG&E first rolled out the safety program in October 2018 by shutting off power to 60,000 customers in seven counties. The utility soon heard from irate customers, bewildered officials and frustrated emergency responders. The unexpected power-down cost local economies tens of thousands of dollars in lost wages and revenues. Phone lines, cell towers and the internet went dark for days in some rural neighborhoods. By PG&E’s own admission, hundreds, if not thousands, of medical “baseline” customers—people who depend on oxygen tanks, respirators and nebulizers—were left vulnerable. The question of how many isolated seniors and disabled citizens couldn’t call family members or 911 led to a hearing at the California Public Utilities Commission.

But on June 7, Yolo County officials were determined to have a better result.

“There was a lot of difference from last year,” said Dana Carey, manager of the Yolo County Office of Emergency Services.

This time, Carey’s team had information on where all of PG&E’s medical baseline customers lived. For months they’d been combining that data with their own information on at-risk residents, creating a digital mapping system that sheriff’s deputies and firefighters could use in real time. When Yolo County authorities learned PG&E would cut the power near Winters, they sent alerts through voice calls, text messages, phone apps and a special communication system for the hearing impaired. First responders also were ready to conduct welfare checks on anyone there was a concern about.

Not all Northern California counties are working as hard as Yolo to deal with future PG&E power shutoffs. But experts say they should be.

Even though PG&E provides power to much of the state’s $2.7 trillion economy, the company is fighting for its very survival. If the investor-owned, for-profit utility manages to emerge from bankruptcy, it still will face a chorus of calls for the company to be split up or taken over by the state.

Further muddling the picture, clean energy advocates are worried that only a company of PG&E’s size and scope can push California to reaching its ambitious climate change goals, in part to stave off global warming that’s already exacerbating the state’s wildfire season.

The power shutoff program is one of PG&E’s main strategies to stay in business. But how will it manage its new task of constantly making decisions about when and where people can have electricity—and sometimes, life and death?

Throwing the big switch

After PG&E triggered its first safety shutoff in the fall of 2018, a line of stunned residents flooded the El Dorado County supervisors’ chambers to describe near-miss scenarios in which infirm, isolated seniors might have experienced medical crises with no way to call for help.

Photo courtesy of PG&E

PG&E monitors conditions for potential wildfires in Northern California from a command center in San Francisco.

But PG&E managers appeared at the same meeting to describe a different close call that happened during the shutoff: High winds flung a tree into a power line in a rural corner of Amador County. If the system hadn’t been de-energized, a blaze could have been sparked, sweeping through the towns of Pioneer, Pine Grove and Volcano, where more than 5,000 live around dry, dense forest. PG&E manager Aaron Johnson called that a “data point” to prove the new program works.

Similar evidence emerged during the June outage. PG&E’s team of meteorologists initiated power shutoffs in three different regions: The farms and ranches outside of Winters, a much larger swath of terrain across Butte and Yuba counties and areas of El Dorado, Nevada and Placer counties. While only 1,500 customers living near Winters were affected, some 26,900 customers lost power in the other regions. According to a report PG&E filed with the state utilities commission, prior to bringing the grid back online, its inspection teams found five spots where fires could have started, including three in Butte County, a place already brought to its knees by the Camp Fire.

There, the company’s inspectors discovered a wind-split tree that had fallen into a PG&E structure cable and service drop in Oroville, as well as two different power lines that had been hit by flying branches in Chico.

“In each case, PG&E repaired or replaced the damaged equipment prior to re-energizing,” the company told the state. “In addition to these damaged assets, PG&E personnel discovered three instances of documented hazards, all vegetation-related, such as branches found lying across conductors, which were cleared.”

Ironically, on Nov. 6, 2018, PG&E’s Wildfire Safety Division had issued a media alert stating that dangerous fire conditions were being predicted by its threat matrix for Butte County. If they continued, the company said then, it likely would initiate a power shutoff. Though its officials were still monitoring high winds and low humidity around the town of Paradise, they never cut off the power. In May, state fire investigators announced that one of the two ignition points for the Camp Fire was a PG&E power line.

The contrast between decisions PG&E’s management team made in Butte County in 2018 and 2019 shows just how much control they potentially have over life, property and a community’s livelihood.

That’s a level of responsibility to which PG&E is trying to adjust.

Thirty-six hours before the June safety shutoff, PG&E warned sheriff’s offices, fire stations and county emergency departments that it was about to happen. Unlike 2018, the utility says any counties that signed a nondisclosure agreement now have access to its list of a medical baseline customers who depend on power-run medical equipment.

Yolo and Butte counties had that information in June. Placer and Yuba counties did not, because their attorneys and elected officials were still reviewing the details of the nondisclosure agreement. El Dorado County declined to answer whether it had signed the NDA.

PG&E spokesman Jeff Smith said that, regardless of which counties are using the medical baseline list, PG&E has its own protocol to warn those customers and make sure they have a safe place to go that still has power.

“Medical baseline customers are our highest priority when we’re calling for one of these events,” Smith said. “If we’re not reaching them by phone, then we’ll actually dispatch a team to go out and make contact.”

But Smith also noted that PG&E’s medical baseline list is part of a voluntary program where customers with health issues can sign up for savings on their bills. That means there could be a lot of people who are medically vulnerable who aren’t currently known to PG&E or county emergency response officials.

“What the medical baseline list is not is a panacea of knowing every customer that has a medical issue,” Smith acknowledged. “It is the best tool we have, but it doesn’t tell us everything. Anyone with a medical issue who relies on power needs to get a hold of us.”

The Utility Reform Network, a San Francisco-based organization that’s one of PG&E’s loudest critics, has expressed skepticism of the safety shutoff program. It told the San Francisco Chronicle in May that the corporation’s messaging around the initiative indicates it could be used too often—and thus put too many vulnerable people at risk.

Smith says that PG&E isn’t taking the power outages lightly, but admitted it can be “a double-edge sword” with unintended consequences.

Photo by Melissa Daugherty

PG&E crews work along Clark Road in Paradise on Nov. 9, the day after the Camp Fire began.

For county officials such as Carey, who has worked to not only lessen the impacts of the shutoffs but also to provide residents real-time digital maps of spreading fires and open escape routes, PG&E’s program is part of how a hotter, drier California is confronting all emergency agencies.

“We were already doing a lot of work before the blackouts started,” Carey said. “The fact is, we’ve burned five out of five years in our county.”

Price and power of monopoly

It has not been a quiet year at the California Public Utilities Commission. Since the Camp Fire, enraged protesters have shown up at meetings to demand PG&E be dismantled as a for-profit corporation. These critics have been quick to remind commissioners that a San Francisco jury in 2017 found PG&E guilty of six felonies linked to the 2010 San Bruno gas pipe explosion, which killed eight people and convinced a judge to put the utility on federal, court-monitored probation.

“I think the working people of California are fed up with the continued death and destruction caused by the utilities, by PG&E,” Steve Zeltzer of United Public Workers for Action told commissioners in November. “The utility executives should be in jail for what they’ve done. They’ve lied to the people of California …. And the utility should be a public utility. Take the profits out of utilities. The public should control it, not these profiteers who don’t give a damn about what they’ve done.”

To some extent, that message was heard. A month later, the commission started the formal process of reviewing whether PG&E should be broken up into regional subsidiaries or restructured as a state-owned company. While that review continues, the city of San Francisco is separately exploring whether it can take over control of PG&E’s power distribution within its limits. PG&E has publicly warned that any forced restructuring likely would result in higher utility bills for the average Californian.

Frank Gevurtz, a professor at McGeorge School of Law in Sacramento who specializes in antitrust litigation, says the company is probably correct in that assumption. Gevurtz also notes that while PG&E is a for-profit entity under its state corporate structure, it also falls into what California law defines as “a natural monopoly.” He explains that, throughout U.S. history, natural monopolies have been allowed when it’s not economically or practically efficient to have different or overlapping service infrastructure. For example, major telephone companies once were natural monopolies. Some railroad companies still are.

“In PG&E’s case, it’s not feasible for multiple companies to have duplicate power and gas lines,” Gevurtz said. For that reason, the professor is skeptical that ratepayers would benefit from a state takeover or major restructuring of PG&E since the transmission grids would remain unchanged.

“You won’t accomplish anything to break the company up into pieces,” Gevurtz said. “You won’t have different electric lines in the same place. It doesn’t create competition. If you’re a natural monopoly, you’re a natural monopoly.”

And PG&E’s status as a monopoly has created another major concern within California’s environmental movement, one that ultimately might help maintain its status quo. PG&E currently has contracts to buy roughly $42 billion worth of clean energy from wind and solar providers over the next 20 years. It also has made an estimated $1.7 billion in additional investments in other clean energy initiatives. Finally, PG&E is the main player in the plan to take the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant near San Luis Obispo offline by 2025 and replace it with zero-carbon energy sources.

In other words, PG&E is not only capable of taking major steps to combat climate change, it also has already been willing to do so. If the utility is broken up, environmental advocates worry that would be a significant setback.

“The utility companies continue to be essential partners in the clean energy programs that California has pioneered for the country and the world, and PG&E has been the largest partner in that effort,” said Ralph Cavanagh, energy program co-director with the Natural Resources Defense Council. “If you’re someone who is worried about the direction of clean energy, it’s certainly not obvious that breaking PG&E up would help.

“There are certain advantages to scale,” he added. “If you look at California’s record in driving down the cost of clean energy, companies like PG&E were a big part of that.”

The deadline for PG&E to emerge from bankruptcy is June 2020. It’s expected to present its plan for doing that next month. Cavanagh said that if PG&E can successfully do so, it would constitute the clearest path for the company to begin compensating wildfire victims, qualify for the state’s new fire emergency fund and keep its own herculean environmental commitments on track.

This potential outcome could determine its future, along with PG&E’s new initiatives such as the safety shutoff program, its satellite fire detection and alerting system, its expanded weather stations and vegetation clearing efforts.

“PG&E has turned to a radical approach on wildfire safety now, and I think we have to let them try it and give them a chance to see if it can be done,” Cavanagh said. “And I think we need to remember that whether you’re a wildfire victim or a clean energy advocate, as long as PG&E is in bankruptcy, nobody’s hopes and dreams can be realized.”